Aerial View of the 1798 Exposition Grounds

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

The first exposition grounds, with the Temple of Progress in the center and a Montgolfier balloon overhead

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

L'Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française

Paris, 1798

by

Arthur Chandler

Reprinted and revised from World's Fair, Volume X, Number 1, 1990

For discussions of the following French industrial expositions, see:

The Napoleonic Expositions: 1801, 1802, 1806

Expositions of the Restoration: 1819, 1823, 1827

Expositions of the July Monarchy: 1834, 1839, 1844

Exposition of the Second Republic: 1849

Introduction

If it is true that "of all events in recent history, only wars have had more dramatic influence than World expositions upon the expression of civilisation,"(1) then the first industrial exposition, held in Paris in 1798, deserves a high place of honor in the annals of human culture. This exposition is the forerunner of the hundreds of national and international industrial expositions that have been staged all over the world, from 1851 down to the present. Born of a confluence of tradition and revolution, the exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française set in motion one of the great rituals of Progress — the belief in the application of technology for the improvement of the quality of life — that distinguishes Western civilization.

Rituals of Revolution

As the tumultuous final decade of the eighteenth century drew to a close, France was still in upheaval. Though the executions of the first years of the 1790s were fading into memory, new violence threatened to destroy the fledgling Republic. The coup d'etat of 1797 put the radicals back in power, sending the losers into Switzerland and South America. While Royalists and Jacobins battled each other and other factions, General Bonaparte, fresh from glorious and profitable victories in Italy, embarked on his Egyptian odyssey, vowing to bring the Middle East under French sway. During one twelve month period from 1797-1798, the Directorate, in an effort to purge the power of the Church from the lives of the people, deported over a thousand priests from France. Talleyrand, that protean Minister of Foreign affairs who weathered all the storms of monarchy and republic, sensed the coming turbulence and retired to his estates to enjoy his spoils and await the outcome of events.

With the banishment or execution of priests and nobles, the people of France had gained their freedom from their ancient oppressors. But the leaders of the Revolution realized that the old institutions could not be swept away without leaving a void in the lives of the people. In a gesture partly spontaneous and partly calculated, the leaders of the new regime encouraged the establishment of new rituals: festivities that would celebrate and solidify the achievements of the revolution.

The first of the major new festivals was the Fête de la Fédération, held on July 14, 1790. Laborers and shop-owners, men and women from virtually all walks of Parisian life, assisted in the labors of constructing the grandstands and platforms on the Champ de Mars, and decorating the Place de la Bastille and the Champs-Elysées with banners and lanterns, pavilions and swags that would brighten and dignify the ceremonies. There were speeches, military exercises, music and balls that lasted far into the next morning.

Fête de la Fédération, from a watercolor by Antoine-Jean Duclos

During the next decade, the changing governments of France sponsored a dozen major, and dozens of lesser festivals: the Festival of Law (1792), the Festival of Unity (1793), the Festival of Reason (1793), the Festival of the Supreme Being (1794), the Festival of Victory (1796), the Festival of the Foundation of the Republic (1796), the Festival of Liberty (1798). To the cynic's eye, all these contrived ceremonies might appear to be no more than the entertainment program of the government's bread and circuses for the unruly Parisian mobs. But subsequent historians have seen a good deal of wisdom in these ad hoc rites. Each of the festivals gave those in power an opportunity to reinforce the new values that they were trying to teach. In a land where there were still many royalists and royalist sympathizers, a festival that celebrated the virtues of the republic could serve as a powerful restorative elixir for those whose revolutionary fervor might be on the wane. A ceremony commemorating the fall of the Bastille — the one ceremony of this period that is still observed in France today — united all the people in a rejoicing over the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic. In later years the event also reminded them that they, as a people, had killed their king and queen to make this republic a reality, and that a spirited celebration of the Republic was better than a fearful remorse over regicide.

The suppression of the church presented the revolutionary government with a more difficult problem. Kings and nobles might be guillotined or exiled in a spirit of self-righteous wrath. But the hold of the church on the morals and conscience of the French nation was far stronger, much more difficult to root out and replace. It was Robespierre who made the most vigorous attempt to replace the old faith with a new creed, one more consonant with the dictates of reason and the needs of the republic. He proclaimed a festival in honor of the Supreme Being, and called upon Jacques-Louis David, the greatest living French artist, to design and organize the spectacle.

