RAMBLES

Being a collection of brief commentaries and improvisations on themes from Samuel Johnson’ Rambler

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1) Introduction and first post: Unattainable Perfection (Rambler # 134)

2) Hope (Rambler # 3)

3) Refuse to be Pleased (Rambler # 2)

4) The Fruit of Flowers (Rambler # 5)

5) Mastery (Rambler # 8)

6) Hypocrisy (Rambler # 14)

7) Virtue and Habit (Rambler # 28)

8) Advice (Rambler # 40)

9) An Original Rambler (Rambler # 113)

10) Preserved So Long (Rambler # 45)

11) Life Lessons (Rambler # 50)

12) Johnson Censured (Rambler # 57)

13) Firmness and Industry (Rambler # 182

14) Our Own Importance (Rambler # 159)

15) Secretary of the London Garret (Rambler # 161)

16) Antiquarian Paradise (Rambler # 161)

17) Wish Fulfillment (Rambler # 163)

18) Rashness and Cowardice (Rambler # 1 and # 25)

19) Lessons from the Library (Rambler # 2)

20) Reason (Rambler # 162)

21) Ruined Reputation (Rambler # 207)

22) Rewards (Rambler # 131)

23) Social Virtue (Rambler # 44)

24) Resentment (Rambler # 185)

25) Virtue and Courage (Rambler #185)

26) Money and Happiness (Rambler # 189)

27) Encountering Evils (Rambler # 134)

28) Mistrust (Rambler # 79)

29) Sorrow and Employment (Rambler # 47)

30) Desisting (Rambler #208)

Last time my wife and I were in London, we stopped into The Cheshire Cheese, a wonderful pub frequented by Dr. Johnson, and not too far from his house. I imagined what it would have been like to sit at a table across from “The Great Cham” and listen to him discourse on such topics as drew his attention, always explicating the appropriate moral lesson as he does in his Rambler.

"Dr. Johnson at the Cheshire Cheese, Fleet Street" by Frank Moss Bennett

For some time now, I have started every morning by reading one of the Rambler essays. When I’ve finished them all, I go back to the beginning and start over, always finding something familiar and something new. And even apart from the thought-content of those pieces, I always enjoy the strong, clear music of his prose .

Pure wine, as Dr. Johnson himself referred to his Rambler. Or perhaps Bach’s genius for musical invention rendered in prose.

I am the list owner of the Yahoo group dedicated to Johnson’s works and life. Recently, however, there has been very little activity on the list. So I decided, in imitation of Johnson’s schedule for the Rambler, to post my own rambling comments on the thoughts he expressed.

#1: Unattainable Perfection

“He that has abilities to conceive perfection, will not easily be content without it; and since perfection cannot be reached, will lose the opportunity of doing well in the vain hope of unattainable excellence.” (Rambler #134)

I wish I had taken Dr. Johnson’s words to heart while I was struggling with my doctoral dissertation. I could not complete it until I realized that the goal of such a project is not to discover and display final Truths, but rather to finish the project and move on to the next task.

I did learn the lesson and was able to apply it, within the limitations of my abilities, to complete a number or writing and web projects over the years. I’m particularly satisfied with my essays on the nineteen industrial expositions held in Paris — national and international — between 1798 and 1937. They took a long time to reseach, and even longer to complete. But, thanks to Dr. Johnson, I was able to comfort myself with the satisfaction of a job done to the best of my abilities, though of course far from perfection.

Here’s a list, with links, to my writing and web publishing over the years.

#2: Hope

The natural flights of the human mind are not from pleasure to pleasure, but from hope to hope. (Rambler #2)

For some time, philosophers and psychologists have asserted that the “pleasure principle” rules human behavior. The two most sought-after human activities — eating and procreation — certainly have a high, and maybe even the highest, concentration of physical plaesure of any.

But Johnson reminds us that the imagination can produce an even more fundamental flight in pursuit of pleasure: hope, which the dictionary defines as “cherishing a desire with anticipation.” Its rewards are not the kind of intense physical pleasure of the moment. But as a fervent longing, or even just a strongly yearned-for fantasy, hope can carry our imagination into “boundless futurities.” However, the longings of hope do not always carry us to fulfillment:

Where, then, shall hope and fear their object find?

Hope, like Eurydice, often fades and recedes once we try to possess her. Hope, as a flight, can lead us on without ever granting us the fulfillment of the primary physical passions.

Finally, hear two later writers on the unintended consequences of fulfilled hope:

“There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.” — Oscar Wilde

“More tears were shed over prayers that were granted than ever were shed over prayers that were refused.” — Patrick O’Brian

#3: Refuse to be Pleased

Phillipe Faraut, "The Art Critic" (2008)

The ignorant always imagine themselves giving some proof of delicacy, when they refuse to be pleased. (Rambler #2)

In our times, online reviews can be found for virtually every product or service open for purchase and enjoyment. Amazon and Yelp reviews exist in huge numbers: 121 million for Yelp in 2016 alone, 11 billion for amazon over thirteen-year period. It is no surprise, then, to find many negative reviews online, many of which reveal little more than the author’s refusal to be pleased: a delay in restaurant service, medicine that did not provide instant relief, films that failed to live up to the high standards of the reviewer. With our easy access to sites that will publish any and all reviews, criticism has become democratized in our era, mostly with useful results, but occasionally providing platforms for allowing self-appointed critics to vent their dislikes and advertising their “proof of delicacy.”

Johnson writes feelingly about such self-appointed judges:

Little does the critic think... how many honest minds he debars from pleasure, by exciting an artificial fastidiousness, and making them too wise to concur with their own sensations.

