THE PARIS EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE, 1889

by

Arthur Chandler

Revised and expanded from World's Fair magazine, Volume VII, Number 1, 1986

In the year 1889 there was revolution in Paris. No shots were fired, no buildings torched, no palaces looted. But on the Champ de Mars and the Esplanades des Invalides, the past and the future fought a world war of ideas. Iron battled stone, Javanese ritual music defied the siege of German orchestration, electricity triumphed over gas. It was a year to celebrate a revolution's centennial, a time to consolidate one hundred years of industry, art and social ideals that flowed from the great events of 1789.

COSTS AND CONSEQUENCES

In the early 1880s, it appeared that Paris might not again host an international exposition. The previous one had lost money. In spite of the constant stream of boasting in the French journals reporting on the 1878 fair, there was no getting around the stark fact that the 1867 exposition universelle – the culminating festival of the now-despised Second Empire – had produced a profit of almost three million francs, while eleven years later the Republic's world's fair lost more than thirty million francs.

There was a bright side to these comparisons, however. Less than seven million people had attended the 1867 fair. Over sixteen million had come to the 1878 exposition. Clearly, here was statistical proof that The People had responded more warmly to the Republic. So, despite the pundits' predictions of financial catastrophe, the leaders of the government of France decided that the birth of the Republic should be celebrated and vindicated in 1889, the centennial year of the French Revolution. Therefore, intoned Monsieur le President Jules Grévy, be it decreed on this eighth day of November, 1884, that there shall be held, from May sixth until November sixth, 1889, the fourth exposition universelle. Antonin Proust, Minister of Instruction and Fine Arts, was appointed President of the Exposition. A distinguished group of experienced men were placed in charge of the financing, building, and arranging of the Exposition Tricolorée – so-named for the colors of the French flag adopted during the Revolution – Paris would once again play host to the world.

Antonin Proust, Exposition President, in 1889 -- etching by Anders Zorn

The whole financial basis of the exposition was devised so that the affair would show a profit. The government, which had borne the entire cost of the three previous Paris expositions, paid for less than a third of the costs of mounting this fair. The city of Paris defrayed some of the expenses; but more than half the money was raised by an investors' guaranty association. This parsimonious approach to expenditures did help the exposition to realize a profit of eight million francs. But, as we shall see, the government would have done even better if the exposition committee had struck a shrewder bargain with Monsieur Eiffel.

Even with the experienced Antonin Proust at the helm, the project had to withstand several assaults from the forces opposed to the government's plans. To begin with, there were those who saw no good at all in hosting such a show. These critics remembered not only the financial loss of 1878, but the shortage of hotel space, the high cost of food, the traffic jams, and other inconveniences caused by the huge crowds of fairgoers. Paris was discovering by experience that hosting an international exposition entailed a number of costs, risks, and inconveniences for the permanent residents.

Moreover, even among supporters of the exposition, there was fear that the plethora of major shows in 1888 – the Exposicion Universal de Barcelona; the Grand Concours Internationale des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Brussels; the International Exhibition in Glasgow, Scotland; the Centennial International Exposition held in Melbourne, Australia; and the Centennial Exposition of Cincinnati, Ohio – would diminish participation at the Parisian fair the following year. The late nineteenth century was witnessing an explosion of such expositions: full-blown international fairs, as well as lesser events devoted to patriotic celebrations, and gatherings designed to bring together the latest inventions or improvements under the rubric of a theme such as electricity, cotton, etc. Such events, though laudable in themselves, could diminish the attendance at the Parisian exposition.

Some influential leaders thought that France should not risk another international exposition under any circumstances. Frédéric Le Play, chief commissioner of the 1867 exposition, relentlessly predicted that the 1889 exposition was doomed. In his own report to the Emperor Napoleon after the 1867 exposition, Le Play warned against trying to host a series of such events in which each one would be attempt to outdo its predecessor in size and splendor. Le Play argued, to Napoleon III in 1867 and to Jules Grévy in 1884, that the country would be better advised to invest in a permanent exposition site where there would be permanent facilities for changing exhibitions, provisions for restaurants and a greensward. Furthermore, he argued, such expositions should be specialized so as to draw only those visitors who were professionally interested in the theme of the exposition.

Proust and his fellow commissioners listened politely, but ultimately dismissed Le Play's novel idea as impractical and too limited in its ambitions. The 1889 commission was committed precisely to what Le Play was warning against: a colossal affair that would draw huge crowds from all walks of life, and from all over the world. In the long run, the old monarchist's vision was more revolutionary than that of the Republicans. Not for many decades would government officials think about designing permanent exposition spaces along the lines that Le Play first suggested in the 1880s.

A more compelling challenge came from those old rivals of Paris: the other cities of France. Nice had successfully mounted a modest world's fair in 1883. International expositions had even been held in foreign colonies from Cape Town to Calcutta. Why, then, should Paris always be the focus of French international expositions? A battle of wills ensued in the French legislature. But Paris, as always, had her way. The small cities argued, lost, and were humiliated in their defeat as the exposition authorities commandeered the choicest paintings and sculptures from municipal collections, and transferred them to the retrospective gallery at the Fine Arts Pavilion in Paris.

In an attempt to mollify the provincial authorities, the central committee of the exposition decided to hold a grand Mayors' Banquet in the old Palace of Industry. All the mayors from each of the 86 departments of France were invited, and most of them showed up. It is difficult to assess just how effective this gigantic feast was in assuaging the egos of provincial administrators. But the Parisian newspapers gave the event mixed reviews. For some, such as La Bataille, the event represented "the triumph of democracy," and, into the bargain, symbolized the government's victory over "the Boulangist reptiles."[1] Le Pilori, true to its name, presented the whole event as a cartoon strip, with words to be sung to the tune of "Auprès de ma blonde": officials arrive from the countryside, make pigs and fools of themselves (even vomiting out the contents of their overstuffed stomachs), and finally stagger home – after having mulcted the public of 800,000 francs to pay for the affair.[2]

Banquet of Mayors, 1889

The decision to celebrate the centennial of the Republic at the exposition brought other difficulties to the exposition authorities. A number of foreign monarchs voiced their reluctance to participate in a festival that celebrated revolution. As a result, sixteen of the forty-three nations represented were there unofficially – that is, without the official sanction of the home governments. Great Britain, Italy, Russia – some of the most important powers in Europe officially ignored the exposition universelle of 1889. It was a test for the Republic: were the attractions of Paris, and the opportunities afforded by any exposition held there, strong enough to attract exhibitors and visitors from these nations?

