THE PARIS EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE OF 1900

by

Arthur Chandler

Expanded and revised from World's Fair magazine, Volume VII, Number 3, 1987

THE BATTLE FOR THE EXPOSITION

For three years following the exposition of 1889, France gloried in her triumph. She had shown the world that Paris was the queen city of expositions; that French engineering genius was second to none; and that, even without the official participation of other nations, the allurements and advantages of a world's fair in Paris were so great that few established or aspiring manufacturers could afford to stay away.

Then, in June of 1892, the Germans announced that they were planning an international exposition in 1896. This news was bad enough; but when Le Figaro reported later that month that the Germans were thinking of holding their event in 1900, there was consternation among French politicians, industrialists, and intellectuals. They realized that the country which hosted the exposition at the threshold of the new century would be the interpreter of the entire nineteenth century to the world. "The exposition of 1900," the organizers of the fifth Parisian exposition universelle later wrote, "will define the philosophy and express the synthesis of the 19th century." [1] If the Germans were to make the definitions, the luster of France would darken. Their military and industrial successes would be made to eclipse the triumphs of French culture. Berlin would become to Paris what Rome had been to Athens.

Moving with the speed engendered by unity of purpose, the French government declared, on the eve of Bastille Day, 1892, that France would host its fifth international from April 15 to October 15 in the year 1900. The announcements were unconditional: there was no sense of challenge or apology to the Germany. La France would hold her world court in Paris at the dawn of the twentieth century. The Teutons could come if they wished.

German reaction to the French announcement (and invitation) was mixed. What rudeness, what arrogance, for the French to snatch the proposed exposition from their neighbors! But in the 1890s, Germany knew when not to fight a doomed battle. Most newspapers confessed that the lights of culture and pleasure burned brighter in Paris than in Berlin. The German government and press decided that their artists and industrialists would be better advised to make a splendid show in Chicago in 1893 and Paris in 1900 than to attempt to wrest the exposition away from the French. France had finally won a decisive victory over her nemesis.

The Germans were driven back; but now civil dissent arose in France. Why must the exposition always take place in Paris? Several French cities were unhappy that they had been passed over as sites for the 1889 exposition. Following the decree of 1892, though, their objections took a different turn: "The universal expositions are ruining the provinces!" came the cry. In 1895, the municipal council of Nancy passed a resolution opposing the proposed exposition in Paris. J. Léon Goulette, editor of Nancien journal L'Est républicain, published a strident pamphlet, Pas d'Exposition en 1900!, in which he forcibly stated the feelings shared by many opponents of the Parisian fair. His most critical points were that the provinces lost revenues during the fair years, and that the exposition (and Paris) contributed to dissipation and depravity.

In March of 1896, the great confrontation between the opposing forces took place in the Chamber of Deputies. The opposition members crafted their rhetoric by committing to memory whole passages of Pas d'Exposition en 1900! But Alfred Picard, head of the exposition committee, was even better prepared. One newspaper gave this account of Picard's nimble performance:

The provinces are rebelling against Paris. You know how the argument goes: "This national activity is rushing to the nation's head while its limbs are withering. As the capital enriches itself, the departments are being depopulated and ruined."… "Stop the shouting," Monsieur Picard replies, "You will have most of the money that will be spent in Paris. Who, pray tell, will supply the poultry, the beef, the wine, the milk, the fruit and the cheese consumed at the fair? The gold of visitors from every part of the globe will fill the stocking of Jacques Bonhomme."[2]

Driven back on this point, the attackers redouble their fury and try to open another breach. "What about foreign competition?" Monsieur Picard, unperturbed, summons statistics to his aid: "In 1888 French exports were 3.2 billion francs; in 1890 they surpassed 3.7 billion; in 1891, 3.5 billion." All provincial opposition can do now is to bluster against the immorality of universal expositions. This is the only subject that Monsieur Picard refuses to discuss. He merely smiles.

Alfred Picard, Commissaire général

When the final count was taken, 419 members of the Chamber of Deputies voted in favor of the exposition, with 67 opposed. Soon after, the Senate approved the action by a voice vote. The provinces would once again have to resign themselves to serving as victualers to a Parisian exposition.

STORM CLOUDS

The time between the expositions of 1889 and 1900 was an era of economic prosperity punctuated by a series of political crises. The Panama Canal venture, undertaken with such confidence, came to a ruinous end. Not even Eiffel's designs could save the French engineering corps from the ravages of malaria; and when the French withdrew, thousands of shareholders lost their investments. Then in 1898, France's military suffered a humiliating reverse in the Fashoda Crisis, when the British army forced the French to retreat ignominiously from their position on the banks of the Nile. And in 1899, the Dreyfus Affair precipitated the worst political convulsions in France since the Année Terrible of 1870-71.