La Fête de l'Etre suprême watercolor by "Naudet"

On a lovely spring day in June, 1794, Parisians waved tricolor flags and bedecked themselves with garlands of fresh flowers as they marched in parade from their neighborhoods to the gardens of the Tuileries, close by the Louvre. Robespierre and other dignitaries were seated on a grandstand labelled "the Pavilion of Unity," before which stood a huge oakum statue labeled "Atheism" and four smaller ones representing Ambition, Discord, Egotism, and False Simplicity, on which the sign "Sole Foreign Hope" was displayed. Robespierre delivered a fiery speech, comparing the perversion of atheism with the enslaving superstitions fostered by priestly religion. The orchestra then played a joyful symphony, after which Robespierre, armed with a Flame of Truth, approached the monument representing the monster of Atheism and set fire to it. Godlessness went up in flames, revealing a fireproof statue of Wisdom beneath (This last touch did not come off quite as planned, since Wisdom emerged with a face blackened with soot and ashes).

Wisdom Revealed

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

After this rousing combustion, the crowd and the leaders separated into divisions, each person joining his or her neighbors from their home neighborhood. As the procession moved to the Champ de Mars, thirty six maidens danced around the parade, led by members of the Convention carrying the "Fruits of Nature," and concluded by a host of singing blind children. Here the participants found an artificial mountain surmounted by the Tree of Liberty. At the very top of the tree were the Tricolor flag and Phyrgian cap of Liberty, the two most evocative symbols of the Revolution. More military music, anthems, and artillery firing punctuated the festivities. Observers called the Festival of the Supreme Being "a very beautiful fete," "grand," and even "sublime." Many historians consider this event the peak from which later festivals declined. (2)

"A Striking and Novel Spectacle"

It was Robespierre, author of the Festival of the Supreme Being, who later suggested that the government should sponsor a whole series of festivals, including one which would pay homage to industry. He fell victim to the guillotine before he could realize his project. But four years later, Robespierre's dream was revived. According to one contemporary observer, Anthèlme Costaz, this is how it came about:

The idea for holding industrial expositions came in 1797, as the Executive Directory planned its celebrations for the anniversary of the foundation of the Republic. They wanted something striking; and so Minister of the Interior François de Neufchâteau convened a meeting of distinguished men to discuss the matter. There was a good deal of disagreement among them, but all concurred that it would be redundant simply to have the kind of dances and Maypoles common at other such events. What was needed was a striking and novel spectacle. One person suggested giving the festival the ambience of a lively village fair, only more grand. Someone else suggested that even more enjoyment could be had by adding an exposition of painting, sculpture, and engraving to the dances and Maypoles, chariots and horse races. The discussion made Minister Neufchâteau realize that if popular entertainment could be staged with such seriousness, it would be well to give the mechanical arts a similar advantage. His proposal met with universal and enthusiastic approval because it would produce a truly new and striking spectacle. (3)

Armed with the approval of the Directory, on the 9th of Fructidor, Year VI (the 26th of August, 1798), François de Neufchâteau, Minister of the Interior for the French Republic, issued a circular to all government officials, calling for a new kind of festival to commemorate the founding of the new government:

Citizens:

At the time when the anniversary of the foundation of the Republic. . . is about to remind all Frenchmen of the triumphs and glorious memories of the great events that made it all possible, are we to forget the useful arts that contribute so forcefully to our prosperity?

The government must have particular care to protect and encourage the useful arts. It is with this goal in mind that it has decided to hold, in conjunction with the festival of the first of Vendémiaire, a new kind of spectacle: a public Exposition of the products of French industry.(4)

François de Neufchâteau

We should pause over the use of the word "spectacle," a term employed by both Neufchateau and Costaz. For many centuries, the term has a precise and glorious set of connotations. A spectacle was a common event throughout Europe — especially Italy and France — from the Renaissance down into the eighteenth century. A spectacle could include public entertainments, tournaments, and triumphal processions.