And again:

Censure is willingly indulged because it always implies some superiority.

They [critics] have presumed upon a forged commission, styled themselves the ministers of Criticism, without any authentic evidence of delegation, and uttered their own determinations as the decrees of a higher judicature.

At times, even a “standard of perfection” can “vitiate the temper”:

It sometimes happens that too close an attention to minute exactness, or a too rigorous habit of examining every thing by the standard of perfection, vitiates the temper, rather than improves the understanding, and teaches the mind to discern faults with unhappy penetration.

In some cases, Johnson traces negative criticism back to the sin of envy:

Envy is mere unmixed and genuine evil; it pursues a hateful end by despicable means, and desires not so much its own happiness as another’s misery.

And even a kind of intellectual sadism:

The genius, even when he endeavours only to entertain or instruct, yet suffers persecution from innumerable critics whose acrimony is excited merely by the pain of seeing others pleased, and of hearing applauses which another enjoys.

During the years of the Rambler’s publication, Johnson himself often pronounced negative appraisals, not merely of hack writers, but upon the likes of Shakespeare and Milton. But in the Rambler, such criticisms of society and poetry are always rendered in the spirit of “literary criticism” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literary_criticism): observations made, not for gratifying his ego or persuading us that he possesses superior understanding, but to open up the nature and design of human endeavors to his reading public. This “criticism” would have, as its focus, not the ego of the critic, but the nature of the works under examination and the improvement of the readers’ minds.

#4: The Fruit of Flowers

A blighted spring makes a barren year, and that the vernal flowers, however beautiful and gay, are only intended by nature aspreparatives to autumnal fruits. (Rambler #5)

In the United States these days, media reporters are on the trail of the latest hot topic: sexual harrassment. Celebrities, politicians, and other prominent folk are, of course, given front page status, though no one doubts the existence of vast numbers of similar cases beneath the notice of the news people.

Hunger and sexual desire, the urge to survive and procreate, are the two most deep-seated, species-prevalent, and strongest urges for all living creatures. With hunger, the passion to eat seems about the same for both sexes. But the strategies for attracting and acquiring a mate are clearly markedly different, especially so in first-world countries, where sexual activity can easily be separated from childbirth, and the pleasure of the act can be enjoyed without the future biological consequences of bringing children into the world.

For many males, a position of power over an attractive female (or male) exerts a very strong inducement to use that power to gain sexual access to the subordinate. Each member of both sexes has a personal stock of approach and avoidance strategies for acquiring or repelling a potential mate. But now, in addition to the personal embarrassment and frustration of rejection, the unsuccessful male faces the very real possibility of public exposure and legal retaliation. Nevertheless, the randy male too often continues his pursuit, with the accompanying spiritual decline so aptly observed by Johnson:

Our senses, our appetites, and our passions, are our lawful and faithful guides, in most things that relate solely to this life; and, therefore, by the hourly necessity of consulting them, we gradually sink into an implicit submission, and habitual confidence. Every act of compliance with their motions facilitates a second compliance, every new step towards depravity is made with less reluctance than the former, and thus the descent to life merely sensual is perpetually accelerated. (#7)

#5: Mastery

It is said by modern philosophers, that not only the great globes of matter are thinly scattered through the universe, but the hardest bodies are so porous, that, if all matter were compressed to perfect solidity, it might be contained in a cube of a few feet. In like manner, if all the employments of life were crowded into the time which it really occupied, perhaps a few weeks, days, or hours, would be sufficient for its accomplishment, so far as the mind was engaged in the performance. For such is the inequality of our corporeal to our intellectual faculties, that we contrive in minutes what we execute in years, and the soul often stands an idle spectator of of the labour of the hands, and expedition of the feet. (Rambler #8)

Essayist Malcolm Gladwell once wrote that to achieve mastery in any endeavor requires about 10,000 hours of practice (he sites examples from computer programming and music).And, as someone else (Eddie Van Halen?) remarked: “It’s not how many years you’ve been playing the guitar that counts: it’s the number of hours.”

Continuous, concentrated effort is what matters. As with Aristotle’s observations that “moral virtue comes about as a result of habit,” so an effective approach to mastery requires consistency and continuity. However, it seems to me that, in the efforts to achieve mastery, the soul must not stand idle while the labor of the body does its work. The body can indeed learn, by “muscle memory” while the mind wanders. But the learning is not optimal. Souls should not stand idly by: they should provide direction, determination, criticism and encouragement.

#6: Hypocrisy

Nothing is more unjust, however common, than to charge with hypocrisy him that expresses zeal for those virtues which he neglects to practise; since he may be sincerely convinced of the advantages of conquering his passions, without having yet obtained the victory, as a man may be confident of the advantages of a voyage, or a journey, without having courage or industry to undertake it, and may honestly recommend to others, those attempts which he neglects himself. (Rambler #14)

In the above quotation, Doctor Johnson penned what must be the most powerful defense of a despised practice: saying one thing, thinking another, using flattery to disguise dislike, professing rectitude while practicing evil.

Johnson himself realized, in a later Rambler, that theory out of sync with practice lacks attractions to those who know both manifestations of a person who says one thing and does another:

The teacher gains few proselytes by instruction which his own behaviour contradicts; and young men miss the benefit of counsel, because they are not very ready to believe that those who fell below them in practice, can much excel them in theory. (#50)

Other writers have occasionally given a semi-humorous spin:

La Rochefoucauld, Maxims: “Hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue.” (L'hypocrisie est un hommage que le vice rend à la vertu.)

And from Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary: “Politeness, noun: The most acceptable hypocrisy.”

