The Russian and German Pavilions oppose each other at the 1937 Exposition (click the image for a lightbox view)

Click HERE for a 1937 video of the scene above

THE EXPOSITION INTERNATIONALE DES ARTS ET TECHNIQUES DANS LA VIE MODERNE, 1937

by

Arthur Chandler

Expanded and revised from World's Fair magazine, Volume VIII, Number 1,1988

In 1937, the Queen City of Expositions held court for the last time. World War One was scarcely two decades past. The most catastrophic war in the history of the human race loomed less than two years away. Paris, France, Europe, and all nations of the earth seemed poised in the eye of a hurricane, between the winds of World War I and World War II. The Exposition Internationale would be the final European enactment of the ritual of Peace and Progress before the deluge.

To their credit, the exposition officials recognized that they were celebrating in a deeply troubled world, and did their best to confront the actual and impending disasters within the framework of the exposition itself. The 1937 Exposition Internationale faced some of the most important dualisms that divided humanity against itself: the split between Paris and the provinces, between France and her colonies, between art and science, between socialism and capitalism, between fascism and democracy. The official philosophy of the exposition still paid homage to the twin gods Peace and Progress, as all parties at the great ceremony in Paris intoned the faith: no matter how bleak the world seems to be, the twin gods will see humanity through to a glorious future. "This great lesson in international cooperation will not be forgotten,"(1) predicted Fernand Chapsal, the French Minister of Commerce, in the official public report on the exposition.

By June of 1940, Paris would belong to the conquering Nazis.

DUALITY

On December 28, 1929, the French Chamber of Deputies passed a resolution calling for an "Exposition of Decorative Arts and Modern Industry," in 1936, to be placed under the direction of the Minister of Commerce. The exposition was first conceived as a follow-up to the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs Modernes of 1925. Though the attendance at the Art Deco fair was only a tenth of the number who visited the 1900 exposition universelle, France congratulated herself on having taken a decisive step in maintaining her leadership in cultural affairs. The 1925 exposition, though not as ambitious as the five previous Parisian world's fairs, was pronounced a succès d'estime for France. Even if France was losing her place in the first rank economic and political power, Paris could at least prevail in matters of taste. France planned the new exposition with an eye toward consolidating her claims to cultural authority.

Conceived during the victorious optimism of the 1920s, the Exposition Internationale of 1937 (the originally-planned opening was delayed for a year) was carried out in the anxious zeitgeist of the 1930s. In the spring of 1936, one of the most bitterly contested elections in the history of France gave the Communists and Socialists a dramatically increased representation in the legislature, thereby further polarizing an already deeply divided populace. The Great Depression, unemployment, and runaway currency inflation forced a change in the government's original plans for a decorative arts exposition. Given the precarious state of the national economy, the decorative arts did not seem a serious enough concern to justify the labor and expense of a major international exposition. Instead, the government announced in the Livre d'Or Officiel that it would integrate the exposition with "the overall plan of economic recovery and the struggle against unemployment."(2)

This explicit social and economic agenda marks a new stage in French thinking about her expositions. In all the previous events, increased business was recognized as an economic by-product of staging an exposition. But it was a by-product, and not part of the official plan. Idealist promotion of the belief in Peace and Progress, advancing national prestige, and contributing to a worldwide exchange of information – these were among the principal stated goals of the past universal expositions. The 1937 exposition marks the first time that an exposition is launched in order to shore up a sagging economy and to provide jobs for the unemployed.

Though the decorative arts would not be the major focus of the new exposition, the exposition planners believed that the arts themselves should take an active part in the "struggle against unemployment." Because of the Great Depression – and the trend among painters and sculptors towards "unpopular" abstract art – the number of buyers to support the arts had declined sharply. To alleviate the widespread and growing poverty among artists – a embarrassment to the city which prided itself as the home and center of fine art – the nation of France and the city of Paris commissioned 718 murals, and employed over 2,000 artists to decorate the pavilions. The exposition was, in this respect, a kind of equivalent to the WPA program in the United States, where the government funded hundreds of mural projects in an effort to sustain working artists.