The effects of the Dreyfus case touched every phase of French social and political life. Until the young Jewish officer was finally pardoned by the government that had stripped him of his commission and banished him to a penal colony, the fate of the exposition was is jeopardy. Virtually every nation of the world condemned the French nation for what seemed like a blatantly anti-Semitic act. Even the United States, one of France's closest allies during these years, threatened to boycott the exposition if Captain Dreyfus remained in prison. When President Loubet finally issued the pardon in September of 1899, France and all the world breathed a collective sigh of relief. If the threatened boycotts had taken place so close to the opening date, the exposition would have been an embarrassing disaster. [3]

Once the Dreyfus fair had been resolved, the exposition universelle could play the same role it had in 1855 and 1878. The French could show the world once more that they had the courage and ability to overcome adversity. For the citizens of other countries, the fair would demonstrate again that the spirit of France could bring harmony from dissension, peace from strife. For the people of France, the exposition would bring together a population which, only a few months before, had been bitterly divided.

PREPARATIONS

In the years between the official approval of the fair and the opening day, Picard and his fellow commissioners set to work unceasingly to prepare the international exposition worthy to crown the century. All the major powers and many smaller nations — 47 in all — accepted invitations to participate. What nation would wish — or dare — to be absent from climax of the nineteenth century and the inauguration of the twentieth? Even Germany was welcomed — the first time that the new German nation had ever participated in a French exposition. After the defeat of the French at the hands of the rising German Empire in 1871, La France did not deign to invite the new nation to the expositions of 1878 or 1889. But time, and the courteous idolatry of French culture by cultured Germans, soothed old wounds. Kaiser Wilhelm, gallant as a young officer, filled the German pavilions with tributes to French culture, and graced the German exhibits catalog with this tribute:

Can one contribute more nobly to the great peaceful festival of the universal exposition than by recalling, by this return to the past, the memory of what the German people owes, in the domain of art, to its neighbor, and the memory of the homage rendered by Frederick the Great, one of the greatest minds of all time, to French civilization and art? [4]

Architects were given complete freedom to design in any style, and on almost any area of the expanded fairgrounds. Only the Trocadero Palace and the Eiffel Tower could not be torn down. Otherwise, successful entrants in the design competition could do what they wished. Participating nations could construct their national pavilions in any style, and display whatever they wished therein. The sole limit was the space assigned to each.

But almost immediately, the limitations of space became an issue. The Japanese delegation complained — to no avail — that the area given their nation was much too inadequate for their needs. When the Americans learned that the United States would not be allowed to place their pavilion on the Quai des Nations with the other first-rank powers, they launched an official protest — also to no immediate avail. The American Commission then began to apply strong direct and indirect pressure to the French government. Had the gracious hosts forgotten that "American trade returns exceed ten billions of francs — a total that is in excess of France and Germany together"[5] ? Ferdinand Peck, Commissioner-General of the United States, wished to "establish the fact that the United States have so developed as to entitle them not only to an exalted place among the nations of the earth, but to the foremost rank of all in advanced civilization."[6] The French, no doubt, politely demurred from this colossal presumption. But the United States pavilion was finally squeezed in between those of Austria and Turkey on the Quai des Nations, and every other country had to give up a small portion of their own space to make room for this upstart nation.