It seems unusual that Doctor Johnson, so strict an observer of rectitude and honesty, should go out of his way to defend hypocrites. But compassion is another of his personality traits, and perhaps that sympathetic understanding allows him to see the virtue inside the vice.

#7: Virtue and Habit

One sophism by which men persuade themselves that they have those virtues which they really want, is formed by the substitution of single acts for habits. A miser who once relieved a friend from the danger of a prison, suffers his imagination to dwell for ever upon his own heroic generosity; he yields his heart up to indignation at those who are blind to merit, or insensible to misery, and who can please themselves with the enjoyment of that wealth, which they never permit others to partake. From any censures of the world, or reproaches of his conscience, he has an appeal to action and to knowledge: and though his whole life is a course of rapacity and avarice, he concludes himself to be tender and liberal, because he has once performed an act of liberality and tenderness. (Rambler #28)

In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle states the principle that “moral virtue comes about as a result of habit.” The principle might be extended to any activity in which steady progress comes not from sporadic bursts of activity, but from steady application of will to what the mind has undertaken to accomplish.

Habit does not have to come from a set timetable like tithing at church. But the habit does have to come about as a choice of free will. Military exercises and prison routines enforce regularity, but they do not, of themselves, inculcate “moral virtue.”

For a functional understanding of morality, minus its theological connotations, we might take as a guideline this definition: “Morality is concerned with the prevention, alleviation, or cure of suffering.” As a principle, to incorporate the judgments of Johnson and Aristotle, we must add that true charity consists of a committed resolve to prevent, alleviate, or cure suffering.

#8: Advice

It is decreed by Providence, that nothing truly valuable shall be obtained in our present state, but with difficulty and danger. He that hopes for that advantage which is to be gained from unrestrained communication, must sometimes hazard, by unpleasing truths, that friendship which he aspires to merit. The chief rule to be observed in the exercise of this dangerous office, is to preserve it pure from all mixture of interest or vanity; to forbear admonition or reproof, when our consciences tell us that they are incited, not by the hopes of reforming reforming faults, but the desire of shewing our discernment, or gratifying our own pride by the mortification of another. It is not indeed certain, that the most refined caution will find a proper time for bringing a man to the knowledge of his own failings, or the most zealous benevolence reconcile him to that judgment, by which they are detected; but he who endeavours only the happiness of him whom he reproves, will always have either the satisfaction of obtaining or deserving kindness; if he succeeds, he benefits his friend, and if he fails, he has at least the consciousness that he suffers for only doing well. (Rambler #40)

The first condition is rendering advice, from whatever motives, should be that the person concerned should ask for advice. The proferring of unsolicited guidance always runs the risk of “the desire of shewing our discernment, or gratifying our own pride by the mortification of another.”

In the world of addiction and codependency, people who are trying to help other people rid themselves of their dependence often fall into “an excessive and unhealthy tendency to rescue and take responsibility for other people.” The two cardinal rules for guiding people out of codependency are:

You can’t control someone else’s life;

and, to the point raised by Johnson’s essay

Don’t give advice unless it’s asked for.

When we see someone we care about making bad decisions, there is an immediate urge, with the best of moitives, to violate both of those principles. It make no difference that out intentions are honorable, and the advice sound. the intervention, if not solicited by the person in difficulties. If the sufferers really wants help, they will ask for it.

#9: An Original Rambler

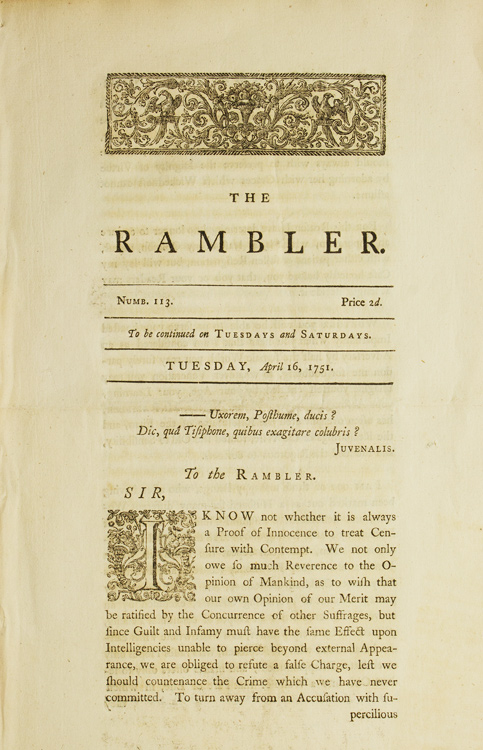

A while back I was looking for an online image of the original Rambler publication. Soon I turned up this:

It turned out that the image was posted by a book dealer offering the issue for sale. So I splurged and bought it. This morning, I carefully removed my new/old Rambler from its protective case and read it through. It’s been a long time since I read an eighteenth century book, with its curious long s script, placing the first word of the next page at the bottom of the current one, etc. I was also surprised that my original Rambler had no translation underneath the Juvenal quotation at the beginning (my digital version includes a translation by Dryden).

In the past, I had highlighted this passage from Rambler #113:

Beauty, Mr. Rambler, has often overpowered the resolutions of the firm, and the reasonings of the wise, roused the old to sensibility, and subdued the rigorous to softness.

Few people, I believe, would dispute that observation, made by the fictional letter-writer whose unsuccessful dealings with “the fair sex” constitute the story of this issue. What the passage invites us to reflect on is the mystery of how and why beauty exerts such power over such a variety of temperaments and ages. Perhaps the idea of “charm” might provide a clue, by ascribing the power of beauty to a kind of occult attraction not bound by the ordinary rules of physical or mental operations.