Sonia Delaunay’s murals “Propeller,” “Airplane Emngine,” and “Instrument Panel” in the Aviaition Builing of the 1937 Exposition

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Detail of the Propeller Mural

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Since the decorative arts were not to be the major subject or theme of the great exposition, what would take their place? As time went on, the objectives themselves wavered and shifted in the political storms. Some legislators thought the exposition should celebrate "Workers’ and Peasants’ Lives," in an attempt to heal the split between Paris and the provinces and to give an egalitarian cast to the exposition’s theme and purpose. Others wanted to see the artisan exalted, in an attempt to ennoble colonial craftsmen and to fix the status of art as a decorative auxiliary to social concerns. It was finally decided that the world's fair would take as its theme the division that had grown up between the arts and technology. The very title – "International Exposition of Arts and Technics in Modern Life" – shows the decisive split from the spirit of the earlier expositions universelles. The fairs of the earlier era and the event of 1937 are all "expositions" – shows of the products of human ingenuity, under the aegis of Peace and Progress – but the "universal" is gone from the name and nature of the newest fair. All previous expositions had been international; but national rivalries were supposed to be subordinated to larger, "universal" concerns: the elevation of taste through the arts and the improvement of everyday life by science through industry. The title of the 1937 exposition breaks down the real meaning inherent in the earlier term "universal" into its component parts: the nationalism inherent in the competition for prestige, the fundamental duality between the arts and technics, and the transforming power of art and science.

The title of the 1937 exposition suggests another change in the thinking of the planners, a change as fundamental as the shift from "universal" to "international." Now "Art" and "Science" no longer exist as absolute values. Art becomes artisanship, science becomes technology. The value of art and science derives from its social utility, the exposition planners announce at Paris 1937. Application to daily life is the highest measure of worth. This utilitarian tendency, always present in the philosophy of the Parisian expositions, is now carried to its logical extreme. Science is valued, not as an independent exploration of the unknown, but as a vehicle for social amelioration. Art is not the vessel of immortal truth, whose purpose is to "instruct by pleasing": it is a decorator of the useful. Both the right and the left wings of political life in the 1930s conspired to confine art and science to these subservient roles. The philosophy was as congenial to fascist Italy as to democratic France or communist Russia.

AN UNDISCOVERABLE SCHEME

By 1935, the new exposition had a theme and a name. But as 1936 drew closer, no detailed plans for the event had yet been drawn up. The opening date was moved up to 1937, and a commission set to work in earnest on the grand schemes and finer details. However, the compressed time frame hurried the commission into hasty decisions and improvisational planning. Jacques Gréber, supervising architect of the Exposition Internationale, expressed his dismay at the lack of foresight in choosing the exposition site and permanent structures:

If the exposition had been decided upon five or six years before the opening, I certainly would have recommended a site that extended beyond the confines of the city – more precisely, a site to house a great Park of the Future, with several permanent public buildings useful to the development of greater Paris.(3)

When the American correspondent for the Architectural Record surveyed the exposition, he could compliment the "cheerful magnificence of conception, peculiarly French," while at the same time lamenting that the overall objectives of the exposition were "foiled by a lack of coordination between the idea and the realization."(4) Jean Loisy, writing in L’insurgé, sneered that "the exposition has neither a leader nor a plan nor a program."(5 ) Looking back to the exposition of 1937 half a century later, François Robichon concludes that "the scheme of the whole was undiscoverable, since the placement of the 200 pavilions was made without any overarching plan, with the exception of those in the Trocadero Esplanade."(6)

As always with Parisian expositions, the work proceeded slowly, and the exposition opening time was pushed back again and again. It was an embarrassment for the French government to watch visiting nations complete their pavilions while bureaucratic delays and strikes drove the French commissioners to despair. At one point Edmond Labbé, chief commissioner of the exposition, resigned his post with a despairing outburst:

I am a dishonored man, and I herewith tender my resignation. The French pavilion will not be ready in time for the inauguration. The workers pay no attention to me. In spite of all my appeals to their honor and power, they still go on strike.(7)

Medal honoring Edmond Labbé for his work as chief commissioner for the exposition

Workers are not always swayed by the fine words Peace and Progress. Parisian laborers in 1937 demanded a pledge from the government that if they helped build the exposition, they would be guaranteed employment thereafter. Labbé was persuaded to continue, and the work proceeded. But would the fair ever open its gates to the public? Just a few weeks before the actual opening date, one of the commissioners approached the director of works and asked him:

"Since you're the builder of all this," the official asked,"can you tell me when the fair will be ready to open?"

