by

Arthur Chandler

Reprinted from The New Mexico Humanities Review, fall, 1985

Centuries before the invention of photography, European artists established rules to attain the highest goal of painting: to capture the Significant Instant -- the moment when the face or the act reveals the essence of the personality or the event -- and to embed that picture in the inviolable spatial order of perspective.

This is the world of visual expectations inherited by photographers in the last century. And so, from the earliest years in the history of photography, lenses that would produce pictures in normal perspective were adapted to cameras. Shutter and film speeds were made faster and faster, in pursuit of the instantaneous image. By the 1850s, photographers could render scenes frozen at 1/50 of a second, in "true" perspective. Only color was lacking, it seemed, to make the photograph in every way the equal of painting -- and perhaps its superior in fidelity of detail.

Consider the two pictures of John Brown the Abolitionist.

Note: an M.D. friend believes that Brown's face shows classic symptoms of "Bell's Palsy."

Here, the question of the nature of the photograph emerges in full force: just what are we seeing in the image -- a quintessence of character, or the accidental play of features at the moment? Judged by the canons of interpretation drawn from art, the daguerreotype shows us a bleary-eyed fanatic. The engraving -- taken, as it happens, not from life but from this very photograph -- transforms him into a Noble Reformer. The watery eyes now glow with benevolent intelligence, and the stubborn set of the lips becomes Firmness of Purpose. There is little doubt about what the engraving is trying to tell us. But what do we learn from the photograph? Nothing? -- except that on a certain day, in a certain light (translated into shades of black and white), seen from a certain angle, John Brown looked like this? Or something crucial? -- that the man whom the engraver presented as a noble reformer, was in fact a bleary-eyed fanatic?

Without knowing anything about the events leading up to and surrounding the taking of this picture, we can tell nothing about John Brown's character. Perhaps the camera caught his face at a moment of fatigue. His features might have been temporarily disarranged after a yawn, a cough, or an unpleasant memory. Without some other source to explain the context of this photograph -- or any other picture of the man, flattering or not -- we will never know what Brown's expression means.

* * * * *

Even in the early years of photography, few observers were deceived by the superficial similarity between the old art and the new invention. There was already an intuition that the two forms were worlds apart. But painting was the older, more venerable enterprise. It was photographers who felt that they, too, could and should capture the Essence of Things with their sunpens. And so began the quest for the Art of Photography.

From the outset, it was recognized that the painter is in some sense freer than the photographer. The painter can conjure up souls long since vanished from the face of the earth, or place all people -- real or imagined -- on his canvas stage in preplanned attitudes of hope or despair, rage or indifference. The world behind the picture plane is the artist's own. Ultimately, of course, this world derives from the painter's observations of life, from reading, from other paintings, or from any source that can be transmuted into art. But the final product is recast in forms and colors with a unique rhythm of visual imagining. The painter's works are ideas made manifest.

The options of photographers are far more restricted. They cannot, without resorting to patent trickery, create new landscapes or alter the contours of existing ones. They cannot photograph Caesar or Christ. They cannot go out into the streets and make every man and woman assume picturesque bearings and expressions. To a degree impossible for painters, photographers must take the world as they find it, even though they select what they choose to record.

Painting, in its major phases in the West, implies the existence of other worlds more perfect than our own. It shows us a reality that we know, but do not or cannot see in the world around us. Even the most naturalistic styles of landscape and portrait painting yearn to reach beyond the surface of appearances and capture the essence of the scene or the face -- an essence which may not be visibly present, but which permeates it as its most significant form. Painters are, by the nature of their calling, Platonists: they want to show the truth of the reality behind the surface, the Truth inherent in the facts. For the viewers as for themselves, artists attempt to transform natural vision.

Photography is the realm of reflected light -- not the light shining in Plato's cave, but the beams of the passing sun. Unlike painting, in which the surface is built up stroke by stroke, the photograph is made all at once (subsequent darkroom work only refines what is already there). Because of this intimate and immediate relationship to the present, photography is a kind of chronicle. It is ill-adapted to show "other worlds," such as those that religious or historical painting can create -- witness the ludicrous attempts of Victorian photographers straining after the Grail of Art, to pose a Mrs. Hillier as the Virgin Mary, or three stout Liverpool ironworkers as the ancient Horatii warriors swearing their oath of allegiance.

Julia Margaret Cameron, "Madonna and Child" (Mary Hillier and Percy Keown), 1856

Portraiture would seem a far more congenial mode for photography. Here, if anywhere, would be the opportunity to find and capture the essence of character in a physical presence. But when we attempt such a character interpretation from a photographic portrait, we find ourselves at once forced to believe in a kind of incarnation: if the photograph says anything at all about the essence of a character, the spirit must be made flesh. To believe that a photograph can capture such a spirit, we must have full faith that the moment's configuration of gesture, bearing, set of the lips and focus of the eyes will add up to a totality that expresses something essential about the person being photographed.

Honoré Daumier, a declared enemy of the artistic pretensions of photography, believed otherwise. "Photography," he asserted, "describes everything and explains nothing." His implication is clear: only an art, in which the imagination exercises full freedom, can interpret reality. Photography, bound as it is to one actual moment in one segment of real space, can never be more than the record of an act.