However, in this issue of the Rambler,the force of beauty failed to make a conquest of Hymenaeus (the letter-writer), who manages to escape its power by discovering that beauty burdened with bad character can be, and ought to be, resisted by someone searching for a suitable companion for life.

Eventually, however (as described in Rambler #167), Hymenaeus finds the right companion in Tranquilla. And even though the marriage is a happy one, it is not perfect: “As there are advantages to be enjoyed in marriage, there are inconveniences likewise to be endured.”

#10: Preserved So Long

Anatomists have often remarked, that though our diseases are sufficiently numerous and severe, yet when we inquire into the structure of the body, the tenderness of some parts, the minuteness of others, and the immense multiplicity of animal functions that must concur to the healthful and vigorous exercise of all our powers, there appears reason to wonder rather that we are preserved so long, than that we perish so soon, and that our frame subsists for a single day, or hour, without disorder, rather than that it should be broken or obstructed by violence of accidents, or length of time. (Rambler #45)

Blaise Pascal also lamented the frailty of the human body, but found an ennobling and redeeming quality in the human mind:

“Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature. The entire universe need not arm itself to crush him; a vapor, a drop of water suffice to kill him. But when the universe has crushed him man will still be nobler than that which kills him, because he knows that he is dying, and of its victory the universe knows nothing.”

But for a countervailing view of human strength:

Recently, rock guitarist Eric Clapton revealed that he is going deaf — an instance of a delicate part of the human frame “broken by violence” under extreme onslaughts of sound.

Eric Clapton

And yet:

Clapton was born in 1945. He has performed onstage, for over half a century, backed by towers of speakers thundering out sounds that could fill huge amphitheaters. Yet only now is his hearing beginning to deteriorate. A pity — but it was his choice to make, knowing that the continuous auditory blasting could eventually exact its toll from those delicate membranes that govern our hearing. He has achieved fame and his net worth today is around $250 million.

Were the rewards just compensation for the “violence” of the amplifiers?

Would you, fellow Johnsonian, be willing to trade your late-life hearing in exchange for professional success and $250 million?

As for Clapton himself, he has announced that he will continue to perform, though on a reduced schedule, clearly grateful that he has been “preserved so long.”

#11: Life Lessons

He that would pass the latter part of life with honour and decency, must, when he is young, consider that he shall one day be old; and remember, when he is old, that he has once been young. In youth, he must lay up knowledge for his support, when his powers of acting shall forsake him; and in age forbear to animadvert with rigour on faults which experience only can correct. (Rambler #50)

John Lavery, “Youth and Age”

My first introduction of Doctor Johnson’s writings came in a course on eighteenth-century literature taught at Harvard by Walter Jackson Bate. At the time, I was a young romantic who despised the rigorous forms of poetry and prose, and especially the didactic essays of Samuel Johnson. One of his essays, though, struck a strong responsive chord in me: Rambler #134, which explored the moral and intellectual dimensions of procrastination. Young as I was, Johnson’s essay struck me as a profoundly honest confession of a personal shortcoming, one that I shared.

Years later, when I was encountering difficulties attempting to finish my doctoral dissertation, I remembered Rambler #134 and reread what Johnson had to say. And for many years thereafter, when I was inclined to put off unavoidable necessities, Johnson’s words gave me encouragement:

When evils cannot be avoided, it is wise to contract the interval of expectation.

Thus, as I aged, I learned to accept without complaint those youthful errors in others which, I came to see, could not be cured with words alone. Only when those words are reread at a later time of life can their truths became confirmed by experience.

#12: Johnson Censured

There are few who do not learn by degrees to practice those crimes which they cease to censure. (Rambler #57)

When I first thought about commenting on this observation by Doctor Johnson, it seemed to me that, in the United States today, the clearest case of ceasing to censure a crime is the changing attitude toward marijuana. In spite of voters’ willingness to allow for the recreational use of marijuana in their states, federal law still criminalizes the sale, possession and use of the drug. The penalty for first-time offense for possession is “up to a year in prison and a $1,000 fine” for a third offense: “ mandatory minimum of 90 days (and up to three years) incarceration ands a $5,000 fine.” If one sells or grows more than 1,000 kilograms or plants, the penalty is “a felony involving between 10 years to life and a $1,000,000 fine.”

But how could I be sure that the people who use marijuana once censured its use?

I couldn’t.

I wasn’t satisfied with my thoughts on this subject, so I emailed three of my friends to get their reaction. Here is what they wrote:

1) “That is a bad statement. For starters it is convoluted and hard to parse. Seems like it has a double negative or two further obscuring the meaning. After some work I rewrote it in a simpler way:

Most gradually start committing those crimes they don't condemn.

“Written that way it does not seem like a great generalization. Sometimes true, sometimes not.”

2) “The statement strikes me as unjustified and cynical. Just because I have come to accept sex-change surgery doesn't mean I'm going to have it!”

3) “I’m not sure whether this quote qualifies as involuted or convoluted. I see your point about marijuana and another such example would be the amendment which once again legalized alcohol. But my immediate response was to think of Trump who has spent so much of his life cheating, lying, demeaning others, etc. that all these things now seem normal to him. But the quote is tricky, both grammatically and psychologically. It can be read either as human nature bending to habituation or as a moral choice, one of conscience or intellect. My view, though labored, is that the quote is too ambiguous to plant one’s feet or one’s argument on.”

If anyone else has contributions to make on this subject, I would be delighted to hear them.