"Well," replied the director,"I can't tell you exactly. But I do know that, according to the contract, I have to start demolition on November 2." (8)

The tardiness of the French workers was a major embarrassment to the French, since, by the time of the opening ceremonies, the Russian, German, Belgian, Danish and Italian pavilions were complete and ready to receive visitors. One newspaper ran the headline: "The exposition is late – as usual."(9) Right-wing journalist blamed the left wing for creating a "climate of disaster," while the left pointed the accusing finger at the capitalists for failing in their commitments and suppressing the workers.(10) The rancor of the recent elections continued to be played out in the newspapers and journals as the exposition proceeded.

"TOTAL DISORDER"

The major architectural event of 1937– the official "spike" of the whole exposition– was to be a splendid new modern art museum. There was little public outcry over the proposed demolition of the relic from the 1878 exposition. Writers for the Parisian journals of 1937 regaled themselves with epithets for the unloved Trocadero:

"a fat, misshapen, potbelly" –

"a monstrous snail" –

"a miserable amalgamation of crab, antelope, and turtle" –

"a vacuous idiot with a pair of asses ears!" (11)

The major legacy from the 1878 exposition universelle was leveled in 1934 without ceremony. "The old Trocadero will be mourned," remarked one French architect, "but only by those who habitually mourn the dead."(12) It was the third time that Paris had demolished a major structure from a previous exposition – the first to go was the old Palais of Industry, built in 1855 and torn down for the 1900 exposition – and in both cases, the destruction took place without protest from the public or critics. And in 1906, Dutert’s Gallery of Machines (from the 1889 exposition) was destroyed to enhance the view towards Les Invalides.

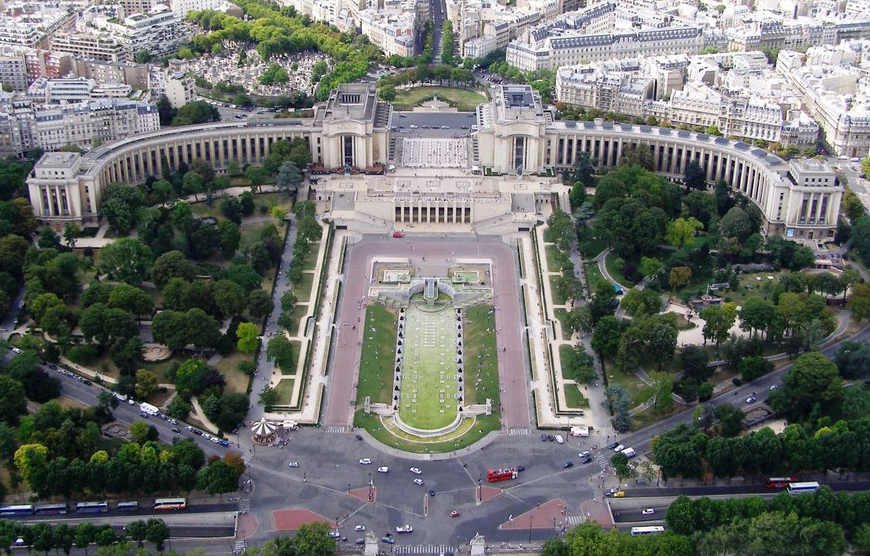

The new Chaillot Palace was to be the triumphant vindication of the present age over the past. The misshapen conglomeration from the 19th century would be replaced by a triumph of art deco modernity, a perfect unity of artisanship and technology. Unfortunately, as Robichon notes, "The reconstruction of the Trocadero palace took place in total disorder. After having first decided to demolish the old structure, they opted instead for camouflage."(13) Jacques Carlu, Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, and Léon Azéma were awarded the commission to rebuild the new Chaillot Palace along the same lines as the colonnade of the old Trocadero. The idiom of the new building would be modern, but not too much. As deputy commissioner Julien Durand assured the legislature during the budgetary hearings : "The old Trocadero will be replaced by a monument whose lines, in spite of their modernism, will fit well within the monumental tradition of Mansart, Gabriel, Ledoux, Percier, Fontaine, etc."(14) Both Carlu and Azéma had been winners of the traditionally prestigious Prix de Rome in architecture, and could be counted on the design a building not too far out of the mainstream. The radical modernism of Le Corbusier was passed over in favor of a style which mixed traditionalism and the international style.