They were; and the result was that the attendance at the 1889 exposition was three times that of the combined attendance figures for the 1855 and 1867 expositions. World's fairs, and especially those staged in Paris, had become so important that no nation of any standing or pretensions could afford to be absent. The opportunities for industrialists, artists, and national governments to speak to an audience of tens of millions all at once were too rich to be ignored.

There was still the question of expense, however. The 1867 exposition universelle, the only profitable Parisian exposition to date, came out 2,880,000 francs in the black. The 1855 and 1878 ventures had not fared so well. But the commissioners of the fourth exposition were convinced that, with shrewd financial management, the government of France and the city of Paris would at least suffer no great loss. And in the end, their optimism was justified. After the gates finally closed, the Exposition Tricolorée commissioners reckoned their fair's profit at 8,000,000 francs.

Finally, there was the heritage: the 1867 exposition left only legacy an ornate reduced replica of a Tunisian Palace, transformed into an observatory and moved to Montsouris Park. The legacy of 1889: the Eiffel Tower.[3]

300 METERS TALL

When the exposition president, the three directors general and the numerous commissioners met, they agreed that the 1889 exposition should feature something special: a clou -- the "spike" that would give the entire fair a single signature structure, a striking symbol of French culture. The Committee decided that this spike should be a 300 meter tower – a structure far surpassing in height any edifice ever built.

Was it Gustave Eiffel himself who first suggested the idea to the committee? Alfred Picard, author of the final report of the exposition commission, traced the idea back through several predecessors. In 1833, a British engineer named Trevithick proposed a 1,000-foot (305 meters) cast iron column to commemorate the Parliamentary Reform Bill in England. A similar idea, drawn up by the American engineers Clark and Reeves for the centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, likewise never went beyond the planning stages. But these were predecessors, not ancestors. It seems probable that Eiffel himself – or, more precisely, Eiffel and his collaborators – first urged the idea of a 300 meter tower as the most audacious spike for the Exposition Tricolorée.

Even before the official announcement of a competition for the design of a 300-meter tower, Eiffel's company was at work on the plans. Maurice Koechlin, ÉmileNouguier, and Stephen Sauvestre, engineers and architects in Eiffel's employ, sketched out some preliminary plans for the tower, and presented them to their employer. He was pleased with what he saw, and so purchased the exclusive rights to his colleagues' plans. Thenceforth, the tower belonged to Eiffel. There was no question of the plan being carried forth by his subordinates, even though the idea in its first stages was undeniably their own. Only Eiffel has the financial resources, the professional reputation and the political leverage to carry the project to a successful completion.

Maurice Koechlin, Émile Nouguier, Stephen Sauvestre -- original designers of the Eiffel Tower

When the competition for the design of the tower was officially opened by the exposition committee, they were deluged with entries. Over 700 hopefuls submitted plans. Some were quite elegant; others, outrageous. One plan called for a tower in the shape of a watering can "that would be useful on sultry days." Perhaps the most grotesque – although admittedly faithful to the Centennial theme – was a 300 meter tower "in the form of a guillotine, to honor the victims of The Terror."[4] (See footnote for my rendering of what the “Guillotine Tower” might have looked like)

From the outset, Eiffel's plan encountered serious opposition and competition. When he presented his ideas for the 300 meter tower at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in 1884, detractors and supporters took sides, and the debate began. The most serious opponent of Eiffel's scheme was the prominent architect Jules Bourdais. Bourdais was an uncompromising proponent of traditional styles and materials. Along with Davioud, Bourdais had designed the Trocadero Palace, the major legacy from the 1878 exposition universelle. What a coup it would be, dreamed Bourdais, to garner the commission for the 300 meter tower: a crowning complement to the twin towers of my Trocadero Palace across the Seine!

Jules Bourdais, proposal for 300 meter tower

Like Eiffel, Bourdais had bought another man's idea, modified it, and submitted it as his own. The Bourdais tower would have been built of masonry and crowned with an electrical light beacon so powerful that Parisians would have been able to read a newspaper at midnight by its light in the Bois de Boulogne – several miles away. But most important, from Bourdais' point of view, was that his tower would be festooned with classical detail-work in stone.

In the ensuing debates with the supporters of Eiffel's plan, Bourdais scorned his rival's "vulgar" iron structure, asserted that his own stonework tower would cost only a fraction of what it would cost to erect the Eiffel Tower. Confronted with questions of the structural soundness of a 1000-foot stone structure, Bourdais turned evasive, and issued vague assurances that the structure would undoubtedly stand.

But the doubts remained. The great medieval cathedral builders, Eiffel argued, had pushed to the limits the height to which masonry could be raised. Only iron and steel had the tensile strength to rise higher. Furthermore, Bourdais had made no provision for the foundations of his masonry tower. It would rest directly on the ground. Eiffel, who had already constructed enormous arched bridges all over Europe, knew that a structure 300 meters high would need deep foundations and a carefully calculated system of stresses transfer to carry the enormous load deep into the earth. Furthermore, given the height of the tower, the force of the wind would be a major consideration – "It is the wind that determined the basic shape of my tower," [5] said Eiffel. All of these factors were lost on Bourdais, who thought exclusively in terms of traditional beam-and-load structures, and for whom ornamentation was basic value of architecture. For him, considerations of utility were secondary. Bourdais had, in fact, not even made provision for elevators in his tower.

In many respects, Bourdais's tower was a throwback to the conservative architectural thinking that had produced the Palace of Industry in 1855. There, too, the builders had covered up an iron and glass structure with a sheathing of stone arches, partly because of their fear that the iron would not adequately hold the massive sheets of heavy glass, and partly because the stonework gave them a chance to dignify the building with the dress of classical forms and ornamentation. The Bourdais tower carried within its design the same aesthetic: unadorned iron architecture cannot be beautiful.

When the examining committee met on May 12, 1886, Eiffel had already lobbied for his project and discussed it in detail with Edouard Lockroy, the new French Minister of Trade and head of the committee. All the proposals passed though this body and then a sub-committee. The 700-plus entries were narrowed down to nine, including those of Eiffel and Bourdais. On June 12, the committee announced that it had agreed unanimously that "the tower to be built for the 1889 exposition universelle must clearly have a distinctive character, and should be an original masterpiece constructed of metal. Only Eiffel's Tower satisfies these requirements fully."[6] Eiffel had won a resounding victory – a victory for him, a vindication of the aesthetics of engineering, a triumph of the present over the past. The first battle between iron and stone was over.