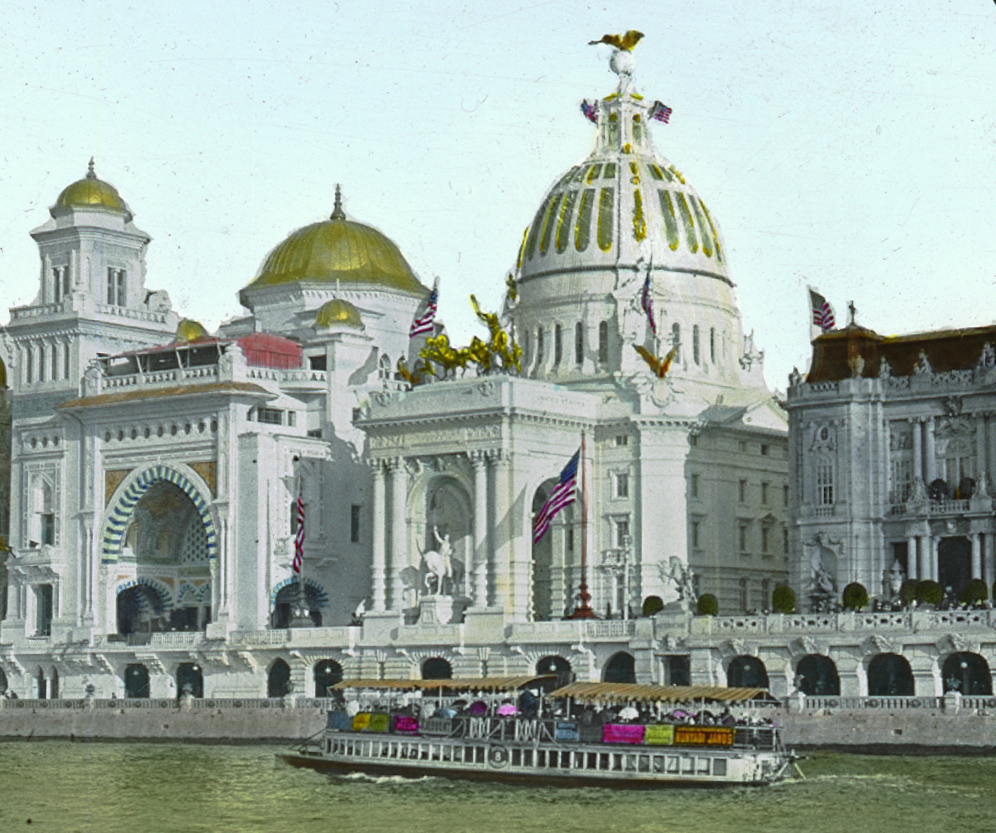

The American Pavilion (center) at the 1900 Exposition

When it was not preoccupied with coordinating the foreign exhibits, the French Commission was laying out plans for the fairgrounds. The traditional site, the Champ de Mars, would be used, as well as the Trocadero Hill, the Esplanade des Invalides, the area around the old Palais de l'Industrie, and the Seine riverfront land connecting these areas. The total area of the fairgrounds made the 1900 exposition universelle the most extensive in history — 543 acres in all.

And therefore, declared the Commission, should not this grandest of all expositions have its clou — a signature building that would equal or surpass the Eiffel Tower?

As soon as it became known that the Exposition Committee was thinking about a centerpiece for the 1900 fair, officials were deluged with bizarre proposals, most of which suggested transforming the Eiffel Tower itself. One schemer suggested turning the lower half of the Tower into a waterfall and crowning the upper part with a 450-foot tall statue of a woman, through whose cavernous eyes powerful searchlights would scan the fairgrounds. Clocks, sphinxes, terrestrial globes — all would–be transformers of the Eiffel Tower were obsessed by the urge to crown or decorate the structure with something.

Alphonse Mucha's plan to transform the Eiffel Tower, with monumental sculptures representing Progress

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

In the end, the Committee settled for applying a fresh coat of golden-yellow paint to the spike of the 1889 exposition, and turned its attention to more reasonable alternatives.

After much deliberation, however, the 1900 committee could come up with nothing to surpass the Eiffel Tower. Such an achievement, they discovered, is not easily matched. A number of less spectacular ideas were approved as "triumphs" for the exposition: the completion of the Pont Alexandre, perhaps the loveliest bridge in Paris; the construction of two permanent fine arts buildings, the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais; a ferris wheel; a Street of Nations along the banks of the Seine; the opening of the new Metropolitan underground railway and the mammoth Gare d'Orsay. But none of the ideas, however worthy in its own right, could match the Tower. The best argument was that the new vista from the Fine Arts Palaces on the Right Bank, across the Pont Alexandre, culminating at the stately dome of Les Invalides, was itself the finest spike of the exposition.

Grand Palais and Petit Palais, with Les Invalides in the distance

For connoisseurs of Paris, this splendid new view of Les Invalides has been the one of the most attractive legacies of the 1900 fair. But as a statement of the social, intellectual, and artistic values, the vista symbolizes the primacy of traditional values over the new world of technology promised by the Eiffel tower. Should the crowning glory of Louis XIV stand as the definitive architectural statement of the 1900 exposition?

Contemporaries were unconvinced. But not even the critics wanted to see another Eiffel Tower — unless it could produce income. Edouard Lockroy, who had played a key role in the 1889 exposition, pointed out that "the masses come to these fairs to see something new and amuse themselves, The fair has become a festival. If the festival is not attractive, too bad for its organizers. They have wasted their time and our money." [7] A new vista of Les Invalides across the Seine is all very fine, Monsieur Picard; but the exposition must attract paying crowds to be a true success.