This return to the past by way of neoclassicism has been seen by some observers as a prime symbol of fascism in architecture. Indeed, Albert Speer, chief architect of the Third Reich, thought so, and his German pavilion at the 1937 exposition was carried out in a spirit quite close to that of the Chaillot Palace. The wide, impersonal sweep of the colonnade conjures up for many a feeling of totalitarianism in modern guise: an updated imperial style that owes its vocabulary to the twentieth century but its imperial ambitions to Rome. It is a style conducive to a mood of subjection of the individual to the state – in short, an architecture of fascism.(15)

But in other respects, the Chaillot Palace continues a tradition begun in 1900 with the construction of the Grand Palais. In spite of the obvious differences in style, there are some striking parallels between the two buildings. Both were built on sites of buildings left over from previous expositions: the Grand Palais replaced the old Palais de l'Industrie of 1855, and the Palais de Chaillot replaced the Palais du Trocadéro of 1878. The Palace of Industry was the major legacy of the first exposition of Napoleon III's Second Empire. The Trocadero was the major legacy from the first exposition launched by the Third Republic. Both buildings recalled some of the basic design features of their predecessors: the Grand Palais, like the old Palais de l'Industrie, crowning its elaborately decorated stone sheath with a vault of glass and iron; the Palais de Chaillot retaining from the old Palais du Trocadéro the encircling sweep of the colonnade and the ceremonial fountains facing the Seine. Both the Grand Palais and the Chaillot Palace were conceived as permanent art museums – legacies of their respective eras to the city of Paris for the glory of France.

Aerial photo of the Chaillot Palace today (photo: Panoramio)

As it turned out, the new Chaillot Palace was not the most the exciting architectural event at the exposition. Le Corbusier, whose Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau had created such an uproar at the 1925 Art Deco fair, was excluded from all the design teams of the 1937 exposition. One of his students, Junzo Sakakura, designed the Japanese pavilion. But Le Corbusier himself was too uncompromisingly visionary for the exposition planning commissioners. Undaunted, and following the tradition of "refusée" painters from earlier expositions,(16) Le Corbusier and his followers erected a huge tent outside the exposition grounds, just beyond the Porte Maillot. Inside, they set forth his models and plans for the ideal city of the future. Said the writer for the Architectural Record: "It was one of the most exciting, convincing, and most easily remembered exhibits of 1937 Paris."(17)

Mural in Le Corbusier's Pavilion de l'Esprit Nouveau

THE TWO CULTURES

At the earlier French national fairs held in the first decades of the 19th century, many artists refused to lower themselves by appearing in the same expositions as the "lower" mechanical arts. Painters and sculptors displayed their work at their own annual and biennial salons, where patrons and purchasers entered the "higher" world of aesthetic beauty, far from clanking machinery. Since the 1855 exposition, though, artists agreed to compete with each other side by side with the industrialists. But for painters and sculptors, gold medals awarded at world's fairs never had the status comparable to awards from the annual salons. Artists felt that the fine arts were more noble and refined products of the human spirit.

At previous Parisian expositions, "Art" and "Technique" were always housed in separate pavilions or separate sections on the fairgrounds. This arrangement symbolized for all concerned the tacit truce between the historically-ennobled humanities and the upstart empirical sciences. Art ruled the realm of Beauty, while industry held sway in the domain of the practical. Art could profit by advances in industry – the use of photography in portrait painting was the most often-cited example – and industry borrowed liberally from the arts to lend grace to utility.

Though art and industry had coexisted at world's fairs, there were never any systematic attempt to integrate the two. Applied ornament might dress up the perceived graceless functionality of the machine; and machinery might serve as a subordinate subject for art (the first painting with a motorcar appeared in the frescoes at the 1900 exposition). In addition, artists were called upon to adorn official buildings with bas reliefs and free-standing works that symbolized the goals of the exposition. Within the expositions themselves, however, art and industry remained separate – separate in the nature and application of their basic values, and separate in the very exhibit space they occupied within the exposition buildings themselves.

The 1937 Exposition Internationale was designed in part to effect a unification between these forms of endeavor. In this case, though, the unification meant a subordinate position for art. There was fine art to be seen at the exposition, of course – in the retrospective gallery. And Picasso's Guernica, on display in the Spanish pavilion, showed that painters were still capable of making powerful statements about the moral dimension of the contemporary world. But the overall presence of art at the 1937 exposition was as decoration. The term artisan is used again and again in the official literature; and the word is used with the kind of respect that indicates the writers felt at artisanship was every bit as worthy as artistry. In the modern view, easel painting was elitist. The muralists and sculptors who adorned the walls of the industrial galleries were the artists truly in phase with the official philosophy of the fair.