Public entertainments were common in the trade fairs throughout France since the Champagne fairs of the 12th century. At Troyes and Provins, and perhaps Saint Denis near Paris, “the village trade fairs” alluded to by Costaz were commercial ventures enlivened by celebration: "The streets were thronged with the crowds that danced and joked and sang with the troubadours. At the end of the revelry the armed sergeants of the fair... marched through the streets with flaring torches, followed by bands of fiddlers."(5) As we shall see, this aspect of the village fair was present in part at the ceremonies surrounding the first industrial exposition.

Tournaments suggest jousts to the modern reader; and in fact, these were once the most exalted form of competition to be held on "the fair field of honor" well into late Renaissance times. In the matter of competitions, however, the first industrial exposition took its cue not from physical combat but from the more prestigious salons of painting and sculpture. An exposition is, after all, a show for honor and prestige, not a village trade fair, and it seems natural that an exposition staged in Paris would turn to the salon for its model: special exhibit enclosures, juries scrutinizing objects on display, and the final awarding of medals and certificates.(6)

Triumphal processions were another of the devices for formal celebration that Neufchâteau and the exposition committee appropriated for their new event. In the past, such ceremonies were accorded to many groups who were invested with dignity or had acquired glory. A king taking formal possession of a town, the Rector of the University of Paris receiving his annual dues at the Second Lendit fair, an army returning home from a triumphal campaign — the sense of high moment and solemn significance attendant upon such occasions would help to dignify the final proceedings of the industrial exposition. Music, speeches, fireworks and spontaneous cheering were the sounds and sights of unity that the revolutionary leaders were anxious to bring to their festivals.(7)

A momentous occasion demands dignified space. For the task of preparing the exposition grounds at the Champ de Mars, Neufchâteau turned to François Chalgrin, the future architect of the Arc de Triomphe. Considering that the plans for the festival were conceived and executed in great haste, the result was impressive. One contemporary, Joachim Le Breton, described the classical effect of the exposition grounds:

In the middle of a vast circle of porticos, the products of our manufacturers, elevated on a Temple of Industry, formed a perfect square, composed of a double row of Doric columns, detached on all four sides and mounted on a stylobate. In the middle was placed the figure of Commerce. This temple was destined to receive the objects of Industry distinguished by the Jury." (8)

Auguste Géradin, "Visitors at the Temple of Industry"

On September 19, 1798, the Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française commenced with a formal procession. Neufchâteau had made all the arrangements, making sure that the public would be suitably impressed by the alliance of music, the arts, military power and academic prestige.

First came the trumpets, sounding a martial prelude for all who followed. Trumpet fanfares had been the main musical heralds of nobility. Let them now proclaim the festivals of the Republic!

Then came a detachment of cavalry. Spectators would undoubtedly glow with pride as they recalled the recent French victories in the Italian campaign, and turned their thoughts to young Bonaparte bringing glory to the Republic with his campaigns in Egypt and the Near East.

Next came two platoons of marchers bearing ceremonial maces. Once again, the formal standard-bearing ritual of royalty was taken over and put into service of the Republic.

Following them came rollicking tambourine players. As in so many previous festivals of the new government, there was a Bacchanalian, free-for-all element in the proceedings. By 1798, these carnival elements had been subdued and forced into line by the authorities. But the tambourine still represented the good times, freedom, and celebratory nature of the festivals of the Republic. The tambourine was the people's instrument of merrymaking. (9)

Close behind these festive makers of glad noises were the members of the military band. Following on the heels of the Dionysian tambourines, the martial music served to bring the listeners thoughts back to the serious business of the day: the glory and might of the new Republic.

Next came a platoon of infantry. These men were the mainstay of the French army — less splendid to look upon than the cavalry, but the solid iron which secured the victories at home and abroad for La France.

After the infantry passed by, the heralds marched, waving aloft the banners and insignia of the Republic. These new banners were the most obvious emblems of change in France. Gone were the gold and white fleurs-de-lys of the Bourbon dynasty. Now the tricolor soared over the Champ de Mars.

Next, in solitary splendor, came the man in charge of regulating and coordinating the festival itself — a man not named in the documents. Was it François Chalgrin? Jean Chaptal, chemist, a rising star destined to replace Neufchâteau as Minister of the Interior? We do not know.