Lockroy's sentiments accurately prophesied the pervading spirit of the 1900 exposition. Since 1867, the balance between education and amusement at international expositions had been shifting ever more in the favor of amusement. The great catchwords, Peace and Progress, still dominated the catalogues and official reports. But in actuality, international expositions were becoming world's fairs. Concessionaires saw these events as golden opportunities to make fortunes in a hurry. Exhibitors began to reckon profits above patriotism as the dominant motive for participating in their national pavilions. And the exposition planning committees themselves came to feel more and more that the primary standard for success was the bottom line of the ledger book when the expositions closed their gates. At this opening fanfare for the twentieth century, Profit replaced Progress as the dominant motivating spirit behind the universal exposition. This is not to say that the writers or exhibitors had lost faith in progress or had become cynical about the prospects of achieving "the greatest good for the greatest number." But the 1900 exposition evinces, at every point, the sense that profit and entertainment had better come foremost in the minds of all who participated. In some respects, it is a return to the late Medieval spirit of the annual fair, in which the saints are honored and the proprieties observed, but the profit motive naturally engages the mind more immediately than the underlying faith that gave rise to the event.

And so the exposition commission set out to amuse the millions.

A TRIP TO THE EXPOSITION OF THE CENTURY

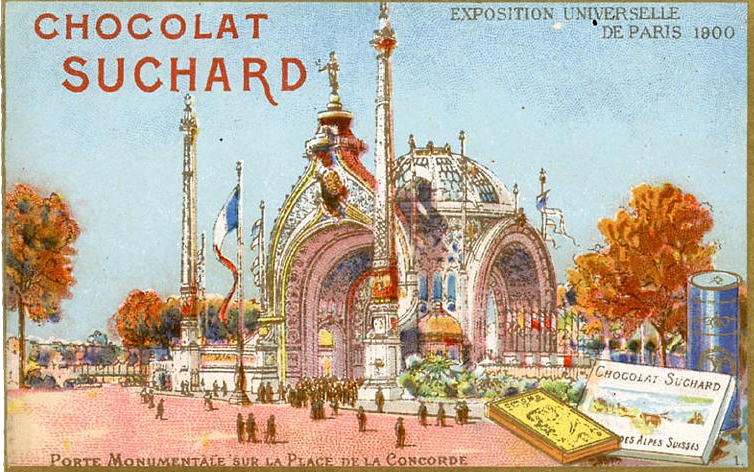

Imagine that you are one of the 60,000 visitors per hour that pass through the turnstile of the Porte Monumentale in the lovely Parisian summer of the years 1900 — the first summer of the twentieth century. You pause to admire the graceful sweep of Binet's monumental dome, a delicate bonnet of perforated iron work that rises gracefully over an area of 770 square feet, capable of sheltering 2,000 in the event of rain.

Advertising card featuring the Porte Monumental (click here to see Alphonse Mucha's design for he gateway)

You see the sculpture called La Parisienne atop Binet's entranceway, and laugh when you recall the drubbing local critics had given to this preposterous symbol of the host city.

Once passed beneath La Parisienne, you behold what many lovers of Paris, then and now, as the most elegantly powerful vista in the world: from the Petit and Grand Palais, across the Alexander Bridge, culminating at the Dome of Les Invalides — built by the Sun King but sacred as the repose of Napoleon's tomb. The exposition committee has pronounced this new complex of buildings and its accompanying vista the "spike of the exposition." And it is grand — if not quite so grand or appropriate as the spike of the 1889 exposition.

Now you proceed west along the banks of the Seine until you reach "Old Paris": the medieval village theme park erected by the city of Paris. Vieux Paris was the product of the active imagination of Albert Robida, a man who made his fame publishing cartoons of the future: a tomorrowland of airships, microbe-killing sanitary devices, and a strangely changed human race. Here, Robida had convinced the politicians at city hall that he should be allowed to bring to life Hugo's legend of religion and violence in medieval Paris. You stand amazed as musicians and jugglers stroll the streets, food vendors clad in period costume hawk meat pies and mead, knights battle with wooden swords, and an Esmeralda dances with her goat as Quasimodo looks down from his plaster Notre Dame. Victor Hugo's masterpiece is swept into existence by the Wizard of the Twentieth Century.

