Perhaps the most telling insight into the nature of Flemish narrative painting comes from one of the genre’s most severe critics, Sir Joshua Reynolds. In his Journal to Flanders and Holland (1781), he makes the following charges:

“[Dutch and Flemish painters show people] engaged in their own peculiar occupations; working or drinking, playing or fighting.”

For Reynolds, there is no proper narrative in such works: only representation, without any dimension of civic or moral virtue to improve the viewers’ understanding of the world.

Important people and important events, he implies, are the only worthy subjects of art.

But for some painters — from Bruegel to Norman Rockwell — it is just those situations of everyday life that give us insights into the nature of human society. The sacrifice of Christ or the heroism of George Washington are, in the grand scale of human events, supremely important. But most of us lead our lives working, partying, paying taxes and playing music. Even in the midst of profoundly important events, such as Christ’s procession to the Calvary, each person in the crowd has his or her own personal concerns, and may or may not care about, or even be aware of, the big-picture event that encompasses them.

Such everyday responses to life comprise what the Flemish (and other) painters excel at: “the human condition.”

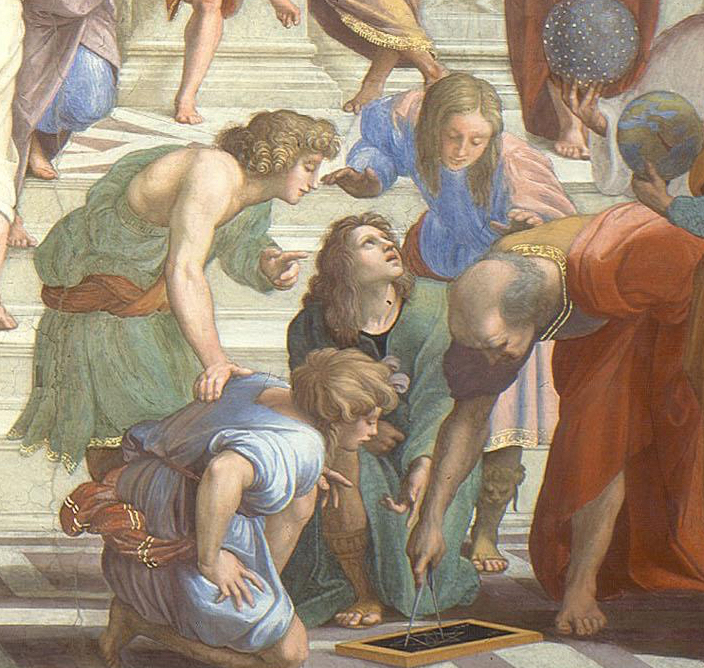

Click the image or text below for a full view and discussion