Then followed the "artists enrolled for the exposition" — the 110 inventors and industrialists whose works were on display. The visual effect of these marching manufacturers must have been to give them a status comparable to that of the infantry and cavalry: "Here are the industrial soldiers of France, men who supply the arsenal of war against the enemies of the Republic!"

The tenth wave was made up of the distinguished members of the jury. This group included several members of the prestigious Institut de France, men of letters, artists (including Joseph-Marie Vien, himself a member of the Institute and former teacher of Jacques-Louis David), as well as members of the foremost agricultural and mining societies. If the previous contingent of industrialists seemed comparable to the army, this group recalled the majesty of the Republican government: the men who, enfranchised by the people, would deliberate and pass judgement upon the works of those who would serve France.

Then came members of the central bureau of the Directorate, powerful politicians who controlled the destiny of France at the time. These men are not named, but probably included Emmanuel-Joseph Sièyes, President of the Directory. It was Sièyes who would later vigorously support — unsuccessfully, as it turned out — the establishment of the industrial exposition as a permanent part of the annual Festival of the Foundation of the Republic.

Next came "the minister responsible," François de Neufchâteau, Minister of the Interior and father of the event. During his two ministries he had arranged many such public spectacles, such as the festival of Spouses and the festival of Youth. Thus far, he had survived all the waves of overthrow and execution of the past decade, and now presided over what was to become the most influential of all his creations. The ensuing ten national industrial expositions in Paris, and all subsequent international expositions, owe their origin to the revolutionary fervor and visionary planning of this one man.

A final platoon of infantry concluded the procession.

Neufchâteau and his entourage marched with dignity around the entire exposition grounds. Originally, it was planned that he would deliver his inaugural speech from the Temple of Industry. But since that noble structure was still incomplete on the inaugural day, the minister stood atop a knoll that elevated him above the crowd, and delivered his testimony:

Citizens:

These are no longer those unhappy times when enslaved industry scarcely dared to produce the fruit of its meditations and researches; when disastrous rules, privileged corporations, and financial restrictions nipped in the bud those precious seeds of genius; when the arts helped industry to become at the same time the instruments and the victims of despotism, and even aided in weighing down all citizens beneath the yoke of despotism, and could only succeed by flattery, corruption, and humiliations of a shameful servitude.

But now the torch of liberty belongs to industry. The republic rests upon unshakeable foundations. Now industry is borne aloft in swift flight. . ." (10)

Neufchâteau continued his remarks in a less lofty, but no less serious vein by commenting on the lamentable fact that the very term, arts mechaniques, had become debased by old prejudices against such manual work. He cited with approval Francis Bacon's dictum that his history of the mechanical arts was true "philosophie."

Thus early, in 1798, Neufchâteau is sounding a theme that will emerge again and again during the international expositions: the dignity of labor. Artisanship and the making of useful objects for daily use would be praised in this and every subsequent exposition throughout the nineteenth century. This elevation of industry to a high status would be further encouraged by Napoleon, especially during the industrial exposition of 1806. What Miriam Levin has called "moral technology — a mechanism for cultivating attitudes and behavior by appealing to personal sentiments and desires"(11) finds a powerful expression in official support for industrial technology.

Neufchâteau concluded his oration with an apology that the brief time between the announcement of the exposition and its opening prevented many important manufacturers from participating.(12) After the speech, the military band played rousing military airs as the crowd dispersed to view and contemplate the products of French industrial ingenuity. One hundred and ten exhibitors had responded to the Minister's call. Their products were placed on display in booths within the arcades encircling the Champ de Mars. What the crowds saw was a mixture of eccentric inventions by individuals and the products of highly organized industry. Citizen Chaussier offered his "keratome" as the latest and ultimate instrument for cataract operations. Citizen Lacaze showed his "machine for the purpose of retrieving wood from water without the necessity of workers entering the river." Citizen Guérin offered for sale his paintings, made from colored plumes, of birds from foreign lands.