Entrance to Vieux Paris (click the image for a lightbox view)

From here you travel by moving sidewalk — choose fast lane, medium speed, and slow lane for desired velocity (you recall an amusing cartoon in one of the local journals depicting the riders on the three moving sidewalk tracks as symbols of Youth, Middle Age, and Decrepitude) — to the Trocadero Palace atop Chaillot Hill. What imp of the grotesque prompted them to erect this potbellied monstrosity twenty-two years ago! But as you amble through the encampment of the colonial exhibits put up by France, England, and Holland, you admit that the fountains of the old Trocadero are truly glorious.

The Moving Sidewalk, with an allegory of maturity (left), old age (center) and youth (right)

You turn with relief from the leering skulls at the Dahomey hut, cross over the Jena Bridge and gaze up the sweeping height of Gustave Eiffel's crowning achievement for the 1889 exhibition. Whatever they may say about the exposition of 1900, they have produced nothing to match the grandeur of the Tower. There is Monsieur Eiffel, leaning from the railing of the highest platform. You are sure that he has not recovered from the Panama Canal scandal. Nostalgic for the days of his triumph eleven years before, he looks down from his platform on the spike of the Exposition Tricolorée, over the crowds at the Exposition of the Twentieth Century.

Here, spread our before the tower as in fulfillment of its promise were the exhibits of the marvels of Progress. Tunisia and Algeria are here in their Arabesque pavilions, but you have tired of the allurements of colonial riches. You ride the railway cars with moving canvass dioramas that unrolled past you on their way across Russia. You try the American-style Ferris wheel — already purchased from the city of Paris by the city of Vienna — and pronounce it a whirling success. You ask the whereabouts of the sensational cinema pavilion, where Sarah Bernhardt's phonographed voice chants in synchrony with the crisp images projected by the newest 70mm motion picture camera. But alas — for fear of another tragic fire from exploded chemicals, the exposition committee ordered the pavilion closed after only as few showings in April.

Close by stands the Gallery of Machines, the Tower's companion from the 1889 exposition. As you enter Dutert's cavern of vaulted iron beams, you catch glimpse of Henry Adams, the brilliant grandson and great-grandson of American presidents, standing thoughtfully before the whirring dynamos.

Outside on the Champ de Mars, it is evening, and the colored lights from the Palace of Electricity burst over the cascades in the Chateau d'Eau.

Night Illuminations (Click the image for a lightbox view)

You pass before the Quai des Nations on you way back to the Alexander Bridge and Les Invalides. Here are Belgium and Germany in the year 1900 with flamboyant national building that evoke their medieval heritage. And here is the upstart American pavilion (placed on the Quai after the United States government kicked up such a fuss), paying homage to Les Invalides.

Weary of walking now, you pay for a ride on the Seine in a gaily bedecked bateau mouche, venerable survivor from the 1867 Exposition Universelle. Germanic spires and French-American domes and Swedish castles and Turkish turrets all shimmer in reflected the lights of the Seine, where pleasure gondolas and fishing boasts, bearing the Fluctuat Nec Mergitur motto of Paris, ply the evening waters.

You reflect on the dawn of the twentieth century in the dusk of the Paris evening. Peace reigns, Progress offers fresh fulfillments, nascent hopes. Never before have the twin gods received — or deserved — such celebration.

Quai des nations

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

THE TRIUMPH OF TRADITION

Even during the worst months of the Panama debacle, the Fashoda Crisis, and the Dreyfus Affair, the City of Paris prepared to receive the nations of the world. Juries were set up to select entries for the fine arts exhibits, assign concessionary rights to vendors, and pass judgement on the thousands of major and minor details necessary for launching the most ambitious world's fair in human history.

But when the exposition opened its gates on April 14, not all critics agreed that the most ambitious fair was the best. Melchior de Vogué, who had written a vigorous defense of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, was disappointed that architecture seemed to have taken a step backward:

In 1889, iron bravely offered itself to us naked and unencumbered, asking us to judge its architectural potential. Since that time, it seems as though iron has experienced the shame of the first man after its original sin, and feels the necessity of covering its nudity. Today, iron covers itself with plaster and staff. It hides itself in casings of mortar and cement. [9]

Both the Eiffel Tower and Dutert's Palace of Machines stood on the exposition grounds as silent testaments to the truth of Vogué's remarks. The buildings of the 1900 exposition fall into two distinct categories, each representing an essential element of the spirit of 1900: Traditionalist buildings that adhered to historically validated architectural values; and Art Nouveau structures that were trying to forge a new vocabulary of style appropriate to the twentieth century.