Government support for the murals at the exposition was, as we have seen, part of the official effort to combat unemployment. Artists gratefully accepted this public support; and some of the most renowned French artists of the period – painters Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Albert Gleizes, sculptors Henri Bouchard and Alfred Janniot– staved off starvation with government commissions. But there was a subtle price attached to this patronage: modern painting and sculpture at the Exposition Internationale were reduced to the status of architectural embellishment. First the superiors, then the equals of industrialists, artist had now fallen to the level of plaster molding manufacturers and furniture decorators.

Railway and Airline

One of the most successful manifestations of the goals of the exposition was the Railway Pavilion. Four distinguished French architects – Alfred Audoul, Eric Bagge, Jack Gérodias and René Hartwig – designed a structure in the art deco mode. By day, the building's ribbed pylons stood forth boldly from the front of the building, emphasizing the geometric nature of the design. At night, lights shined through the opaque plastic, giving a striking sense of airiness to the whole.

The Railway Pavilion, with facade painted by Robert Delauny

Between the pylons, and all across the front of the building was a semi-abstract mural showing a rail car passing though a forest of loops and tracks.The official book of the exposition, Le Livre d'Or, significantly makes no mention of the names of the artists who painted the murals. After all, why mention them, unless one also mentioned the designers of cowcatchers or pull-down compartment beds?

The pavilion's interior carried out similar motifs: strict stylistic geometry, relieved by colorful, semi-abstract murals depicting the structure and power of rail transport. A cutaway model of the Hudson locomotive showed, by the use of flashing electric lights, how power is generated and transmitted within the engine. The graceful lines of light seemed a perfect realization of the belief that industry, too, had its own intrinsic beauty. The purpose of the exhibit was educational; but visitors must have been struck with the fluid beauty of the patterns of light as they flowed back and forth across the exposed sections of the locomotive engine.

Close by, these bas-reliefs by Pierre Le Faguay summed up the sources and international extent of influence of powered flight:

(Click the image for a lightbox view)

"The ‘spike’ of our pavilion, without a doubt, is the animated model showing the passage by ferryboat from Paris to London,"(18} the exhibit commissioners announced proudly. This enormous and intricately detailed model showed the departure from the Gare du Nord in Paris (with much of the city, including Montmartre, rendered with almost photographic accuracy), the debarking from Dunkirk, the arrival at Dover, and the destination at Victoria Station in London. The model was more than a miniaturist's dream, however. It represented the fulfillment of a vision begun in 1855, when Queen Victoria visited the first French exposition universelle. The model showed Paris and London as sister cities, bound together by efficient and convenient means of transportation. The ancient, bitter rivalry between the two nations, healed in 1855, damaged in 1889 (when England refused to participate in an exposition that celebrated revolution) and again in 1898 (the year of the Fashoda crisis, when English troops humiliated the French on the banks of the Nile), was now declared extinct. The technology of transportation sealed the growing friendship between England and France. Now traveling from Paris to London would be an easy adventure, efficient and inexpensive, to be enjoyed and profited from by all.

Close by the Railway Pavilion was one of the most dynamic displays of the entire exposition: the Palais de l'Air. Some thirty-thousand visitors per day crowded into the immense series of galleries housed in a pavilion designed by Audoul, Hartwig, and Gérodias. The centerpiece of the Air Pavilion was a vast gallery reminiscent of an airplane hangar. Like massive abstract sculptures, radial airplane engines rested on pedestals at wide intervals throughout the main gallery. From the ceiling, gigantic aluminum rings, reminiscent of the rings of Saturn or the paths of electrons, encircled a Pontex 63 fighter plane in the display designed by "artist-decorators" Robert and Sonia Delauny.

The Palais de l'air

The 1930s was still an era of romance with the airplane; and the exhibit planners took advantage of the public's fascination by arranging the pavilion to show, in every conceivable context, the place of flight in human civilization. Bas reliefs showed airlines tying together Europe (with France leading the way), the Americans, Indochina and Africa. Dioramas of paintings and mural-sized photographs showed the history of aviation. A "Gallery of Technology" demonstrated the problems of wind flow and corrosion. Military aircraft, parachuting, sport flying, and even model-airplane building – every genre of hobby, commercial, or military application – were all represented at the booths of the Palais de l'Air.