The master horologer, Abraham-Louis Breguet, received a gold medal for his “metronome clock,” which employed a novel mechanism for keeping strict time and serving as a music metronome:

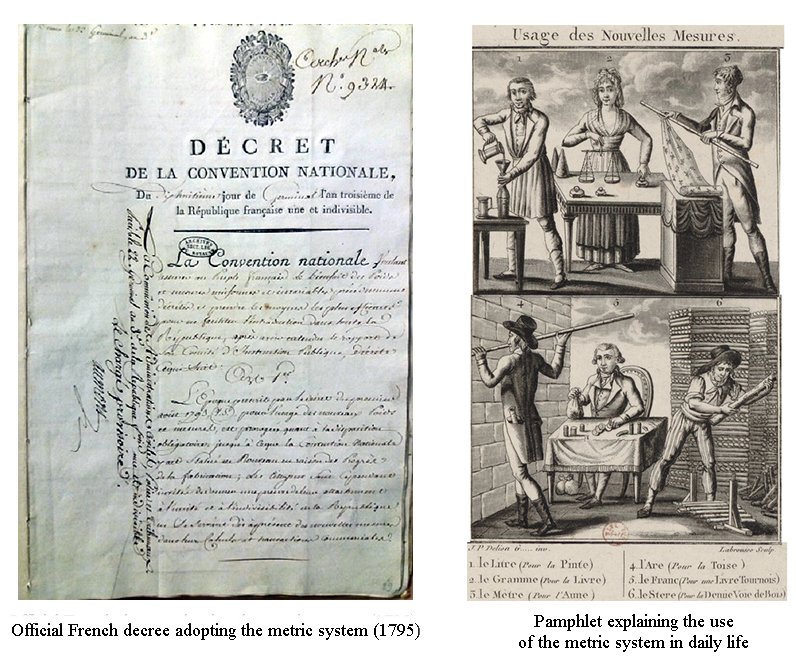

One especially public-spirited inventor, Citizen Kutsch, won an honorable mention with his mechanical device that demonstrated the "divisions of the republican system of measures." The metric system had been decreed by the Revolutionary government only three years before, and much of the populace was still bewildered by the new system of liters, grams, and kilometers. The 1798 exposition marks the first public attempt to educate people about this new system.

Later, in the 1867 exposition, French authorities, hoping to spread the gospel of logical measurement throughout the world, once again put forth a display of the metric system in the central court of the Palace of Industry. When the International Bureau of Weights and Measures was formed in Paris in 1875, the metric system was adopted as the world-wide standard for science. This legacy of the Revolution still stands as one of its most profoundly universal influences.

The Arsenal of the Republic

But the government had in mind to encourage something more substantial than bird pictures and log grapplers, more important even than a device that helped decipher the mysteries of the metric system. The Republic needed products that would help France survive in the face of foreign competition. The exposition jury, in its official catalog for the exposition, noted that "products which could be offered that were comparable to those of British industry" (13) would be especially welcomed. When the jury made its selection on the final day of the exposition, it chose products that seemed to offer the best chance of competing successfully with the English. Twelve prizes and eighteen honorable mentions were awarded. Four companies which did not enter were also singled out for praise by the committee, that stated its "regret that the citizens... were not able to contribute to the exposition." First-mentioned among the absent was "Citizen Boyer-Fonfrède, whose cotton fabrics rival the most beautiful such products of England." (14)

Among the winners were eight Parisians and four provincials. The products displayed by them ranged from steel manufacture to bonnets, typography to spun cotton, pencils to pottery. After the distribution of prizes, the winning exhibits were solemnly placed inside the now-complete Temple of Industry. In its final report, the jury declared that "we may announce to our government that the moment has come when France shall escape from servitude to the industry of her neighbors." (15)

This formal enshrinement of manufactured products gives us a clear insight into the purposes of Neufchâteau and the government. Instead of relics from the past, the public is invited to pay homage to the best products of the present. We must imagine ourselves as Jacques and Marie Bonhomme, workers from the Saint Antoine quarter, mounting the stairs with cap in hand to the circular temple in the center of the exposition arcade. There, laid reverently on a pedestal, lies a watch, a bolt of cotton, a pencil, a segment of steel, a decorated porcelain. The Bonhomme citizens see more than objects to be purchased and used: they behold symbols of the excellence inherent in the new Republic, proof of the genius resident in all French workers, and canons against the commercial enemies of the nation. These are the new icons of Progress.