Art nouveau was making its splash in the fashionable world that year. One entire structure, the pavilion of the Hamburg art dealer Samuel Bing, was designed with the fragile elegance of the new style. René Lalique displayed with sumptuously decadent jewelry in the decorative arts display. The Union of Decorative Arts put together an ensemble of such elegance that their room at the 1900 exposition was preserved in its entirety, and may be seen today in the Musée Des Arts Decoratifs in Paris. Loie Fuller danced in her own art nouveau theater, whose whiplash curves matched the flowing movements of her dance.

Loie Fuller's "Serpentine Dance" at the 1900 Exposition

Most of the major exposition buildings — such as the Palace of Textiles, the Palace of Education and the Petit Palais — were Traditionalist: domed and pillared, heavily embroidered with Greek, Roman, Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo motifs, crowned with allegorical sculptures. Asian and African nations held fast to their indigenous architecture; European and American nations looked back to the Classical world, the Middle Ages, and the Baroque for inspiration in form and design detail. But, regardless of the source chosen, the total effect was one of retrospection. The past, not the future, was the guiding light.

It is easy to be critical of this obeisance to the past, and to charge it up to the stultifying forces of conservatism and arrière-garde thinking that afflicts bureaucrats when they are forced to make public statements. But, in one respect, traditionalist builders stood on surer ground than their art nouveau contemporaries who yearned for novelty in their bizarre pavilions. Costume, education, the fine arts — these were all human activities that had deep historical roots. To have housed a hundred years of French art from David to Bouguereau in a bleak steel warehouse museum would have constituted a fundamental error in taste.

But what about the pavilions that housed modern technological achievements? The 1900 exposition boasted a number of significant firsts: the first exposition display of x-ray machines, wireless telegraphy, automat food service, and sound-synchronized movies.

Wilhelm Röntgen’s X-Ray machine, developed in 1895, with an x-ray imafe of his wife’s hand

There was an immense area given over to automotive exhibits, and even a section devoted to "flying machines." What kind of exposition structures were built to house these untraditional activities? Here, the critics of "the merry-go-round style"10 of architecture were right on the mark. The Palace of Civil Engineering and Transportation, which housed some of the most innovative and influential industrial exhibits, was built in a flamboyant and eclectic style. Turrets, columns, cartouches, crowned with "pagoda–like roofs" — what did this hodge–podge of revived Greco-Roman motifs have to do with the nature of the exhibits inside?

Art Nouveau, however, offered no better solution to the problem. With its idiosyncratic stylizations of ivy vine and exquisite peacocks, the Nouveau style had nothing to offer but a precious cloaking for industrial design. Traditionalist builders were at least carrying on the aesthetic authority of thousands of years of religious and civic architecture. Art Nouveau, however lovely, proved to be a style for the rich. It fit neither the old "greatest good for the greatest number" social goals of the past, nor the emerging industrial aesthetic proclaimed by the Eiffel Tower. Hector Guimard’s entranceways for the new Métro were the only major public application of the Art Nouveau style to everyday life. Otherwise, the style proved to be a graceful dead end in the development of architectural taste.

The Art Nouveau Pavilion Blue at the foot of the Eiffel Tower; René Dulong, architect and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy, decorater

At the 1900 exposition, this authoritative garb of the industrial buildings shows a new kind of respect for the achievements of technology. In past expositions, the palaces of machines were invariably housed in buildings that represented, to Europeans at the time, a second–class or utilitarian kind of structure. As much as we might admire the ferro–vitreous masterpieces of the 19th century, to contemporaries these buildings were associated with railway stations, greenhouses, and closed-in food malls. The high style — buildings of stone, adorned with tasteful and authoritative embellishments inherited from the Classical world — was reserved for important functions and important people. To use this aristocratic vocabulary in housing industrial exhibits was to include them in this exalted rank — the rank of Art and Empire.

THE JEWEL AND THE GIANT

The most successful Traditionalist building was Charles Girault's (1851-1933) Petit Palais. The very name — "little palace" — conjures up the precise mood that the architect wants to evoke: elegance, tradition, condensed richness. Girault's jewel-like palace continues the mood of the Petit Trianon at Versailles and the Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne. All are exquisite miniatures built of light colored stone, highly regular in their overall floorplans, delicately exuberant. The central dome of the Petit Palais affirms the loftier glory of Les Invalides across the Seine. The Mansard roofs crowning the corners echoes the Louvre further east along the Champs Elysées. The interior courtyard recalls the inner ellipse of the 1867 Palais: a place where, in the midst of great art surrounded by a great city, one can pause among fountains and statuary to consider the Meaning Of It All. Or, as one observer put it, "There is a sense of restfulness in these quiet precincts that attracts the visitor unconsciously thither, and induces him to come again from day to day out of the wearying whirl of multitudinous sight-seeing." 11