Night view of the Palais de l'air (Click the image for a lightbox view)

COLONIES AND PROVINCES

Guide booklet for the colonial empire exhibits

The most telling sign that art had declined into servitude was the manner in which artisanship was exalted over art, and the condescending admiration bestowed upon the artisans of colonial cultures by their rulers. The exposition coloniale had presented handiwork and crafts by the subject peoples of the French empire in a picturesque encampment out by the Chateau de Vincennes, for scrutiny and appreciation by the citizens of the governing nation. Now the colonials were brought back and placed in isolated splendor on the Ile des Cygnes in the Seine. This was the familiar French 1001 Nights dreamland, the exotic Orient and darkest Africa made real by theme pavilions and dusky natives hawking wares in the quartier d'outre mer. Here primitive artisanship thrived. Beneath the imported totem poles, between the fronds of the newly-planted banana trees, palms and cacti, the colonial artisans weaved fabrics and sang their songs on the Parisian island of outre mer.

In spite of the genuine attempt to see colonial cultures as part of the greater French family, the mood of cultural and racial superiority persisted. As he surveyed the exhibit of tribal masks from Gabon and the Ivory Coast, the official chronicler of the colonial exhibit, Marc Chadourne, has a vision of the message crying out from these wares: "I am black, but I am beautiful."(19) Chadourne could not see that the "but" is a mountain over which the entire world would one day have to cross.

France had her colonies, Paris her provinces. What the Isle des Cygnes was to France, the Regional Center, located in a remote corner of the Esplanade des Invalides, was to Paris. Here the French borrowed from the Chicago Columbian Exposition, which devoted a portion of the fairgrounds to the states of the union. The idea was transferred to Paris, where the "Provinces" seemed to the French as the equivalent of states. But Chicago does not signify to America what Paris signifies to France. No one came away from the Columbian exposition with the notion that the other states were provinces of Chicago. At the Regional Center of the 1937 exposition, the fundamental distinctions of prestige and power between Paris and the rest of France were made manifest.

In the Regional Center, picturesquely-clad artisans from the provinces displayed their native crafts in pavilions designed as hybrids that wedded French regional traditional styles – the Norman, the Gothic, the Renaissance – with the cool lines of the international style. The visual aspect of these regional pavilions was an effect miniaturized grandeur: reductions of older styles meant for larger buildings. In a spirit of cooperation, even the Ile de France – the province that includes Paris – participated with a structure that resembled the top part of one tower in the City Hall of Paris.

Official writing about the Regional Center is not the slightest bit condescending. “Long live regional differences among the French!” the commissioners insist. By being most emphatically themselves, writes André Liautey, the provinces, "serve a national cause." And what is the nature of this contribution? "Tourism, the hotel industry, and spa therapy."(20) What a far cry from the heroic call for national unity in the first national expositions. No longer the backbone of French agriculture and the textile trade, the provinces are now quaint outposts of Paris, useful and picturesque in their diversions from city life.

The Provinces at the 1937 Exposition

THE DIALECTICS OF NATIONAL PAVILIONS

In the domain of ideas, the 1937 exposition attempted to reconcile, symbolically, art and industry. From the political vantage point, the fair was a vehicle of nationalistic propaganda. The word "propaganda" had not yet acquired connotations of deception, and one saw the word everywhere, in French and foreign pavilions alike. Propaganda continued the tradition of national displays at all previous world's fairs. Each country did its best to show the world the superiority of the political and economic system that had produced the marvels on view in its national pavilions.

As a newly-recognized member of the power elite, the United States wanted to demonstrate the forward-looking nature of the nation. Gone were the obeisances to the European tradition, such as were embodied in the American building on the Quai des Nations in 1900. The United States pavilion, a towering skyscraper designed by chief architect Paul Weiner, showcased the Roosevelt's New Deal.(21) The Departments of Treasury, Commerce, Interior and Labor made the case that America was successfully combating the Depression through an unprecedented series of public works funded by the federal government. At the center of all the displays featuring the New Deal stood a huge relief map of the Capitol, where all visitors could admire the city planners' wisdom and foresight when they envisioned the political centerpoint the United States.