The Eiffel Tower tops them all: a comparison with the world's tallest structures: Strasbourg Cathedral on the far left, Cologne Cathedral on the far right

THE DEAL

Eiffel was awarded the contract for the tower, but he was dismayed to learn that the exposition committee would provide only 1,500,000 francs towards construction expenses – less than one-fourth the projected costs. Eiffel himself would have to finance his own revolution. With typical astuteness, Eiffel set up a series of shareholder organizations that would carry much of the costs, but leave him free of obligations if the tower proved as profitable as he hoped. Once the tower proved profitable – as it soon did – Eiffel was left in sole control of the profits from the Tower.

The key to Eiffel's plan was the agreement he had signed with a special exhibition committee. This contract gave to Eiffel the entire income from the tower for twenty years. In addition, Eiffel was allowed to construct an "Eiffel Pavilion," which featured in miniature some of Eiffel’s other engineering triumphs, such as the Garabit viaduct and a tiny working model of the Panama canal – "a marvel of patience and ingenuity, a veritable Chinese labor," remarked a writer for Le Figaro.[7] A 300-meter tower and a special pavilion exclusively devoted to his engineering achievements – it would be difficult to imagine a more effective advertising platform for Eiffel’s firm.

At the time they were negotiating with Eiffel himself, the exposition authorities deemed it prudent to save money at the outset by having Monsieur Eiffel bear the risks involved in the construction and operation of the tower. In the long run, though, the French government discovered that it had signed away a gold mine. Eiffel retrieved almost all of his costs in the first year after the opening of the tower. Subsequent profits from the tower – restaurant concessions, elevator tickets, plus the commissions that the tower's fame brought to his company – made Gustave Eiffel a very rich man.

"PARISIANS WILL LOVE IT"

"When it is finished, Parisians will love it,"[8] prophesied Eiffel as he began work on his 300 meter tower. But as soon as the plans were published, he was greeted by a chorus of groans and rage.

First came the cries of the people who lived in the neighborhood surrounding the tower. Every day people would come by and watch the construction work, gazing anxiously at the bolted beams that seemed to stretch skyward for miles. They also stared intently at the shadow that the tower cast on the ground. And the shadow moved in the wind! Surely this thing would be blown off its foundations in a strong gale! Eiffel was compelled to issue a statement in which he personally assumed full responsibility for any and all damage should his structure collapse.

But it was not the tower's potential demise that disturbed most critics: it was fear of permanence, the prospect of Eiffel's iron monstrosity dwarfing all the great Parisian monuments for years to come. A Committee of Three Hundred was formed – one member for each meter of the tower – consisting of some of the most illustrious names in French art and letters: artists Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Leon Gérôme, Adolphe Bouguereau, Antonin Mercié; writers Guy de Maupassant, Romain Rolland; musicians Jules Massenet, Charles Gounod; and, most telling of all, Charles Garnier, architect of the Opera House. The list of signatories to the protest is practically a roll call of all the outstanding proponents of tradition in literature, art, music and architecture. Listen to the tone of their plea, directed to Commissioner Alphand:

Honored compatriot, we come, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, passionate lovers of the beauty of Paris -- a beauty until now unspoiled -- to protest with all our might, with all our outrage, in the name of slighted French taste, in the name of threatened French art and history, against the erection, in the heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower.

After extolling the virtues of Paris as the loveliest city in the world, the Committee of 300 continues:

Are we going to allow all this beauty and tradition to be profaned? Is Paris now to be associated with the grotesque and mercantile imagination of a machine builder, to be defaced and disgraced? Even the commercial Americans would not want this Eiffel Tower which is, without any doubt, a dishonor to Paris. We all know this, everyone says it, everyone is deeply troubled by it. We, the Committee, are but a faint echo of universal sentiment, which is so legitimately outraged. When foreign visitors come to our universal exposition, they will cry out in astonishment," What!? Is this the atrocity that the French present to us as the representative of their vaunted national taste?" And they will be right to laugh at us, because the Paris of the sublime Gothic, the Paris of Jean Goujon, of Germain Pilon, Puget, Rude, Barye, etc. will have become the Paris of Monsieur Eiffel.

Listen to our plea! Imagine now a ridiculous tall tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black factory smokestack, crushing with its barbaric mass Notre Dame, Sainte Chapelle, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the dome of Les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all our humiliated monuments, all our dwarfed architecture, which will be annihilated by Eiffel's hideous fantasy. For twenty years, over the city of Paris still vibrant with the genius of so many centuries, we shall see, spreading out like a blot of ink, the shadow of this disgusting column of bolted tin.[9]

Cartoon of Eiffel personified as his tower

Eiffel was used to criticism, but never so vehement, and never from such a league of illustrious names. He replied in measured tones that engineers, too, have their standards of beauty no less worthy than those of the fine arts. Lockroy, who had headed the committee that chose Eiffel's design, replied in more sarcastic terms. Notre Dame and the Arc de Triomphe, he replied, could hold their own well enough. But he proclaimed himself "deeply distressed" for "the only part of the great city that is seriously threatened, this incomparable chunk of sand called the Champ de Mars, so worthy of inspiring poets and delighting landscape artists."[10]

Eiffel was reasonable, Lockroy feisty. But Eugene Melchior de Vogué, one of the most discerning writers on the 1889 exposition, replied in mythic sonorities to the critics of the tower. De Vogué imagines the Eiffel Tower to be endowed with the spirit of heroic vision as it speaks to the monuments of the past:

Old abandoned towers, no one listens to you any more. Surely you see that the poles of the world have shifted and that the world now turns on my iron axis? I am universal force disciplined by design. Human thought courses through my limbs. My brow shines with the light drawn from the source of all light. You are ignorance; I am knowledge. You enslave man; I free him. I know the secrets behind those miracles which terrified believers of old. My limitless power will remake the universe and will establish your paradise here on earth. I do not need your God, invented to explain the creation whose laws I comprehend. These laws are enough for me. They are enough for those souls I have wrested from you and shall never return."[11]