Today, the Petit Palais houses the permanent art collection of the city of Paris. In 1900, the Petit Palais sponsored the retrospective exhibit of French decorative art. This was the only government–sponsored structure at the fair where the form of the building and the nature of the exhibit coincided exactly. Even those critics who were on principle opposed to lavish exterior ornamentation had to admit that the Petit Palais was a gem of its kind. The Revue des Arts Décoratifs, which championed the cause of art nouveau, grudgingly admitted that "here, at least, French grace has triumphed." "No visitor to the exposition neglects to visit this admirable palace," wrote Louis Rousselet, "And when one leaves it, he only regrets that within a few months its marvelous collection must be dispersed once again to the four corners of France."12

The Petit Palais; Charles Girault, architect

The Petit Palais was built as one of a pair of buildings dedicated to the arts and destined to grace the Right Bank after the close of the fair. But, whereas the Petit Palais charmed the critics, the Grand Palais reaped a whirlwind of criticism. The basic structure of the building seemed to derive from its destroyed predecessor, the Palais de l'Industrie of the 1855 exposition universelle. A massive stone sheathing, heavily embellished, statuary, and friezes, enclosed a huge interior of iron and glass. The spaciousness inside the building was indeed impressive. But, as an anonymous critic in the Revue des Arts Decoratifs put it, "What can one say about the Grand Palais, a sort of railway station where masses of stone have been piled up to support what? — a high, thin roof of glass. A bizarre contrast of materials! It is as if a giant were flexing his muscles, stiffening his arms and making a tremendous effort to raise a simple head-dress of lace above his head!" 13

Sculpture exposition in the Grand Palais, 1900

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Inside the Grand Palais, there were two distinct art exhibits running simultaneously: the Décennale, which admitted only works created during the past ten years; and the Centale, which reviewed the achievements of the entire 19th century. Strange to say, the 100 year retrospective was much more forward-looking than the exhibit of recent art. The artists of the Décennale were chosen by a jury controlled by the conservative Academie des Beaux-Arts. Traditional works predominated in the Décennale; but there were a number of striking Symbolist paintings that showed where academic realism was headed. "The Pursuit of Happiness" by Georges Rochegrosse, "The Descent into the Abyss" by Henri Martin were the favorites of the Décennale; and each showed that the realistic, narrative tradition of French painting was far from exhausted. Predecessors of Magritte and Dali, these artists have been all but forgotten in the eventual triumph of Impressionism and abstract art.

(Click image for a LIGHTBOX view)

The Centale exhibit was curated by the forward-looking connoisseur Roger Marx. Everyone expected to see the Olympians of French art on display -- David, Delacroix, Ingres, Meissonier. But many visitors were surprised to see Impressionist works on display as representatives of the glory of French art. Gauguin and Seurat each had one canvas in the show. Cézanne was represented by three works, Pissaro by 8, Manet by 12, Monet by an astonishing 14 paintings.

Not everyone was pleased by the admission of the "radicals" into the hallowed circle of officially-accepted art. A famous incident occurred when Jean-Leon Gérôme, the implacable opponent of the Impressionists, was accompanying President Loubet through the Grand Palais. When Loubet attempted to enter the Impressionist section of the Centale, Gérome held up his arms to bar the way. "You must not enter!" implored Gérome. "The shame of France lies in that room!"14

But, as has ever been the case with the Parisian expositions, the most daring artist held his exhibit outside the fairgrounds.

TRIUMPH OF THE REBEL

Auguste Rodin was no stranger to the Parisian universal expositions. He had hoped that his Call to Arms would win the applause of the critics and the public, and gain him admission to the 1878 fair. But Antonin Mercié's Gloria Victis won the palm, and Rodin was reduced to turning out ornamental decorations on the Trocadero fountain. In 1889, his Saint John the Baptist Preaching was exhibited, in spite of academicians' protests that Rodin had cheated by using life casts (taking a plaster mold from direct application to a model's body). By 1900, though, Rodin had emerged as the foremost sculptor in France, replacing even Carpeaux as the genius of the genre. Rodin had his own pavilion outside the exposition grounds — but this time, with the blessing and the financial assistance of the city of Paris. Long lines of admirers came to appreciate and pay tribute to the man who had successfully defied the skeptics and achieved renown. And though the exposition itself had opened with a performance of Saint–Saens' Hymn to Victor Hugo, in the minds of many visitors, it was Rodin who represented the apex of French genius in the last century. "He is by far the greatest poet in France," wrote Oscar Wilde to Robert Ross, "and has, as I was glad to tell myself, completely outshone Victor Hugo."15