#13: Firmness and Industry

“We are unreasonably desirous to separate the goods of life from those evils which Providence has connected with them, and to catch advantages without paying the price at which they are offered us. Every man wishes to be rich, but very few have the powers necessary to raise a sudden fortune, either by new discoveries, or by superiority of skill in any necessary employment; and among lower understandings, many want the firmness and industry requisite to regular gain and gradual acquisitions.” (Rambler #182)

Doctor Johnson goes on to describe how a fortune hunter attempts to snare a wealthy woman, but fails in every attempt. In the 21st century, the most obvious instance of people trying to acquire riches with little effort but a great deal of luck involves the purchase of a winning lottery ticket. Someone once called the lottery system “a tax on stupidity.” But aside from that quip, a state lottery constitutes an official encouragement by the government for its citizens to acquire riches unearned by “firmness and industry.”

The desire for easily obtained goods has long been part of human hopes, and is not always confined to wealth. In ancient Egypt, the ruler Ptolemy asked Euclid for an easier method of comprehending geometry than the laborious effort of reading through the mathematician’s demonstations. Euclid’s reply:

“There is no royal road to geometry.”

In other words, there are some accomplishments, like earned wealth and understanding of mathematics, that must be acquired though “firmness and industry.” Even so, technology has removed much of the drudgery of obtaining knowledge: calculating machines, computer language translation, google searches: all these aids do not remove the difficulty of conceptual thinking, but they do take away much of the drudgery of the task of learning.

In a wider context, the urge to take such shortcuts betrays a moral infirmity, an unwillingness to pay the price for what we desire. This urge bears a resemblance to cheating. After all, the road to hell, Virgil wrote, is all downhill and easy going:

Facilis decensus averno

He might have added, with Doctor Johnson’s approval, that:

Via est difficile ad caelum

“The road to heaven is difficult,” always requiring firmness of purpose and steady industry.

#14: Our Own Importance

"No cause more frequently produces bashfulness than too high an opinion of our own importance.” (Rambler #159)

A question related to Doctor Johnson's observation:

Is bashfulness related to stage fright? In the instance of a performance in front of an audience, however, the people who attend rightly expect the performer to please them and to execute his/her part with style and conviction. But the person who becomes tongue-tied when speaking to strangers, though, has no — or should have no — such expectations to fulfill. However, in both instances, it seems to be a case of lack of self-confidence, rather than “too high an opinion of our own importance.”

In an earlier Rambler (#159), Doctor Johnson observes that bashfulness is often only temporary, but may actual be a useful emotion: a proper restraint on our actions until we are accomplished enough to present our best efforts to the public:

"It generally happens that assurance keeps an even pace with ability, and the fear of miscarriage, which hinders our first attempts, is gradually dissipated as our skill advances towards certainty of success. That bashfulness, therefore, which prevents disgrace, that short and temporary shame which secures us from the danger of lasting reproach, cannot be properly counted among our misfortunes."

It is remarkable that Doctor Johnson should demonstrate an understanding of an emotion which, by all accounts, her never felt himself. The closest he ever came to doubting the power of his own character appears in this incident recorded by Boswell:

Once, when Johnson was ill, and unable to exert himself as much as usual without fatigue, Mr. Burke having been mentioned, he said, "That fellow calls forth all my powers. Were I to see Burke now it would kill me."

#15: Secretary of the London Garret

"So true it is that amusement and instruction are always at hand for those who have skill and willingness to find them; and so just is the observation of Juvenal that a single house will shew whatever is done or suffered in the world.” (Rambler #161)

This remark comes from an anonymous correspondent to the Rambler, a man who has made it his business to collect and study “the history and antiquities of the several garrets in which I have resided.” He discovers that his predecessor lodgers have been a dishonest tailor, a disreputable woman, a counterfeiter, a complaining promise-breaker, a vociferating arsonist, and a terminally ill old woman.

A distressed poet in a London Garret, by William Hogarth

The author of these observation draws no lessons from this cavalcade of human characters, but merely acts, as Balzac once said of himself, as a “secretary to society.” One can imagine what Charles Dickens might have made of the inhabitants of this garret. A more extensive Rambler-style essay might have yielded more considered applications to human life in general, perhaps along the lines of the Roman playwright Terrence’s confession:

"Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto”, (“I am human, and I think nothing of which is human is alien to me.”)

#16: Antiquarian Paradise

"To rouse the zeal of a true antiquary, little more is necessary than to mention a name which mankind have conspired to forget; he will make his way to remote scenes of action through obscurity and contradiction, as Tully sought amidst bushes and brambles the tomb of Archimedes.” (Rambler #161)

One of the greatest benefits of the Internet today is that it has provided new life for countless near-forgotten or neglected people and their works. As of 2016, the “indexed web” — that is, the internet accessible to search engines, a number much smaller than the total number of web pages that exist, since many cannot be fetched by google or any other popular search engine — is 4.62 billion. In one minute, seventy-two hours of new video are uploaded to YouTube, and 216,000 photos are added to Instagram.

And for the “true antiquary” of the internet: the Wayback Machine hold 240,000,000,000 URLs just waiting to be fetched.

By contrast, the Library of Congress holds a mere sixteen million books and approximately 120 million “other items and collections.”

The “true antiquary” now need not leave his/her computer terminal to find and revive the works — words, images, music, videos — of human beings, or indeed any creations of nature or fantasy, belief or speculation.

How long would it take for zeal to make use of all these riches?

I cannot imagine. But it is safe to assert that the human race should never be bored as long as these resources exist and grow.