The United States Pavilion

Other countries as well stressed the virtues of their home government, but added allurements to promote tourism. The French erected a special Pavillon du Tourisme, where the beauties of France could be admired without the distractions of industrial or artistic exhibits.

The Italian building showed how lovely Italy had become even lovelier under the benign reign of Il Duce. The Soviet Union mounted the most expensive display of all: a map of mother Russia made entirely of gold studded with rubies, topazes, and other precious stones – a luxurious and luxuriant illustration the country’s industrial growth in recent years.

But the most striking feature of the Russian pavilion was not the exhibits of gold and propaganda: it was the placement of the building face to face with the Nazi pavilion. Nothing in any previous universal exhibition had ever matched this dramatic architectural confrontation. In the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, the two opponents faced off with self-aggrandizing monuments to their nationalistic spirits. According to his own account, Albert Speer, Hitler's architect in chief and designer of the German building, accidentally stumbled into a room containing a sketch of the Russian Pavilion. This ostensibly innocent accident enabled Germany to dominate its rival on the Esplanade. Facing the heroically posed Russian workingman and peasant woman brandishing hammer and sickle, the German eagle, its talons clutching a wreath encircling a huge swastika, disdainfully turned its head and fanned out its wings. At the ground level, a massively naked Teutonic trio stare at the Russian monument with grim determination.(22)

German and Russian Pavilions Face off at the 1937 Exposition

German and Russian Sculptures Representing the Strengths of their Nations

THE LEGACY

When the gates to the exposition closed in November of 1937, they closed on the final Ritual of Peace and Progress in the queen city of expositions. A total of 16,704 prizes had been distributed to participants. Over six hundred congresses had been held on an unprecedented number of topics. Over thirty-one million people had attended the fair, and the final balance sheet showed a loss of 495,000,000 million francs. But the officials pointed out that, during the year of the exposition, over four million more people attended theatrical and musical performances than in 1936, producing an estimated profit of forty million francs; admissions to the Louvre and Versailles doubled; the Métro collected fifty-nine million more fares; train travel increased twenty per cent; and hotels registered one hundred twelve per cent more guests. Clearly, the monetary goals of the exposition, taken in the larger context of the French economy, had been met.

In spite of these encouraging statistics, most observers counted the exposition as something less than an unqualified success. Only thirty-four million visitors – half the attendance of the 1900 exposition – attended this elaborate ceremony of the unification of Arts and Technics. The mood of the 1937 exposition carried none of the buoyant optimism that prevailed in 1900. Some enthusiasts talked of continuing the exposition into the next year; but the plan failed to win popular support. (By contrast, two years later, San Francisco would succeed in holding its Treasure Island exposition open for an additional year).

Amidst the technological wonders and charming pavilions of artisanship, there lurked an unpleasant feeling of tension, suspicion, and hostility at the Exposition Internationale in 1937. No one could mistake the brute confrontation between the Russian and German buildings. And there were other tangible evidences of mistrust. Almost none of the major nations distributed information about the materials and processes used in their industrial exhibits. Knowledge was the hoarded property of the nation that discovered and applied it. Guards in every pavilion were posted to stop visitors from photographing the exhibits. Even apparently public displays were to be appreciated, not studied. One architect was making sketches of the night-time illumination patterns of the French buildings – only to have his drawings confiscated and destroyed by the exposition gendarmes.(23)

The ritual of Peace and Progress was over. The medals were distributed, and the conquering exhibitors of forty-four nations politely applauded each other during the closing ceremonies on November 2, 1937. Soon the participants departed to their fortified cities and prepared to arm human pride with the tools of technology for the forthcoming tournament of blood. In the City of Light, the lamps were extinguished. The ultimate confrontation was at hand.