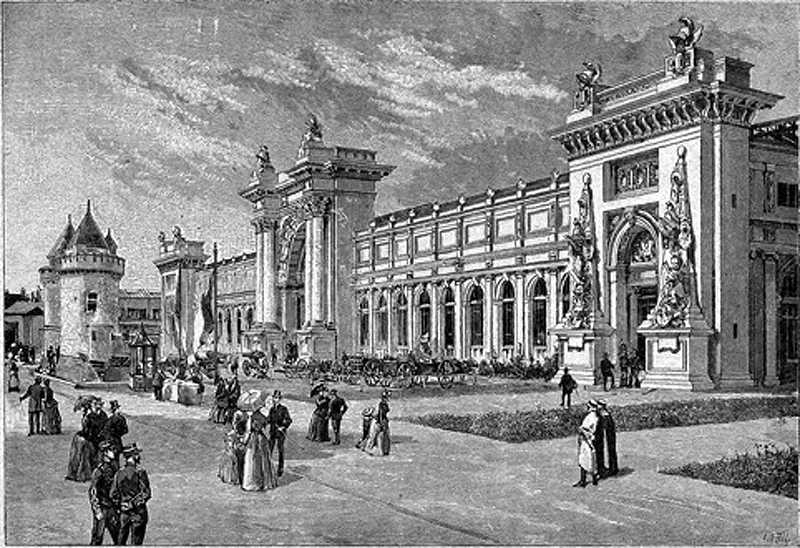

STONE VERSUS IRON: THE SECOND BATTLE

The war of words continued throughout the months of the exposition, and for the remaining years of the century. Discerning visitors could see the battle between stone and iron, modernity and tradition, continued in the buildings of the exposition. In strictly quantitative terms, tradition still dominated the field. With the exception of the Eiffel Tower and Dutert's Gallery of Machines, all the exhibition buildings, French and foreign, clung to the architectural vocabulary of the past. Oriental motifs could be found here and there, adding exotic flavor to a few European pavilions and complementing the structures of the near east, far east, and South America. But the pervading spirit behind the design of all these buildings was resolutely conservative. The revolution in architecture was only just beginning.

Dutert's Gallery of Machines (destroyed in 1906)

The leader of the reactionary forces at the 1889 exposition was Charles Garnier. His opera house, begun during the regime of Napoleon III and completed in 1875, was the consummate expression of the prevailing taste in architecture. Sumptuous in the grand style of the Second Empire, the opera house is still called "the cathedral of the right bank," the place where the cultured and wealthy attend the ritual worship of beauty in plush and gilded splendor. As we have seen, Garnier had signed the complaint penned by the Committee of 300. He believed that iron had its place in architecture, but as a servant, not a master. Metal should be dressed with stone, and stone should recall the glories of Greece and Rome, of Italy and France. Exposed iron in architecture, for Garnier, was an unforgivable lapse of taste. [12] For may years after the exposition, he railed against the Tower: "They have only erected the framework of this monument. It has no skin."[13]

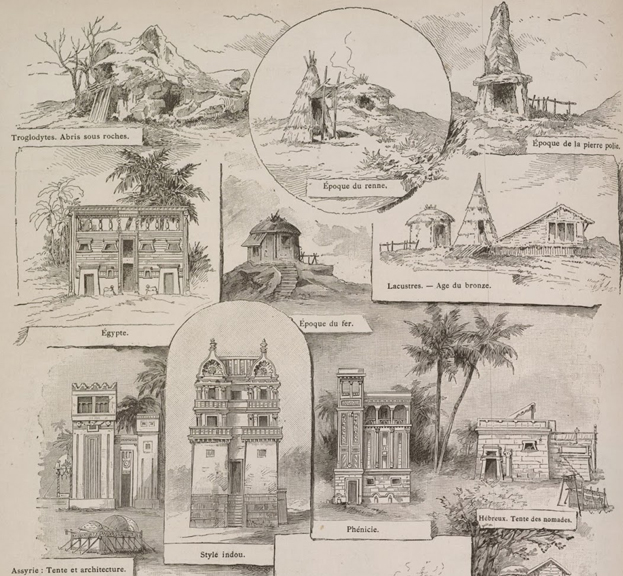

Garnier had other reasons to be outraged at the Tower. It dwarfed his own major contribution to the 1889 exposition, the History of Habitation, Garnier's homage to the archeological tradition that had flourished in world's fairs since 1855. Previous expositions had only displayed artifacts ranging from the past. But for the 1889 fair, Garnier had constructed entire dwellings of vanished eras: cave dwellings, reed huts, an Etruscan villa, a Persian mansion – thirty-three buildings in all. As C.L. Huard wrote, the History of Habitation was "a living book, both picturesque and instructive, of the dwellings of the entire human race."[14]

Drawings of some of the "History of Habitation" buildings (click HERE for a larger view)

Close by, in the Palace of Liberal Arts, a series of dioramas entitled "The History of Work and Ethnography" complemented Garnier's History of Human Habitation. These three-dimensional installments showed interior scenes of domestic life in past ages rendered with the same spirit of historical fidelity. Visitors could enter into the world of the past and have a sense of the living and working space of a stone-age arrowsmith or an ancient Greek potter. In 1889, "to instruct by pleasing" was still the watchword of the designers of the exposition universelle.

"Primitive bronze casting" diorama in the History of Labor section

Garnier had taken great pains to construct the ancient living quarters with historical exactitude, to give visitors a true sense of the ambient space created by thousands of years of human builders. He was the ultimate connoisseur of tradition, an architect with the soul of an archeologist. His own History of Habitation clearly showed that the human race had made changes and improvements in living quarters since the dawn of time. But when he faced the revolution of his own period, he scorned the upstart iron, and maintained that stone was the only material worthy of the noble style in architecture. His training and temperament gave him an appreciation of the artifacts of the past, but not of the spirit that gave rise to innovation.

"Quaint," "picturesque," "interesting" – Garnier's evocations of the past gathered polite praise from critics. But no matter where the visitor wandered among the buildings of the History of Habitation, the Tower loomed over them all. By November of 1889, all of Garnier's exhibit had been razed.

THE MAGIC CARPET

From Garnier’s theater of the studied past the visitor could enter the living realm of the exotic present by walking down to the Esplanade des Invalides, which housed the colonial section. "All Parisians, lifelong or temporary," wrote one contemporary observer, "are now possessed of a magical carpet. This carpet, a simple ticket of entrance, is the talisman that admits them to the country of dreams. Here you are transported, according to your caprice, from Cairo to the Americas, from the Congo to Cochinchina, from Tunisia to Java, from Annam to Algeria."[15]

In the center of the colonial section stood a pavilion designed by Sauvestre, the very employee of Gustave Eiffel who had sold his share of the original design for the Tower to his employer. The master constructs the 300 meter tower, the employee builds the colonial pavilion! Though Sauvestre's structure was not the lordly triumph of his employer, the colonial pavilion presided over the picturesque encampment with imperial authority. The colonials at the exposition surely recognized the inspiration for Sauvestre's pavilion: the governor's mansion at the center of the plantation, commanding a view of its subjects.