However, all of our digital riches could prove as impermanent as the acquisitions of the Roman Empire:

#17: Wish Fulfillment

"Every man is rich or poor, according to the proportion between his desires and enjoyments; any enlargement of wishes is therefore equally destructive to happiness with the diminution of possession; and he that teaches another to long for what he never shall obtain, is no less an enemy to his quiet, than if he had robbed him of part of his patrimony.” (Rambler #163)

Johnson’s acute observations remind me of several subsequent maxims and aphorisms on the same subject:

Henry David Thoreau:

“That man is richest whose pleasures are the cheapest.”

Thoreau

This may be a consolation who those of us who are not gazillionaires. But most would confess that, regardless of the cost of their pleasures — philanthropy, space exploration, charitable endowments — that man is richest who has the most money.

Oscar Wilde:

“There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.”

Wilde

This notion is a hedonist’s idea of tragedy. We could all think of possessions we desired whose “not getting” was no tragedy. And the ennui which might follow getting what we want seems too pale an emotion to be called a tragedy. There are instances — marrying the wrong person, for example — which can be disheartening, and which can lead to tragedy. But such situations bring up the question of character flaws which led to the misfortune, and complicate the notion of “getting what one wants” as a source of tragedy.

Teresa of Àvila:

There are more tears shed over answered prayers than over unanswered ones.

Saint Teresa

This may or many not be true — who can compute all the instances of such prayers? — but it is profoundly cynical, and seems to urge us just to accept our fate without wishing for divine assistance.

Doctor Johnson’s words are far more sensible, in that they combine an assessment of human nature, based on proportion, and a caveat, not against hope and desire, but against those who raise hopes beyond the reach of fulfillment.

#18: Rashness and Cowardice

“It may, indeed, be no less dangerous to claim, on certain occasions, too little than too much. There is something captivating in spirit and intrepidity, to which we often yield, as to a resistless power; nor can he reasonably expect the confidence of others, who too apparently distrusts himself.” (Rambler #1)

“There are some vices and errors which, though often fatal to those in whom they are found, have yet, by the universal consent of mankind, been considered as entitled to some degree of respect … A constant and invariable example of this general partiality will be found in the different regard which has always been shewn to rashness and cowardice, two vices, of which, though they may be conceived equally distant from the middle point, where true fortitude is placed, and may equally injure any public or private interest, yet the one is never mentioned without some kind of veneration, and the other always considered as a topic of unlimited and licentious censure, on which all the virulence of reproach may be lawfully exerted.” (Rambler # 25)

Elsewhere, Doctor Johnson expands the principle of “correctable excess”:

It may be laid down as an axiom, that it is more easy to take away superfluities than to supply defects; and therefore he that is culpable, because he has passed the middle point of virtue, is always accounted a fairer object of hope, than he who fails by falling short. The one has all that perfection requires, and more, but the excess may be easily retrenched; the other wants the qualities requisite to excellence, and who can tell how we shall obtain them? We are certain that the horse may be taught to keep pace with his fellows, whose fault is that he leaves them behind. We know that a few strokes of the axe will lop a cedar; but what arts of cultivation can elevate a shrub? (Rambler # 25)

The central emotion supporting and sustaining rashness is courage, a universally admired character trait. Fear of harm or shame generates cowardice, and incurs the derision of those who are — or fancy they are — superior to those emotions. Johnson often comments on the human drive to establish superiority; and the detection, exposure, and contempt of cowardice allow all people, whose own courage is not known, to strut their sense of superiority at the expense of the coward.

In addition, rashness may lead to overwhelming tragedy, no matter how much it might be admired at the outset. Who admires Napoleon for his march on Moscow, or Hitler’s attempt at European domination? Our estimation of rashness must be tempered by the nature of the goal rashly pursued.

But perhaps Doctor Johnson attributes too much inalterability to cowardice. A shrub’s biological structure prevents it from reaching great height. But timidity may be brought under control, and modified by some measure of courage. Neither courage nor cowardice is unalterable in the human heart.

Finally, here is Miguel de Cevantes view of these two extremes:

“Valor lies just halfway between rashness and cowardice.”

#19: Lessons from the Library

In the past, many such books crowded the shelves of public and university libraries. The volumes appeared headed for slow, sure extinction, since they had not been checked out for decades, nor were they ever likely to be read in the future. But the current digitization of books, begun by the Gutenberg Project and carried forward by the likes of google and amazon, give these neglected books new life. A neglected volume on a library shelf has little chance of discovery; but a digitzed book or magazine, available to anyone with a computer connected to the internet, may be discovered by a search engine and brought back to life.

#20: Reason

“Reason is the great distinction of human nature, the faculty by which we approach to some degree of association with celestial intelligences” (Rambler # 162)

Acccording to Wikipedia, “Reason is the capacity for consciously making sense of things, establishing and verifying facts, applying logic, and changing or justifying practices, institutions, and beliefs based on new or existing information.” Or, as Immanuel Kant put it: “All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.”

Nothing higher — not faith, authority, intuition, or any other human approach to reality which cannot, by the nature of its structure, be proved true or false. Doctor Johnson, though himself a man of faith and believer in the objective existence of virtue and vice, clearly recognizes that there is something about reason that partakes of the divine: a point of view that understands the world as a whole, made of by parts whose existence and function can be grasped by the process of reason.

#21: Ruined Reputation

"Miscarriages by any subsequent achievement, however illustrious, yet the reputation raised by a long train of success may be finally ruined by a single failure; for weakness or error will be always remembered by that malice and envy which it gratifies.” (Rambler #207)

And as Napoleon said: “It is but a step from the sublime to the ridiculous.”

