Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

Click the image for a lightbox view

"Although Americans are generally awkward and unbending, they enjoy dancing, and above all they love to watch other people dance. At the public dances in San Francisco all the women in town appear, French, American, and Mexican; the men gather in crowds; and one often sees beautiful costumes richly adorned with lace, which the women make themselves or order from dressmakers for each occasion. A masked ball naturally permits a certain freedom; but here the feverish atmosphere of the city produces an abandon I have never seen elsewhere...

"Three distinct quadrilles are always in progress simultaneously, French, American, and Mexican, and the races [sic] mix only in waltzes, polkas and gallops. The American quadrille is danced with Anglo-Saxon stiffness and passivity; the Mexican with a southern languor and indolent grace; but the French quadrille is the center of genuine gait and animation. I often notice how American men steal away from their own group and enviously watch the vivacious French women, who do not hesitate to let themselves go when they see they are being admired.

"I am occasionally reminded of our balls at the Salle Valentine on the Rue St. Honoré. There is one important difference: Parisian rowdies often come to blows; but in San Francisco hardly an evening passes without drunken brawls during which sorts are fired."

-- Albert Benard de Russailh, Last Adventure (1851)

Fight at the Rouge Gorge Dance Hall, Paris, 1840s

From the Marcel Carné film, Children of Paradise

Here is the equivalent episode in San Francisco:

"Last April, the actors in the French Theater got up a ball, and Charles Duanc, who is presentable and well-mannered, attended the party. Halfway through the evening, in the midst of the laughing and stamping of the dance, a quarrel broke out between Duane and an actor named Fayolle, who had accidentally stepped on Duane's foot. In fear, everyone stopped dancing.

"Fayolle was very apologetic, but Duane's rage flared up when he saw that the Frenchman wanted to avoid a fight. Some men intervened, separated the two, and pacified Duane. who seemed ready to leap at Fayolle. At last everyone thought that the quarrel was settled; but they had not reckoned onDuane's thirst for blood.

"A quadrille began, and Duane moved up behind Fayolle, who was dancing. When the dance was over, Duane coolly drew his revolver and shot Fayolle in the back.

"The actor fell severely wounded, and lay in a pool of his own blood. At the sound of the shot all the women either fainted or ran away. As for Duane, he stood calm and impassive over his victim, apparently contemplating his handiwork with satisfaction, and calmly took out a cigar from his pocket. "

In spite of the violence, the spirit of democracy prevailed on the dance floor in Gold Rush San Francisco:

The artist who gave us the above image of a Gold Rush dance hall was Charles Christian Nahl, who came to the western shores to seek his fortune in the gold fields, but remained to become the foremost chronicler of life in California in the nineteenth century. Here is a link to his major works:

Click the image for a lightbox view

Commentary

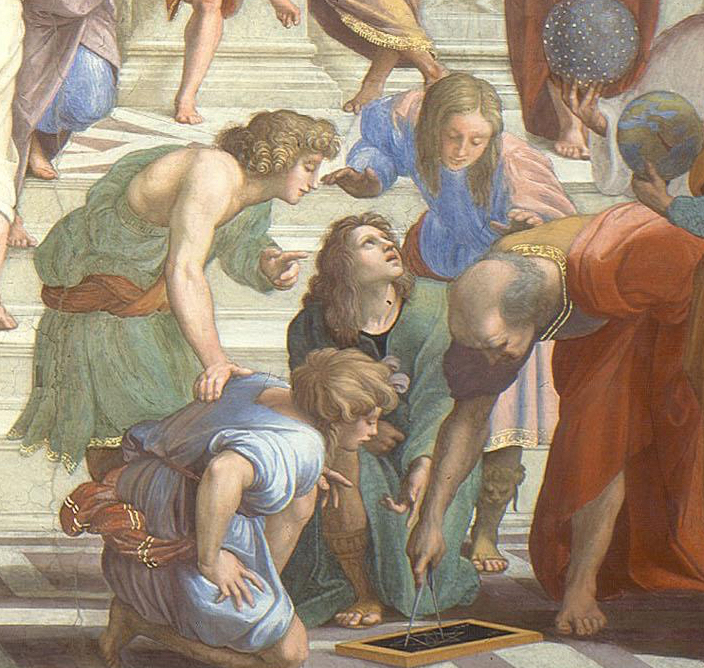

The masked balls in Europe probably began in France during the fourteenth century, as seen in this illustration of the Bal des Ardents in 1393, with King Charles VI and the Duchess of Berry in costume:

As it developed through the years, such events became a kind of adult version of Halloween: a time and place where mild wickedness was allowed to flourish, a temporary relaxation of the rules of ordinary decorum. During the nineteenth century in Paris and Brussels, the masked ball was an upper class affair, set in the dazzling splendor of ballrooms and opera houses: a stage set where high society men and women could carouse and flirt — sometimes with serious amorous intent.

The world of Gold Rush San Francisco was a far, far cry from such a society. As Bayard Taylor remarked: “Dress was no gauge of respectability, and no honest occupation, however menial in its character, affected a man’s standing,” and that “a man who would consider his fellow beneath him, on account of his appearance or occupation, would have had some difficulty in living peaceably in California.”

But the men who returned from months of hard mining labor in the mountains wanted as much entertainment as they could get to make up for the privations they had been through. They wanted to eat, drink and dance at as high a level as their new-won gold could purchase. The standards of the old world prevailed — champagne to drink, masked balls for dancing — but the free-for-all society of San Francisco meant that they had to make do with whatever, and whoever, was available. Here is a summary of the atmosphere of such dances, as reported in The Annals of San Francisco (1855):

Occasionally a fancy-dress ball or masquerade would be announced at high prices. There the most extraordinary scenes were exhibited, as might have been expected where the actors and dancers were chiefly hot-headed young men, flush with money and half frantic with excitement, and lewd girls freed from the necessity of all oral restraint.

In spite of their obvious differences, all dance venues demonstrate the truth of Paul Valéry’s insight that dance is the pure act of metamorphosis. For an evening, men and women, separately and together, enter into the world of moving music and rhythmic motion. Manet, Hermans and Nahl give us glimpses into those evenings, long since vanished, but still with us in their renderings.