Since the exhibitors from the colonies lived in the Esplanade des Invalides for the duration of the fair, life there took on something of the rhythm of existence at home. The colonial quarter began to come to life in mid-morning. At 9:00 a.m., the streets were deserted. Only the crackle of frying rice or the pungent aroma of saffron disturbed the air. By 10:00, a few of the cafés began to open their doors. Soon visitors would stray up from the Quai d'Orsay, searching for the Tunisian restaurant where they could drink thick, rich coffee from an ornate cup. At lunchtime, the restaurants and cafés were crowded with fairgoers relishing a change from the refined fare of Parisian restaurants.

In the afternoon, the concerts, dances, and theatrical performances began. Crowds throng the theater in Cairo Street, where the Danse du Ventre delights and scandalizes even the scandalous Parisians.[16] The audience was sparser at the Javanese theater, where the dancers seemed to be idols brought to life. In the crowd you might have seen Claude Debussy, whose Petite Suite (1888) had so enchanted Parisian audiences and given them hope that the young Frenchman might bring a truly Gallic grace to the concert halls and thereby banish the domineering Teutonic cadences of Wagner. Soon after the exposition, colonial music, transformed and naturalized by Debussy, would create a revolution of its own in European concert halls.

Javanese dancers at the 1889 exposition

The Javanese dancers did more than provide Debussy with a kind of cross-cultural perspective. After the close of the exposition, they stayed in Paris and performed a number of times at theaters throughout the city. Javanese dancers were "in" throughout 1889 and 1890. They represented one of the first waves of exotic chic that would become a staple of Parisian social and artistic life for the next century. So audiences that came to hear Debussy’s revolutionary Afternoon of a Faun in 1894 had been well prepared for his novel harmonies. They had been listening to the Javanese orchestras and dancers perform, and were accustomed to accept – even to wax enthusiastic about – exotic harmonies in a concert setting.

During the first few months of the fair, the proprietors of the colonial pavilions were distressed that, when evening came, the crowds would desert the Esplanade des Invalides, to return home or to go back to the Champ de Mars and await the illumination of the fountains and the Eiffel Tower. How could even the belly dance compete with the splendor of the Eiffel Tower glowing against the night sky? So the colonial authorities met together, under the leadership of the Algerian and Tunisian Commissioners, and devised a plan. Every Tuesday there would be a colonial fête de nuit. All the inhabitants of the section would gather together and march in a parade through the Esplanade des Invalides.

Under the benevolent eye of invited French dignitaries, the colonial procession would pass by: first, the military – Senegalese cavalry, mounted on magnificent horses; Indian foot-soldiers, Chinese sharpshooters, Algerian infantrymen. Then followed the theatrical troupes: Annamites in frightening masks, veiled women dancers from Algeria, Javanese dancers in golden robes and hieratic poses. After the Javanese came a melange of pousse-pousse cars, palanquins, Congolese villagers and natives of New Caledonia. Finally came the great Tonkin dragon rising, diving, writhing along the processional path, preceded by merrymakers waving banners, parasols, and lanterns, banging on their sonorous gongs.

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Visitors were delighted. The Tuesday processional presented, in concentrated form, everything that Europeans hoped would flow from their colonial empires: exotic arts and marketable products, picturesque native culture, and military support. Furthermore, as one observer noted, the exposition consolidated these gains in an especially impressive manner:

From a political point of view, the experiences of our colonials at the exposition are uniformly excellent. Our natives carry away the impression that France is a rich and powerful nation. They recognize our moral superiority, and are less and less tempted to contest our authority.[17]

As if to impress the point conclusively, the French government placed the Pavilion of the Minister of War directly across from the colonial section in the Esplanade des Invalides. This massive structure, 200 meters long and 80 meters deep, was meant to impress upon the colonies that France was a nation with a long tradition of military might. The official pronouncements and the mottos on the presentation medals at the exposition extolled peace and fraternity. But the War Pavilion was a monument to the glory of combat. Memories of "The Terrible Year" were fading as the glory of colonial conquest shined brighter.

Pavilion of the Minister of War

Fronting the main entrance to the pavilion was a mammoth portal built in the style of a Medieval fortified castle, complete with drawbridge. Behind their twin parapets of this portal stood the main building, crowded with sculptures representing soldiers from past eras in France: Gauls and Franks; Medieval, Renaissance and 17th-century soldiers. Inside the building, the visitors could inspect either the historical exhibits or wonder that the display of new weapons – including gigantic Canet canons and a prototype of the machine gun. Paul Le Jeinsel, in writing an otherwise glowing report of the exhibits at the military pavilion, worried that France might be showing potential enemies her best weapons. "I sincerely hope," he wrote, "that if we have military secrets, tactical weapons, missiles or explosives, we have not put them on display here."[18]

Symbolically, the most striking part of the entire War Pavilion was the vestibule. Passing through the triumphal arch at the entranceway, visitors found themselves in an enormous foyer, with wide arcades leading to the left and right and a monumental, branched stairway directly ahead. There can be no question: the vestibule is a close imitation of Garnier's Opera House. M. Walvein, architect for the War Ministry, had fashioned France's military display in operatic terms. War, this building tells the visitor, is a stage – a splendid drama with a venerable history and a future made promising with technology.

As visitors rode their magic carpets across the Esplanade, the moral of the tale became clear: the Republic consolidates the Revolution with military might. France extends her glory, quashes insurrection abroad with the revolutionary advances in weaponry and armed hordes of colonial soldiers fighting under French leadership. The Exposition Tricolorée proclaims the Empire of the Republic.

SONS OF REVOLUTION

From a vantage point of more than 100 years after the event, it seems paradoxical that the French, who took such pride in their nation's colonial enterprise, would celebrate this empire in an exposition commemorating the very Revolution that freed the French people from oppression. It is also ironic that, at the Exposition Tricolorée, the nation with which France felt the closest kinship was the United States – itself a former colony. Of course, the French did not see themselves as the oppressors of their Asian and African colonies. France, as the self-proclaimed leader of civilization, was favoring them by bringing their governments and customs under the protection and encouragement of French culture.[19] After all, look at how well the United States had turned out, once they had incorporated the principles of the French Enlightenment into their Constitution!