The close of the exposition was marked by festivities and more speech-making on the fifth and final official day. The Dépôt des fêtes nationales was raided for props, and so the final festivities were graced with two blue and two red chariot triumphs bedecked with gold trappings. The porticoes encircling the Champ de Mars were illuminated, and the military band played a final concert before the assembled crowds.

The crowds were disappointingly small, and the ceremonies evidently lacked the verve and sheer magnificence of the earlier Revolutionary festivals. The rather thin nature of these festivities during the final day of the exposition has led historian Marie-Louise Biver to conclude that these were but "the last vestiges of the great national festivals. It seems as though such events were now passé."(16) Undaunted, Neufchâteau rose to the occasion by declaring the Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française a success. "Though our exposition has not been large," he declared, "we must recall that this is but our first campaign, and it has been a campaign disastrous to the interests of English industry. Our manufactures are arsenals most fatal to the power of the British."(17)

This pugnacious conclusion was long remembered on both sides of the Channel. In 1834, Stéphane Flachat wrote in the catalogue to the industrial exposition of that year:

More than 30 years after this prediction by the minister of the Directorate, we may ask: has it come true? Our manufacturers prosper, and move forward with an admirable spirit; but English progress is equally rapid. Each nation retains its own superiority: the one, in mechanical arts; the other, in chemistry and objects of taste. Far from seeing an increase of mutual animosity, every day sees a diminution of their mutual hatred in proportion to their industrial progress, and a growth of alliance between them. We must both widen the bases for commercial reciprocity. The unshakeable union of the two most industrialized people in the world will prove that industry forges peace, and not war.(18)

By 1834, the French were tired of wars, tired of revolutions, tired of the ceaseless conflicts that had consumed her people for almost half a century. Flachat is giving voice to the hope that will animate all future Parisian expositions: Progress means Peace, and Peace is a sign of the mutual understanding that necessarily rises out of Progress.

In 1844, the English writer for the Art Union visited the French national exhibition held in Paris that year. In his report to the readers of that journal, he gave a brief history of the industrial expositions in France, and pauses to reflect upon the remarks of Neufchâteau:

It deserves to be remarked that this first Exposition was viewed as a kind of military demonstration against the British empire.... These are memorable words, and they might suggest to us that our factories are the arsenals which furnish the most potent weapons for the maintenance and preservation of our national greatness. (19)

In the weeks following the exposition, it appeared that Neufchâteau would see his exposition become a part of the annual festivities of the Republic. He proposed that the industrial exposition should take place annually, and should be held in conjunction with a twin "Festival of Agriculture." But events in France were whirling toward other conclusions. On June 23, 1799, Neufchâteau was removed from his post by order of the Directory. Then on November 9, the Directory itself was overthrown by the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Republic was now a Consulate; both plot and cast of characters had changed. But the success and importance of the first exposition were not forgotten. As Guillaume Depping, writing almost a century after the event, concluded, this first exposition "was only an attempt (essai), but it was an attempt full of promises."(20) After a three year lapse, the new regime would revive Neufchâteau's dream of a festival to honor and promote the "industrial arts" of France. From 1801 to 1849, Paris would host no fewer than ten more national expositions, each larger and more ambitious than its predecessor. All throughout Europe, the French model was copied. There were more than 150 such national industrial expositions held in Europe between 1801 and 1851. It was the clear success of these national industrial expositions that inspired Great Britain to host the first international exhibition in 1851.

The outstanding irony of this development is that the exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française, born of an intense, revolutionary nationalism and aggressive anti-British fervor, would give rise to international expositions that promulgated the virtues of internationalism and peace. In 1798 there was no question of taking the higher moral ground, and seeing Great Britain as part of the grand march of civilization in which all great nations marched in honor. It would be another half century before the sponsors of the international expositions gilded national pride with the rhetoric of Progress for the human race.

1798 Exposition medal designed by Benjamin du Vivier

NOTES

1 Australian World Exposition Project Sponsors' Report and Feasibility Study (Melbourne, Australia, 1966)

2 For a reliable, but not exhaustive, compendium of descriptions of this fête, see Marie-Louise Biver, Fêtes révolutionnaires à Paris (Paris, 1979), pages 87ff. The best interpretation of the festival of the Supreme Being is still Mona Ozouf's, in her seminal Festivals and the French Revolution (translation of La Fête Revolutionnaire, 1789-1799), Cambridge, Mass., pages 106 ff.