Daumier's satire on "Photography: the new procedure for capturing graceful poses"

In one sense, the argument against Daumier was stronger in the early years of photography than it is now. Before 1860, almost all pictures of people were posed and paid for by the sitter. Subjects would dress up in their best clothes, sit before the photographer's camera, then draw themselves up into attitudes they believed should be read as the important side of their personalities -- hence the seriousness of most nineteenth-century portraits. Therefore, in the photography of that era, there is a potentially decipherable correspondence between the self-image of the sitter and the image produced by the photographer.

But even in the heyday of posed pictures, there was the very real possibility that the split-second exposure might capture an expression not agreeable to anyone but the sitter's enemies. And with the development of ever-faster film and more portable (and less noticeable) cameras, candid photographs upset the balance of agreement between photographer and subject.

The best we can hope for is to believe that such images give us insights into the mood and tenor of passing moments. A face contorted in fear, hands folded in resignation, a body caught in the sway of dance -- these surfaces might express fleeting passions. A photographer possessed of a precise sense of timing -- the "decisive moment," Henri Cartier-Bresson names it -- might capture such instants on film. But to assume that Cowardice, Resignation, or Abandon is the predominant essence of the person or the act being photographed is to leap from the particular to the general. Painting, in its inspired moments, strives to make just such a leap. But photography, the chronicle of the transient and specific, remains faithful to the moment.

In this very fidelity to the moment, we can find one domain where photography establishes its primacy over traditional art. A painting is most valuable, best fulfills the potential of its nature, when it shows us the universal behind the particular; photography, when it preserves for us something that time must destroy. So a scenic shot of Yosemite taken in 1851 fails to move us today, except in such matters as the qualities of the print made by a process long since abandoned. But a photograph of San Francisco taken at the same time -- an image which shows us men in beaver hats and women in wide bonnets walking the planked streets, store signs advertising whale oil and hot baths, buggies and wagons strapped to the iron rings of hitching posts -- this fading memento of a time gone by in a place we know can move us with a sense of history that no painting, no novel or drama, can ever emulate. Capturing the transient surface of things -- no art has ever exercised such power to rescue the visible world from decay.

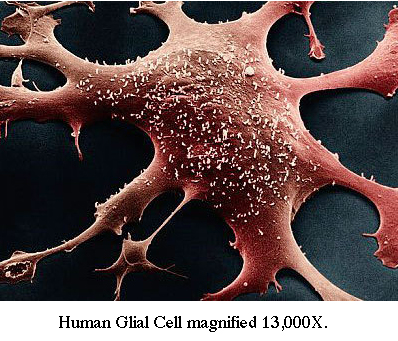

A second major strength of photography is its ability to extend our vision into alien spaces. Special lenses and films give us access to worlds illuminated by invisible light, microcosms beneath the threshold of sight, and macrocosms beyond the range of the unaided eye. X-rays, infrared pictures, Kirillian aura-images, cellular groups magnified 10,000 times, observatory photographs of other galaxies, and especially the Apollo pictures of earth seen from outer space -- these images have qualitatively changed our ideas about the range and structure of the physical world.

The camera can reach deeper into the world than our eyes; and with every new exploration of lighted space, photography adds to the content of our collective imagination. Such pictures may have no power to show us the Truth behind the shadows of Plato's cave. But at its best, photography opens out our power of sight in a way that shows us how vast and intricate those shadows really are, and fixes their fleeting surfaces on film before the restless sunlight passes into other moments.

Bibliography of Ideas

You see someone on the street, and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw.

— Dianne Arbus

To us these pictures seem a mistake. At best, we can only hope to get a naturalistic rendering. Ideality is unattainable — and imagination is supplanted by the presence of fact.

— article in The Athenaeum, 1845, criticizing an exhibition of photographs depicting posed dramatic scenes

The photograph as such and the object itself share a common being, after the fashion of a fingerprint.

— André Bazin

An instantaneous photograph could not distinguish a living animal from a dead.

— R.G. Collingwood

Photography describes everything and explains nothing.

— Honoré Daumier

The two images, that of the sitter and that of the photo portraitist, are locked in a silent wrestle of imaginations until they are thrust apart by the click of the shutter. At that moment the issue is resolved, but not necessarily in favor of either of the contestants.

— Harold Rosenberg

The ultimate wisdom of the photographed image is to say: "There is the surface. Now think — or, rather, feel, intuit — what is beyond it." Strictly speaking, there is never any understanding in a photograph, but only an invitation to fantasy and speculation.

— Susan Sontag

It is doubtful that a photograph can help us understand anything. A photograph of the Krupp [munitions] factory, as Brecht points out, tells us little about this institution. The "reality" of the world is not in its images, but in its functions. Functioning takes place in time, and must be explained in time. Only that which narrates can make us understand.

— Susan Sontag

I am no longer trying to "express myself," to impose my own personality on nature, but without prejudice, without falsification, to become identified with nature, sublimating things seen into things known — their very essence — so that what I record is not an interpretation, my idea of what nature should be, but a revelation — an absolute, impersonal recognition of the significance of facts.

— Edward Weston

Whatever may have been the case in years gone by, the true use for the imaginative faculty of modern times is to give ultimate vivification to facts, to science, and to common lives, endowing them with the glows and glories and final illustriousness which belong to every real thing and to real things only.

— Walt Whitman

Reprinted from The New Mexico Humanities Review, fall, 1985