The prestige of the United States was at a high water mark in France. Americans noted with pride that the United States garnered more medals than any other foreign nation at the 1889 exposition. Louis Comfort Tiffany won a grand prize for his works in silver. The University of California and Johns Hopkins University carried off gold medals for their photographic exhibits. Even American painters, who had scarcely received more than a passing mention at the previous expositions, did surprisingly well. John Singer Sargent and Gari Melchers won grand prizes for oil paintings – though Parisian art critic Lucien Huard was quick to point out the reason for the success of these American artists: "In effect, the American section can be considered more or less an annex to our decennial expositions, inasmuch as the most worthy of their artists are habitués of our annual salons. Mr. Sargent and Mr. Melchers, who won medals of honor, are in reality half-Parisians."[20]

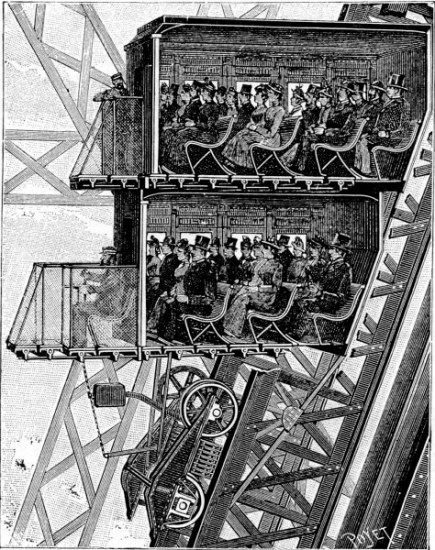

As the crowning acknowledgment of American ingenuity, Monsieur Eiffel declared that one of the four elevators in his tower would be built by the American Otis Elevator Company (the other three elevators were all constructed by French concerns). The Otis company showed a real flair for the dramatic as it demonstrated the soundness of its product to the French public:

The engineer of the American firm of Otis subjected the Otis lift to a final test before handing it over for public use. The lift was fastened with ordinary ropes, and this done it was detached from the cables of steel wire with which it is worked. What was to be done was to allow the lift to fall, so as to ascertain whether, if the steel cables were to give way, the brakes would work properly and support the lift. Two carpenters armed with great hatchets ascended to the lift; at a given signal, a blow cut the rope and the enormous machine began to fall. Everyone was startled, but in its downward course the lift began to move more slowly, it swayed for a moment from left to right, stuck on the brake, and stopped. There was a general cheering. Not a pane of glass in the lift had been broken or cracked, and the car stopped without shock at a height of ten meters above the ground.[21]

The Otis Elevator at work in the Eiffel Tower

Thomas Alva Edison repeated his triumph of the 1878 exposition. His inventions had undergone significant improvement in the intervening years; and it was recognized, in 1889, that his works were among the most innovative of the century. When Edison formally met with Gustave Eiffel in the latter's studio atop the Tower, people of France and the United States rejoiced to see the geniuses of the two sister republics together at the pinnacle of the Exposition Tricolorée.

Diorama of Edison and Eifel Meeting at the Exposition

Eiffel had good reason to be grateful for Edison's inventions. Every evening there was an illumination of the tower – the ancestor of the son et lumière spectacles that still delight visitors to Paris today. A series of powerful incandescent lights played over the surface of the tower and through the waters of the fountains at the tower's base. Visitors from every nation crowded together on the Champs de Mars and the Trocadero hill to catch a glimpse of this new form of spectacle. W.B. Franklin wrote with open admiration of these events:

It is a well-known fact that the French excel all other people in the art of ornamental illumination. Every detail connected with the illumination of the Exposition buildings, fountains, and grounds was elaborately worked out, so that it may easily be imagined what a source of interest and pleasure these nightly illuminations were to the hundreds of thousands of visitors, who waited long hours and bore every inconvenience of weather to see them. On many occasions the crowd was enormous, but it was always good-natured, and the simultaneous expressions of surprise, admiration, and delight that came from thousands of voices when the fountains were suddenly lighted up was an amusing and impressive feature of the scene. [22]

“To view San Francisco’s tribute to the Eiffel Tower featured at the California Midwinter Exposition in 1894, see footnote 24B below)

At the foot of the Eiffel Tower was another exhibit made possible by American inventiveness: the Telephone Pavilion. This structure served as the telephone communications center of the exposition, and the exhibits proudly showed the progressive extension of telephone lines from Paris to the outlying provinces. But the most successful section of the exhibit was the Auditions display. A series of telephones, each with two earpieces, was placed along one wall. Several miles away at the Opéra, ten telephone receivers lined up in front of the orchestra carried the sound of the music to the telephones at the exposition. Another set, located at the Comedie Française, likewise transmitted the actors' lines by telephone to the fair. After depositing 50 centimes, one could listen with the two earpieces to either the music or the actors. The result was a very convincing sensation of stereophonic sound. The left ear heard the instruments or actors on the left side of the stage, the right ear the performers on the right. If an actor cross the stage, the sound seemed to pass in front of the listener. "What intrigued everyone the most," wrote S. Fabvière, "was not only that they heard the orchestra or the actors perfectly, but that they even had the sensation of the physical placement of the actor in the scene. . . The idea was quite simple, but the effect was most extraordinary."[23]

Long-Distance Listening at the 1889 Exposition

The American presence at the 1889 exposition was not limited to mechanical or electrical inventions, or to the new (even if half-Parisian) competence in the fine arts. There were other exhibits that seemed to French critics as the products of a nation not quite grown up. One critic noted with amusement that the same nation that had given the world the telephone, the telegraph, and the phonograph could exhibit, with apparently equal pride, a series of heads of American presidents executed in meerschaum. As he was trying to recover from the idea of Americans smoking Jefferson or Lincoln, Arny spotted a gigantic pipe in the shape of a buffalo head, "whose stem was notched, checkered and betoothed like a Gothic spire. It was very well-executed; but only Gargantua could have smoked it." The pipe, he learned had been promised to Buffalo Bill, who had hitched his horse to the Eiffel Tower as he toured the exposition.