NOTES

1 Fernand Chapsal, Ministre du Commerce, introduction to Livre d'Or Officiel de l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris, 1937), page 16

2 ibid., page 14

3 Jacques Gréber, "La Leçon de l'Exposition de 1937," in L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, page 3

4 Anonymous essay in Architectural Record, October, 1937, page 82

5 Jean Loisy, "Le premier mai devait s’ouvrir l’Exposition," in L’insurgé, May 5, 1937

6 François Robichon, "Vers une architecture d'exposition, 1925-1970," in Le livre des expositions universelles, 1851-1989 (Paris, 1983), page 237

7 Quoted in Philippe Bouin and Christian-Philippe Chanut, Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris: 1980), page 206

8 ibid., page 201

9 Le Département, May 5, 1937

10 See, for example, the charges and countercharges in Vie Ordinaire of April 29, 1937, and Le Journal de la Mame, May 15, 1937

11 Louis Gillet, quoted with approval by the anonymous author of "En avant la musique: en voilà pour l'Exposition!" in La Revue Musicale, June-July, 1937, page 99. The writer makes it clear that Gillet's remarks are typical of the general comments about the unloved Trocadero.

12 Quoted in the Architectural Record, October, 1937, page 81

13 Robichon, op. cit., page 237

14 Rapport Julien Durand, given to the Commission of Finances, meeting of February 13, 1936, n.p.

15 For a rejection, or at least a qualification, of the view that the Chaillot Palace represents a French urge towards fascism or totalitarianism, see Bertrand Lemoine's essay on the Chaillot Palace in Cinquantenaire de l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et des Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris: 1987), pages 86ff.

16 Gustave Courbet in 1855, Edouard Manet in 1867, The Military School (including Neuville and Détaille) in 1878, and Henri Matisse in 1889

17 Architectural Record, October, 1937, page 83

18 Livre d'Or, page 341

19 Op. cit., page 216

20 Op. Cit., page 192

21 David Littlejohn's recent assessment of the United States pavilion seems unnecessarily harsh :"The effect, seen fro the Seine, was that of a gigantic moviehouse on Sunset Boulevard, or of a hotel on the Las Vegas strip. . . the interior was more funereal than festive." – from Littlejohn's essay on the American pavilion in Cinquantenaire de l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris, 1987), page 156

22 It is significant that, by the opening day ceremonies held on May 24, only the Russian and German pavilions were completely finished.

Additional note: some observers contend that, at the 1958 exposition in Brussels, Belgian officials purposefully placed the United States and Russian pavilions together to highlight their mutual enmity. At least one other writer (Jonathan Coe) suggested that the placement was rather an example of the Belgian sense of humor.

23 Architectural Record, October, 1937, page 8

Statistical Appendix

Opening Date: May 24, 1937

Closing Date: November 2, 1937

Size of site: 259 acres

Official Attendance: 31,411,593

Exhibitors: 44 nations

Expenses: 789,700,000 francs (including supplements to original budget)

Receipts: 294,000,000

Loss to Government: 495,000,000 francs (Figures vary according to different reports)

Top Officials:

Edmond Labbé, Commissaire Général

Paul Léon, Commissaire Général adjoint

Pierre Mortier, Directeur de la Propagande

Jacques Gréber, Architecte en Chef de l'Exposition

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barret, Maurice. "Leçon et avertissement pour l'Exposition 1937," Arts et métiers graphiques, 1936, numéro 51.

Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques, Paris, 1937 – Rapport Général, 10 Volumes (Paris, 1938-40)

Gillet, L. "Coup d'oeil sur l'exposition," Revue des deux mondes, May 15, 1937.

Hamlin, T.F. "Paris 1937: A Critique," American Architect, November, 1937.

Hitchcock, H.R., Jr. "Paris 1937: Foreign Pavilions," Architectural Forum, September, 1937.

Lacoste, R. ""Paris Exhibition of 1937," Great Britain and the East, July 15, 1937.

Lemoine, Bertrand, general editor. Cinquantenaire de l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et des Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris: 1987)

Livre d'Or Officiel de l'Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris, 1937)

Martzloff, R., and Cadilhac, P.E. "L'exposition de Paris 1937," L'Illustration, June 5, 1937.

Mock, Elizabeth. "Paris Exposition," Magazine of Art, May, 1937.

Moholy-Nagy, L. "Paris Exposition," Architectural Record, October, 1937.

"The Paris Exposition: Some of the Lighting Effects," Electrician, June 25, 1937.

"Paris 1937 Exposition" – special edition of Le Monde Illustré, May 29, 1937.

"U.S. Pavilion Carries Skyscraper Motif to Paris," Architectural Record, December, 1937.

Warnod, André. Exposition '37: la vie flamboyante des expositions (Paris, 1937).

A good internet reference source for the pavilions at the 1937 exposition:

http://www.worldfairs.info/expopavillonslist.php?expo_id=12#115