Anyone watching the debacles of sexual abuses in the United States can bear witness to the number of people — mostly men — who have risen to the heights of their professions, only to be brought to earth (or lower) by allegations and proofs of sexual wrongdoing: Joe Paterno, Bill Cosby, Peter Martins, James Levine — these are only the front-page names whose reputations have been ruined by sex scandals.

[This just in:

“More than 20 Red Cross employees were fired or quit over alleged sex misconduct since 2015”]

But for the news media, these crimes and humiliations are wonderful for business. Many of the stories themselves, and their editorial thunderings, would surely be classified by Dr. Johnson as motivated by “malice and envy.”

A further thought: if the secrets of the newspeople’s own lives were subjected to open scrutinty, “who should ‘scape whipping?”

None of the above should be taken as an excuse for the sufferings caused by sexual predators or their enablers. But which of their accusers should be rightfully empowered to cast the first stone?

#22: Rewards

“While a rightful claim to pleasure or to affluence must be procured either by slow industry or uncertain hazard, there will always be multitudes whom cowardice or impatience incite to more safe and more speedy methods, who strive to pluck the fruit without cultivating the tree, and to share the advantages of victory without partaking the danger of the battle.” (Rambler #131)

And again:

"He that embarks in the voyage of life, will always wish to advance rather by the impulse of the wind, than the strokes of the oar; and many founder in the passage, while they lie waiting for the gale that is to waft them to their wish.” (Idler #2)

Most of us wish for the aquistition of a skill or fortune that will bring us riches, honor, or contentment. But there will always be those who act on the urge to “share the advantages of victory” without the necessary labor of thought and action to acquire those advantages.

Thus the common ground of the thief and the purchaser of lottery tickets.

****

I once asked a juggler, who was working very hard at mastering a seven-ball cascade, if he would take a pill that would instantly grant him the ability to be proficient in the skill he was working on.

“No,” he replied.

“Why not?” I asked him.

“Because then the skill wouldn’t mean anything,”

#23: Social Virtue

Society is the true sphere of human virtue. In social, active life, difficulties will perpetually be met with; restraints of many kinds will be necessary; and studying to behave right in respect of these is a discipline of the human heart, useful to others, and improving to itself. Suffering is no duty, but where it is necessary to avoid guilt, or to do good; nor pleasure a crime, but where it strengthens the influence of bad inclinations, or lessens the generous activity of virtue. (Rambler #44)

Suffering:

Martin Luther King, Junior, observed that “unearned suffering is redemptive.” And, since courage is a prerequisite for redemption, William Tecomsah Sherman’s definition of that quality comes to mind: “I would define true courage to be a perfect sensibility of the measure of danger, and a mental willingness to incur it.” So there are circumstances — fighting for freedom, fighting a war for the sake of freedom — in which suffering exists as a concomitant risk of duty.

Pleasure:

As for pleasure, Doctor Johnson stresses the inner costs of criminal pleasure. Tainted pleasurable emotions always and inevitably degrade the person who indulges them: their indulgence either weakens our own resolve not to give into damaging impulses, or disinclines us to be generous toward other people.

#24: “Resentment is a union of sorrow with malignity.” (Rambler #185)

Here are three quotations on the subject of resentment written by a saint, a basketball coach, and a medical doctor, all of whom had a chance (or mischance) to deal with the emotion in context:

“Resentment is like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die.” — Saint Augustine

“A coach is someone who can give correction without causing resentment.” — John Wooden

“Parents are perhaps the most common object of resentment, the people who are most frequently blamed for all our failings and failures alike.” —Theodore Dalrymple

I’ll only add that, if you look at the google entries under resentment, you’ll find political pundits ascribing Donald Trump’s appeal to “white resentment.” However, there are also entries for “black resentment.” So perhaps Doctor Dalrymple’s categorization needs expansion. The imputation of guilt, central to all feelings of resentment, can spread to any human endeavor where blame can be assigned.

And finally, here is a splendid speech from Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, in which Father Zosima speaks to the buffoon Fyodor Karamazov:

"You know it is sometimes very pleasant to take offense, isn’t it? A man may know that nobody has insulted him, but that he has invented the insult for himself, has lied and exaggerated to make it picturesque, has caught at a word and made a mountain out of a molehill—he knows that himself, yet he will be the first to take offence, and will revel in his resentment till he feels great pleasure in it, and so pass to genuine vindictiveness."

#25: Virtue and Courage

"The utmost excellence at which humanity can arrive is a constant and determinate pursuit of virtue without regard to present dangers or advantage” (Rambler #185)

It is, of course, possible to be courageous in pursuit of an evil goal. The laws of the land have enforcement agencies (laws, police, prisons) to oppose such pursuits. But why would it take courage to pursue a virtuous one? Because there are those who would oppose you, either because they believed your goal to be evil (or at least self-serving), or because they wanted possession of the goall all for themselves alone?

General Tecumseh Sherman remarked: “I would define true courage to be a perfect sensibility of the measure of danger, and a mental willingness to incur it.” For a military man, courage would be defined in terms of a willingness to risk life in in pursuit of a cause worth fighting for. In that sense, according to Dr. Johnson, the “utmost excellence” derives its worth from that willingness.

#26: Money and Happiness

“How man things are necessary to happiness which money cannot obtain!” — (Rambler # 189)

Another perspective:

“Whoever said money can’t buy happiness isn’t spending it right.” from a Lexus automobile ad

So, in accordance with the Lexus proposition, one Harvard researcher (Dan Gilbert) finds that we are much more likely (57%) to be happy spending money on experiences than on material purchases (34%). However, these expenditures are evidently for enjoyment, not for the preservation of life or the amelioration of suffering. A trip to Paris may well bring more long-term satisfaction than the purchase of an expensive wristwatch. But it seems to me that the purchase of medicine to reduce the pain and discomfort of asthma attacks would be “worth” more than the trip to Paris.