Monstrous buffalo pipes, Ulysses S. Grant stuffed with tobacco -- what would these transatlantic sons of liberty think of next? Why, a Venus de Milo sculpted entirely out of . . . chocolate! This delectable example of American taste was much larger than her marble original and weighed in at a ton and a half. The dumbfounded critic recovered his wits long enough to observe that "she is inexpressibly American." (What a wealth of French value judgement lies in that simple observation!) Unfortunately, after several warm Parisian summer days, "the poor Venus had lost some of her elegance of form. No, chocolate is decidedly not the sculptural material of the future."[24]

Chocolate sculptures alongside the phonograph, Buffalo Bill's buffalo head pipe by the Singer sewing machines – no wonder that European intellectuals had such difficulty in assessing American culture. We have already seen the stinging reference to American business culture in the attack by the Committee of 300 – "Even the commercial Americans would not want the Eiffel Tower" – implying that taste in the United States leaves a great deal to be desired, even if it not so depraved as to lust after the colossally ugly.

In fact, the United States occupies something of a special place in the esteem of French journalists and intellectuals in 1889. Americans are regarded as a kind of third estate, somewhere halfway between the countries one must take seriously – England, Italy, and other European nations – and the colonies, which one values precisely insofar as they accept European civilization and supply European nations with either raw material and/or interesting examples of native culture. Not until the 1900 exposition will the United States demand – and receive – its place as an equal to the nations of Europe. (24A)

RETROSPECTIVE

The Exposition Tricolorée was more than just another excuse for Paris to play host to the world. More than any other event in the recent history of France, the 1889 fair gave the nation a chance to think over and to assess its own past. In the 100 years since the Revolution, France had been the stage for some of the most destructive and most creative acts in the history of the human race. Now, in 1889, the destruction seemed to be over. Peace and prosperity had reigned for almost two decades. The Revolution was bearing its finest fruits at last.

This quality of patriotic reflection could be seen most clearly in the fine arts retrospective at the Palais des Beaux Arts. Here, visitors could see gathered together the choicest works of French art painted or sculpted since the fall of the Bastille. In their own lifetimes, the reception of the works of David, Millet, Gericault, Delacroix, Ingres, and Manet was often stormy. But in the exposition exhibit hall – with its "calm serenity of a temple," as art critic Paul Mantz wrote – the assembled masterpieces attested to the continuity and unity of French art. Here were the artists, as Alfred Picard wrote proudly in his final commission report, who "had given France her incontestable superiority in the arts."[25]

But there was yet another puzzling irony of the 1889 exposition, which so successfully celebrated the centennial of revolution with a revolutionary iron tower: the Impressionists were excluded from the Exposition Tricolorée. Antonin Proust, President of the Exposition, was a well-known supporter of the Impressionists. But even his influence was not enough to gain admittance for the works of these revolutionaries. Not until 1900 would their works appear with honor inside the gates of a Parisian international exposition. As if continuing the outsider tradition of Courbet and Manet, and in defiance of traditional canons of French art so triumphantly displayed at the Palais des Beaux Arts, Paul Gauguin exhibited his works at the Café Volponi during the summer months of 1889. [26]

Only in one instance did an outsider – one scorned by the French institution of academic artists and critics – succeed in placing a work in the French fine arts exhibit. Several years before, Auguste Rodin had been accused of cheating by using a life cast to execute his Age of Bronze. Rodin was cleared by Edmond Turquet, deputy Minister of Fine Arts under Antonin Proust. The charge was leveled once again at St. John the Baptist. This time the government not only vindicated Rodin: in clear defiance of the Academie des Beaux Arts, it exhibited this work among the masterpieces of French sculpture at the exposition. Rodin himself served as a juror for the exposition. Even in the conservative fine arts, revolution was winning out.

THE LEGACY OF REVOLUTION

After the closing ceremonies on November 6, the world applauded Paris and France for the achievements of the Exposition Tricolorée. For many visitors, the 1889 Exposition itself gave ample evidence that he French were the greatest people of modern times. As W.B. Franklin wrote in his official report to the members of the United States Congress:

The perfection of the administration of the Exposition, the magnificent show of industrial and agricultural products, the exhibits of the fine arts, which have never been equaled, the splendid works of engineering and agriculture which are shown in all parts of the grounds, the intelligent exhibits of the history of work, the colonial exhibits, in fact, everything connected with the Exposition, convinces an intelligent observer that the nation which could thoroughly organize so grand a work must at least be abreast of all modern nations in works of industry and art, and in the ability to organize and utilize the brains and muscles of its people.[27]

The Republic had succeeded. The Revolution was vindicated, and its monument, the Eiffel Tower, would become the very signature building of Paris herself. But the forces of tradition watched and awaited their chance for one final act of vengeance:

It is 1910, and the Champ de Mars is crowded with the dust and debris of destruction. Workers have just pulled down Dutert's Palace of Machines, one of the glories of metal architecture at the 1889 Exposition. The engineers are outraged; the traditionalists are smiling with satisfaction. This building, along with Eiffel's Tower, were the outstanding exemplars of iron architecture at the Exposition Tricolorée. For some experts, the Gallery of Machines was even more revolutionary than the Eiffel Tower. The beams of the Tower still supported a horizontal load: the observation platforms. In the Gallery of Machines, as architectural historian Siegfried Ghiedion has noted, "the last hint of the antique column has disappeared. It is impossible to separate load and support." [28]

Destruction of the Galerie des Machines, 1910

Why was this innovative building destroyed? Because, according to its enemies, the Palace of Machines spoiled the view of Les Invalides, one of the masterpieces of ancien régime architecture, whose lordly dome rises up over Napoleon's Tomb. The vast interior of the Gallery of Machines was impressive from an engineer's point of view. But the building's exterior lacked sufficient traditional elegance to save it from destruction. Its only purpose would have been to house temporary exhibits – and this function, in 1900, belonged to the Grand Palais. So the Gallery of Machines went the way of so many other near-masterpieces of exposition architecture in Paris.

But in spite of the fate of the Gallery of Machines, the revolution had won out. Joining base to summit and earth to heaven, the Tower remained, even after Eiffel's 20-year contract expired. [29] The Eiffel Tower not only enhanced the skyline: it gave the people of France a heroic monument to the vindication of Revolution. Its creed might be taken from the words of the Gabriel Vicaire's prize-winning song composed for the Exposition Tricolorée:

Oh ye who cry out, I am sweet France;

I have awakened Destiny from deep slumber,

I have destroyed the old laws, I bring hope;

The star of morning shines on my brow.[30]

NOTES

1 The author "Lissagaray," in La Bataille, Monday, August 19, 1889, page 1

2 "Les 13,000 Maires," in Le Pilori, August 25, 1889

3 To be fair, we should note that the commissioners had not planned on preserving the tower. As we shall see, the most famous of all world's fair buildings won immortality only through the adroit maneuvering of its creator. It would not be until the 1900 exposition universelle that the exposition commissioners consciously set out to create buildings that would outlive the fair itself and become permanent monuments of the city.

