From the Diary of Father Vicente de Santa María (1775)

Father Santa Maria’s diary, written a year before the founding of the Mission Dolores, reveals to us both a European’s perception of the Ohlones who lived on the land that would become San Francisco, as well as the character of the religous forces that came to the new world to convert the natives to Catholic Christianity.

Father Santa María served for a time at the Mission Dolores, but was soon transferred by the mission’s founder, Junípera Serra, who intimated that Father María “is not exactly one for being kept in hand.” His removal was unfortunate, since Father Santa María was one of the rare Spaniards who bothered to learn the Ohlone’s language.

Father María’s diary gives us a clear look into his heart. Though he felt a civilized Christian’s superiority to the “savage heathen,” he genuinely liked, and occasionally even admired, the quick intelligence of the Native Americans he encountered. He was one of the first, and one of the last, Europeans to feel anything like a kindred humanity with the Ohlones of the Bay Area.

Mistrust

“On that day the captain, the second sailing master, the surgeon, and I, with some sailors, went ashore. Three Indians who had been sitting for some time at the top of the slope that came down the shore, as soon as they saw us landed, fled from our presence without pausing to heed our friendly and repeated calls.

“Accompanied by a sailor, I tried to follow them in order to pacify them with the usual gifts and to find out what troubled them. We got to the top of the ridge and found there three other Indians, making six in all. Three of them were armed with bows and very sharp-tipped flint arrows.”

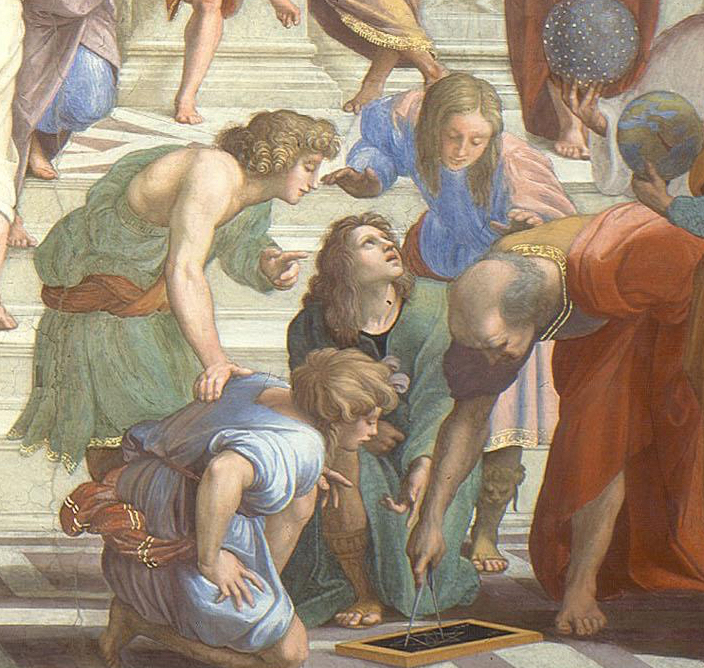

Ohlone hunters, rendered by Louis Choris in 1816

Rapprochement and Fear

“Although they at first refused to join us, nevertheless, when we had called to them and made signs of good will and friendly regard, they gradually came near. I desired them to sit down, that I might have the brief pleasure of handing out to them the glass beads and other little gifts I had had the foresight to carry in my sleeves. Throughout this interval they were in a happy frame of mind and made me hang in their ears, which they had pierced, the strings of glass beads that I had divided among them…"

“When I had given them this pleasure, I took it into my head to pull out my snuffbox and take a pinch; but the moment the eldest of the Indians saw me open the box he took fright and showed that he was upset. In spite of all my efforts I couldn’t calm him. He fled along the trail, and so did his companions, leaving us alone on the ridge.”

An Eighteenth-Century Spanish Snuff Box

(Click the image for a lightbox view)

Iconoclasm

[Father Maria is walking in the hills of San Francisco and comes upon a large rock with some “droll objects” in its cleft:]

“These were slim round shafts about a yard and a half high, ornamented at the top with bunches of white feathers, and ending in an arrangement of black and red-dyed feathers imitating the appearance of the sun.

“At the foot of this niche were many arrows with their tips stuck in the ground as if symbolizing abasement. This last exhibition gave me the unhappy suspicion that those bunches of feathers representing the image of the sun (which in their language they call gismen) must be objects of the Indians’ heathenish veneration; and if this was true -- as was a not unreasonable conjecture -- these objects suffered a merited penalty in being thrown on the fire.”

Sun Feathers

Commiseration

“No sooner were signs made to the women to approach than many of them ran up, and a large number of their small children, conducting themselves toward all with the diffidence the occasion demanded. Our men stayed longer with the little Indians than with the women, feeling great commiseration for these innocents whom they could not readily help under the many difficulties that would come with the carrying out of a new and far-reaching extension of Spanish authority.”

Diorama of the Mission Dolores as it might have appeared in 1799

Song

“ I landed and remained alone with the eight Indians, so that I might communicate with them in greater peace. The landing boat went back to the ship and at the same time they all crowded around me and, sitting by me, began to sing, with an accompaniment of two rattles that they had brought with them. As they finished the song all of them were shedding tears, which I wondered at, not knowing the reason. When they were through singing they handed me the rattles and by signs asked me to sing. I took the rattles and, so please them, began to sing the ‘Alabado’ (although they would not understand it), to which they were most attentive and indicated that it pleased them.”

To hear an Ohlone tune on a modern flute, click HERE