The list of “free” requirements for happiness is not hard to summon up: love, satisfaction in career pursuits, health, and much more. Yet, though money cannot purchase these necessities directly, it is difficult to enjoy them in a state of poverty and want. Expensive drugs may not bring health; but they might, and also bring relief from pain. In a situation of extreme poverty, love can still exist, though the pressures of want can end love through constant argument and suffering. A well-funded group of competent asssistants can mean the difference between success and failure — a success perhaps unliklely or impossible without that financial support.

#27: Mistrust

“But as it is necessary not to invite robbery by supineness, so it is our duty not to suppress tenderness by suspicion; it is better to suffer wrong than to do it, and happier to be sometimes cheated than not to trust.” (Rambler #79)

A century before Johnson wrote this passage, the Duc de La Rochefoucauld expressed a similar distrust of suspicion:

Distrust on our part justifies deceit in others. (Notre défiance justifie la tromperie d’autrui.)

It is possible that suspicion and resentment (discussed in an earlier Ramblings post) stem from the same inner urge: the desire not to be cheated. In the cases of suspicion, Johnson and La Rochefoucauld indicate that there is a kind of inner corruption of the human spirit that emerges when we place ourselves in antagonism to the imputed motive behind the acts of other people. The key word, of course, is imputed.

Two more brief and thoughtful perspectives on the corrosive nature of suspicion:

Suspicion is a heavy armor and with its weight it impedes more than it protects. — Robert Burns

Suspicion is the cancer of friendship. — Petrarch

#28: Security and Despair

“Such, indeed, is the uncertainty of all human affairs, that security and despair are equal follies; and as it is presumption and arrogance to anticipate triumphs, it is weakness and cowardice to prognosticate miscarriages.” (Rambler # 43)

Doctor Johnson often speaks about the twin excesses of arrogance and cowardice, and here he undertakes to correct both shortcoming in the conduct of our affairs in business and personal life. As with rashness and cowardice, there is a just balance between the two; but in that pair, he notes that rashness always carries with it a certain bravado that wins applause, and that its overabundance can more easily be brought under control than the retreat of cowardice before opposition.

However, in the case pf anticipating triumphs and prognosticating miscarriages, there is surely some use in carrying forward with confidence on the one hand, and devising a “Plan B” on the other. Hope and fear — the ever-present motivators of human action that underlie anticipation and pessimism — should each contain some admixture of the other.

#29: Sorrow and Employment

“The safe and general antidote against sorrow is employment.” (Rambler # 47)

In a letter to Boswell, Doctor Johnson cited his source for the amelioration of sorrow Ricard Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy:

“The great direction which Burton has left to men disordered like you, is this, Be not solitary; be not idle: which I would thus modify;—If you are idle, be not solitary; if you are solitary, be not idle.”

As Johnson notes, the common element in both “antidotes” is engagement: interacting with other people and using the mind to focus on something outside one’s own private griefs.

Even with these admonitions, though, there must be some qualifications. If we weary our listeners’ attention with a stream of complaints, we do little to relieve our own miseries, but add to the discomfort of our company:

“Complaint quickly tires, however elegant, or however just.” (Rambler #73)

Even solitary employment can fail to provide relief if we turn to tasks that we can perform automatically, leaving our minds to brood. So the anti-sorrow antidote task must have just right mixture of difficulty and ease of accomplishment to work its cure.

#30: Desisting

"I have now determined to desist.” (Rambler #208)

On March 14, 1752, Samuel Johnson published the final number of his Rambler. After writing almost all of the 208 issues, he decided to devote his energies to other projects. But ever afterward, he spoke very fondly of his achievements in the pages of the Rambler:

"My other works are wine and water; but my Rambler is pure wine."

Likewise, after scarcely more than three months, I have decided to cease sending my Ramblings to the Johnsonian list. Whether many people read my responses to Johnson’s ideas, or whether subscribers merely hit the delete key when my post came into their email inbox, I have no idea. But for myself, the exercise has been an enjoyable venture; and, for those who took the trouble to read and think over some of my ramblings, I thank you for your attention.

-- Arthur Chandler, April 3, 2018

#31: Health

“It may be said that disease generally begins that equality which death completes; the distinctions which set one man so much above another are very little perceived in the gloom of a sick chamber.” — Rambler #48

“From having wishes only in consequence of our wants, we begin to feel wants in consequence of our wishes.” — Rambler #49

“Consolation, or comfort, are words which, in their proper acceptation, signify some alleviation of that pain to which it is not in our power to afford the proper and adequate remedy; they imply rather an augmentation of the power of bearing, than a diminution of the burden.” — Rambler # 52

The great end of society is mutual beneficence.” — Rambler #56

Johnson on his own achievements with the Rambler

“Something, perhaps, I have added to the elegance of its construction, and something to the harmony of its cadence.” — Ramber #208

Dreams and Schemes

Few moments are more pleasing than those in which the mind is concerting measures for a new undertaking….

The heart dances to the song of hope…

We proceed because we have begun; we complete our design, that the labour already spent may not be vain; but as expectation gradually dies away, the gay smile of alacrity disappears, we are compelled to implore severer powers, and trust the event to patience and constancy…

If the design comprises many parts, equally essential, and therefore not to be separated, the only time for caution is before we engage; the powers of the mind must be then impartially estimated, and it must be remembered that not to complete the plan is not to have begun. — Rambler #207

“In the esteem of uncorrupted reason, what is of most use is of most value.” — Rambler # 60