4 Philippe Bouin and Christian-Philippe Chanut, Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1980), page 118

Here’s my rendering of what the “Guillotine Tower” might have looked like:

5 Quoted in the documentary film, The Unknown Eiffel (1975)

6 Quoted in Eiffel's La Tour Eiffel vers 1900 (Paris, 1902), page 9

7 Le Figaro, August 7, 1889

8 John Allwood, The Great Exhibitions (London, 1977), page 77

9 Printed in Le Temps, February 14, 1887

10 Quoted in F. Poncetton, Gustave Eiffel (Paris, 1939), pp. 168-169

11 Melchior de Vogué, Remarques sur l'Exposition (Paris, 1889), pp. 24-25

12 Henri Loyrette, in his admirable study of the tower Gustave Eiffel, (New York, 1985), draws a fascinating and convincing parallel between Garnier's disparagement of iron with Charles Baudelaire's earlier (1859) disdainful treatment of photography.

13 Charles Garnier, "Le diner de l'Ecole," L'Architecture, December 17, 1892, p. 589

14 Livre d'Or de l'Exposition (Paris, 1889), page 3

15 G. Lenotre, L'Exposition de Paris 1889, Volume I, No. 19, page 151

16 The Franco-Egyptian commissioners clearly reckoned both Cairo Street and the belly dance a success. Both features of the Egyptian exhibit would be exported in 1893 to Chicago and in 1894 to San Francisco.

17 E. Monod, L'Exposition Universelle de 1889: Grand Ouvrage Illustré (Paris, 1890), Volume II, page 139

18 Livre d'Or de l'Exposition, ed. Huard, Vol I. (Paris, 1889), page 337

19 Commenting half a century after the event, historian Raymond Isay accurately interpreted the symbolism of the military and colonial pavilions:

Along with the military exhibits, the colonial section presents in striking fashion one of the two complementary faces of the French government and nation. In effect, republican France, such as it was from this time down to 1914, presents a double character. On the one hand, France is, and desires to be, the educator, the benefactor, the dispensor, to all people young and old, of intellectual and material nourishment, distributor of enlightenment and bread. It is in this profoundly-felt feeling that we encounter, in the expositions of 1889 and 1900, the sections devoted to public instruction and social economy. But on the other hand, France states clearly that she will not renounce her mission of world-wide imperialism. This mission, its clear statement and its sense of justification, can be found in the exhibits of the colonies and the military, both on the Esplanade des Invalides.

– Panorama des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1937), page 186

20 Livre d'Or, page 358

21 Scientific American, June, 1889

22 The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1889-1890, Vol, 38 (Washington, D.C., 1893), page 26

23 Livre d'Or, page 475

24 ibid., page 485-486

24A It took the mind and talent of Rosa Bonheur to recognize the “wild west” nobility of an American original such as "Buffalo Bill Cody,: as evidenced in her 1889 portrait:

Rosa Bonheur’s portrait of Buffallo Bill, Paris, 1889

24B The Eiffel Tower at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris and the Bonet Electric Tower at the 1894 Calidfornia Midwinter International Exposition in San Francisco:

25 "Exposition Universelle de 1889: La Peinture Française," La Gazette des Beaux Arts, July 1, 1889, page 27

26 See Jean-Luc Daval, "Gauguin and the 1889 World's Fair," in Modern Art, The Decisive Years, 1884-1914 (New York, 1979), pp. 64-65. Gauguin and his friends named themselves the "Impressionist and Synthetist Group," and opened their show at the Café Volponi in May of 1889.

27 The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1889-1890, Vol, 38 (Washington, D.C., 1893), page 27

28 Siefreid Ghiedion, Space, Time, and Architecture, page 273

29 In spite of the 20-year contract, which guaranteed Eiffel the revenues from the tower, there were persistent attempts by antagonists to have the tower demolished. One group of his supporters, the Association Française Pour l'Avancement Des Sciences, issued in 1903 a "Protestation contre la proposition de démolition de la Tour Eiffel. See Documents relatifs à la conservation de la Tour Eiffel (Paris, 1903)

30 In L'Exposition de Paris, June 8, 1889, page 115 ff.

STATISTICAL APPENDIX

Opening Date: May 6, 1889

Closing Date: October 31, 1889

Size of Site: 235 acres

Official Attendance: 28,100,000 (estimated actual attendance: 32 million)

Exhibitors: 6,000+

Expenses: 60,000,000

Receipts: 52,000,000

Profit to Government: 8,000,000 francs

Top Officials:

Antonin Proust, President

M. Alphand, Directeur Général des Travaux

Georges Berger, Directeur Général de l'Exposition

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allwood, John. The Great Exhibitions (London, 1977).

Bouin, Philippe and Chanut, Christian-Philippe. Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1980).

Daubin, Maurice. "Le palais des macines à l'Exposition Universelle," Journal de la Jeunesse, 1889, Volume 2.

Eiffel, Gustave. La Tour Eiffel vers 1900 (Paris, 1902).

L'Exposition de Paris (1889), Publiée avec la collaboration d'écrivans spéciaux, bound as two volumes (Paris, 1889).

Garnier, Charles. "Le diner de l'Ecole," L'Architecture, December 17, 1892.

Henard, Eugène. "L'Architecture en fer à l'Exposition de 1889," Le Génie Civil, July 6, 1889.

Huard, Lucien. Livre d'Or de l'Exposition (Paris, 1889).

Isay, Raymond. Panorama des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1937).

Lenotre, G. L'Exposition de Paris 1889, two volumes (Paris, 1889).

Loyrette, Henri. Gustave Eiffel, (New York, 1985).

Mantz, Paul. "Exposition Universelle de 1889: La Peinture Française," La Gazette des Beaux Arts, July 1, 1889.

Monod, E. L'Exposition Universelle de 1889: Grand Ouvrage Illustré, two volumes (Paris, 1890).

Picard, Alfred. Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1889 à Paris. Rapport par M. Alfred Picard (Paris, 1891-96).

Poncetton, F. Gustave Eiffel (Paris, 1939).

Vogué, Melchior de. Remarques sur l'Exposition (Paris, 1889).

Wilson, E.B., general editor. The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1889-1890, Vol, 38 (Washington, D.C., 1893).