THE PLANNERS OF the Midwinter Exposition believed that San Francisco's first world's fair should do more than house exhibits and provide amusement. A serious exposition, they felt, should also sponsor serious discussions of ideas by bringing together respected authorities in the fields of economics, politics, religion, literature, education and science. Such events, following the precedent of previous world's fairs, were called "congresses." Millionaire patron of the arts and future San Francisco mayor James Phelan was chosen president of the Midwinter Exposition Congresses Committee, whose task was to organize and promote discussions that would "advance the cause of Progress in human endeavor.”

Like the buildings and exhibits of the exposition, the congresses -- some of which were held on the fairground, some in downtown San Francisco -- were eclectic and world-wide in scope. Also like the buildings, many of the congresses devoted sessions to the specifically Californian setting of their subject. Just as each of the major buildings at the fair blended architectural motifs from various cultures, so the congresses sought a regionally-based, European inspired, global perspective in the range of topics they considered. Economists discussed "The Market for California Breadstuffs," as well as "Monetary Affairs in the United States" and "England's Relation to Monetary Affairs in India." The Literary Congress opened with a passionate defense of California regional literature; then came sessions devoted to the entirety of English and American literature; at the conclusion, auditors heard a scholarly paper on "Prehistoric Malayan Literature.”

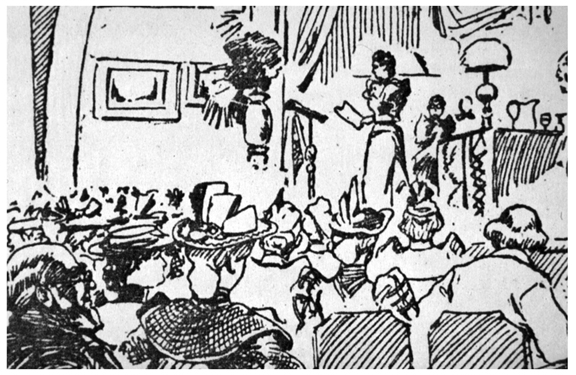

But the liveliest of the exposition meetings was the Woman's Congress. The fair organizers had already encountered some strong sentiments from women about their lack of presence on the planning committees. "The Midwinter Fair people have run afoul of the woman question thus early," commented a writer for one of the Sacramento newspapers. "Certain sex-conscious women are howling because no provision has been made for a board of `lady managers,' and for a distinctive women's department. “(22) Since the Chicago exposition had an entire Woman's Building, designed by a woman architect and devoted entirely to feminine exhibits, it is likely that local feminists felt that the Midwinter Fair should do no less in support of women’s issues.

THE WOMAN'S CONGRESS AT THE MIDWINTER FAIR

But the protests produced no Board of Women Managers and no Woman's Building. Local supporters of such causes had to be content with a congress. Discussions were centered around those activities which, in the world of the 1890s, constituted acceptable activities for women: education, charities and missionary work, and the decorative and pictorial arts. However, as the discussions progressed, topics ranging from educational reform to the immigration question to the disadvantages of female costume in the workplace to women's suffrage were hotly debated. A budding militancy pervaded many of the meetings, especially in the panel devoted to the topic of exclusion of women from the business world. But the very liveliness of such debates led the fair directors and the local newspapers to count the Midwinter Fair Congresses a resounding success. Certainly the Woman's Congress was the first major forum in which San Francisco women were able to begin to engage their male counterparts as equals in sustained and serious discourse on significant social issues.

Women certainly made their presence felt at the exposition, whether as county officials, Midway performers, concession employees, Gum Girls, medical attendants, or participants in educational exhibits and congresses. Renowned American sculptor Harriet G. Hosmer exhibited her “Queen Isabella of Castile” (displayed the year before at the Chicago exposition) in the Fine Arts building at the Midwinter Fair. Florence Lundbourg, local painter and contributor to the famed bohemian journal The Lark, contributed a pastel entitled “Study of an Oak,” one of many works by California women artists at the Midwinter Fair. Special days were celebrated for such female organizations as the Teachers’ Congress, Girls’ High Schools, the Catholic Ladies Aid Society, the Native Daughters of the Golden West, the Daughters of Rebecca, Mills College, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the San Francisco Federation of Women. In addition, such groups as the Women’s Pacific Coast Press Association and the Woman’s Congress of Missions used the exposition as the site for their annual meetings.

Women were also prominent participants in several of the Midwinter congresses. Well-known scholar of Persian literature Elizabeth Reid, for example, presented a major paper at the Congress of Religion entitled “Christ not Krishnax (sic).” At the Education Congress Lillie J. Martin spoke on “The Highest Education of Women.” And at the initial meeting of the Temperance Congress, held privately in conjunction with the exposition, the first two addresses were delivered by women: Mrs. B. Sturtevant-Peet and Mrs. S.C. Sanford of Oakland.

The lover of wisdom or lively debate could choose from a large variety of offerings at the Midwinter Fair. Some, like the meetings of the American Medical Association and the California Teachers' Association, were the regular annual meetings of these associations held in conjunction with the exposition. Others, like the Dental Congress, were scheduled especially for the Midwinter Fair. Still others, while not receiving exposition sanction, capitalized on the crowds of visitors to patronize their meetings. One of these unsanctioned events was the Temperance Congress, held in a tent erected at Seventh and Mission Streets in the city. The mood of these gatherings was often fervently missionary, featuring impassioned rhetoric and tearful confessions from reformed drinkers. But the revivalist tenor of the Temperance Congress was at least partially balanced by the appearance of some distinguished speakers, including David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University.

Other groups that might not have gained a foothold in the exposition by themselves managed to get a hearing under the auspices of the Religious Congress. Most of the meetings held in the Religious Congress were not controversial and confined themselves to topics such as "The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man," "Historic Theism," and "The Reciprocity of Religion and Art." Some speakers, though, pushed their own agendas. "Christ Not Krishna' devoted itself to an exposition of the superiority of Christianity over "Hindooism." Another lecturer spoke on "The Church and Municipal Reform" and raised the possibility of creating a national church in the United States.

The profusion of congresses bespoke a parallel interest in the publishing an energetic little journal, The Lark, which would achieve national circulation and critical praise. Frank Norris was hard at work on McTeague perhaps the definitive novel of San Francisco during those years, and one of the great social novels of nineteenth century America. Sculptures began to line Market Street-an anticipation of the City Beautiful movement that came to the city soon after the turn of the century. Opera, symphonic music, the theater, and fine publishing houses thrived in a San Francisco eager to take its place as a cultural leader among American cities.