There is a very lovely rendition of Gossec's " Hymne à l'Etre suprème" on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NM5oa51yio&feature=youtu.be

3 Costaz, Claude Anthelme, Histoire de l'administration en France, Vol. II (Paris, 1832), pages 315-316. Patricia Mainardi, in her excellent Art and Politics of the Second Empire, cites other, partially conflicting versions of the origins of the first exposition. See especially note 3 to Chapter 2, page 199.

4 Recueil des lettres circulaires, instructions, programmes, discours et autres actes publiques, émanés du citoyen François de Neufchâteau, pendant ses deux exercises du Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2 volumes, Paris, 1798-1800.

5 Helen Auger, The Book of Fairs (New York, 1939 and Detroit, 1971), page 134.

6 In this light, attempts to link the 1798 exposition with the "exposition" of French tapestries and pottery in 1797 seem to me misdirected. The 1797 event, instituted because of the closure of English and continental markets of French goods, was held more in the spirit of a garage sale than an exposition. There were no prizes, and objects were on display for sale, not for the encouragement of French industrial prowess.

7 For a good discussion of triumphal processions and spectacles in France and other countries, see Roy Strong, Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals, 1450-1650 (Suffolk, England, 1984), and Splendor at Court: Renaissance Spectacle and the Theater of Power (Boston, 1973).

8 Le Breton, Rapport sur les Beaux-Arts (Paris, 1806), pp. 179-180.

9 It is possible today to hear what these tambourine processionals might have sounded like. François Gossec, a prolific composer, member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux Arts and the Legion d'Honneur, composed a "Tambourin" for flute and tambourine, which has been performed and recorded often in our century.

10 Cited in Industrie Exposition de 1834 (Paris, 1834), page 17.

11 "The Wedding of Art and Science in Late Eighteenth-Century France," in Eighteenth-Century Life, Volume 7, 1981/82 (May, 1982), page 54.

12 Only 16 of the 88 departments of France were represented at the exposition

13 Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française. Catalogue des produits industrielles (Paris, An VII — 1799), page 18.

14 Cited in Industrie Exposition de 1834 (Paris, 1834), page 17.

15 Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française. Catalogue des produits industrielles (Paris, An VII — 1799), page 24.

16 Fêtes revolutionnaires à Paris, Paris, 1979, page 128.

17 Recueil des lettres circulaires, instructions, programmes, discours et autres actes publiques, émanés du citoyen François de Neufchâteau, pendant ses deux exercises du Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2 volumes, Paris, 1798-1800.

18 Stéphane Flachat, Industrie Exposition de 1834 (Paris, 1834), page 18.

19 Anonymous article in Art Union, (London) August, 1844, page 226.

20 Guillaume Depping, "La Première Exposition à Paris en 1798," in L'Exposition de Paris (1889) publiée avec la collaboration d'écrivans spéciaux (Paris: Charaire et Fils, 1889), page 19

STATISTICS

Opening Date: September 19

Closing Date: September 21

Site: Champ de Mars

Exhibitors:110

Top Official: François de Neufchâteau

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Costaz, Claude Anthelme, Histoire de l'administration en France, Vol. II (Paris, 1832)

Depping, Guillaume. "La Première Exposition à Paris en 1798," in L'Exposition de Paris (1889) publiée avec la collaboration d'écrivans spéciaux Paris: Charaire et Fils, 1889), pages 6 ff.

Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française. Catalogue des produits industrielles (Paris, An VII – 1799)

Mazade d’Avèze, M. Idée première de l’exposition de l’industrie française (Paris, 1845)

Recueil des lettres circulaires, instructions, programmes, discours et autres actes publiques, émanés du citoyen François de Neufchâteau, pendant ses deux exercises du Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2 volumes (Paris, 1798-1800)

Simian, Charles. François de Neufchâteau et les expositions (Paris, 1889)

Tomlinson, Charles. Cyclopedia of Useful Arts & Manufactures (London, 1852; reprinted with supplement, 1862)