Rodin and his assistants had worked frantically for years to prepare a plaster cast of his most ambitious work to date, La Porte D'Enfer — for the 1900 exposition. Originally commissioned for the Museum of Decorative Arts, The Gate of Hell had expanded into an immense autobiographical sketchpad. Over 180 figures seethed across its surface. A number of works presented in miniature here would emerge in full size throughout his career — Fugit Amor, Ugolino, and The Kiss (originally intended for the Gate, but removed by the sculptor as inappropriate), At the very top of the Gate brooded The Thinker, his massive naked form representing the essence and force of thought.

Plaster cast version of Rodin's "Gates of Hell"

No other figure at the pavilion so clearly showed Rodin's special ability to make his own rules in presenting an elemental human force. The coiled body needs no clothes, no symbolic books or quill pens, no grand gesture or pensive brow to express the force of thought. The unadorned male body is enough to express Thought.

A short distance from the Rodin pavilion on the Place de la Concorde stood another gate crowned by a quite different symbolic figure: René Binet's monumental entranceway to the exposition, surmounted by Paul Moreau–Vauthier's La Parisienne. Here, atop the perforated archway designed by René Binet, the figure of Paris welcomed the world to her exposition. She should have been the epitome of symbolic exposition art, the most apt sculpture of the entire event. She should have embodied the quintessence of Parisian character — taste, elegance, and artful beauty.

La Porte Monumentale and La Parisienne

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Moreau-Vauthier started by choosing the Sarah Bernhardt as the his model. No actress was so admired, so breathlessly adored by the public than "The Divine Sarah." By making her the archetype of the Parisian spirit, Moreau-Vauthier chose to show Paris mature, elegantly set forth in high couture, talented and above all — free. For her gown — a real divinity, he believed, must not be shown nude — Moreau-Vauthier turned to Paquin, the most celebrated couturier of Paris. The robes of La Parisienne have the look of high fashion: heavy but flowing, regal but allowing for freedom of motion. Atop her head is a crown in the shape of the symbolic ship of the city of Paris.

The most exquisite woman appareled by the best artist of the robe, set atop the entranceway to the greatest international exposition in the history of the human race. Surely a formula for success! But as soon as the stature was unveiled, the critics drubbed it mercilessly. With her aggressive, jutting and strutting posture, La Parisienne seemed all wrong, an assertion instead of a song. Every critic found something especially annoying about the lady of Paris:

"The statue is too large for the Porte Binet."

"You can't tell if she's standing or sitting!"

"Only the government has the right to allow artists to use the symbol of the city of Paris. It looks ridiculous atop that hussy's head!"

"It is the triumph of prostitution!!"

"The poor Parisienne was just plain ugly." 16

What exasperated the intellectuals was masculine assertiveness embodied in female form. Criticism was so vehement that there was even talk of removing the work before the exposition closed. But the plaster of Paris Parisienne endured until November, when she was crumbled to powder beneath the wrecker's hammer.

Why did The Thinker succeed where La Parisienne failed? The answer provides the key to the critical paradoxes of the entire exposition. Moreau–Vauthier had worked "following the formula," mixing in a little art-nouveau waves with a traditional, melodramatic pose and idealized modeling. Other sculptors at previous expositions had succeeded in portraying women as the spirit of France — Diebolt's massive stone portrayal of France that crowned the entranceway to the 1855 Palais de l'Industrie, the winged savior of Mercié's Gloria Victis group at the 1878 exposition, and Bartholdi's colossal portrayal of Liberty Illuminating the World. But by 1900, the old poses, even when treated with a dash of modernity, seemed hopelessly retrograde and didactic.

Rodin successfully symbolized abstract force with the human body. The thinker brooded over a world of everlasting suffering. Was it a world of squalor and injustice that Rodin showed to Oscar Wilde, Claude Monet, and tens of thousands of world citizens of the dawn of the twentieth century? "Even more beautiful than beauty itself is the ruin of something beautiful" Rodin had written. It is the glory of the human mind that thought — and thought alone — can, in the act of creative thought, give meaning to human life, a meaning that cannot stop the suffering but can understand it, and in understanding redeem it.

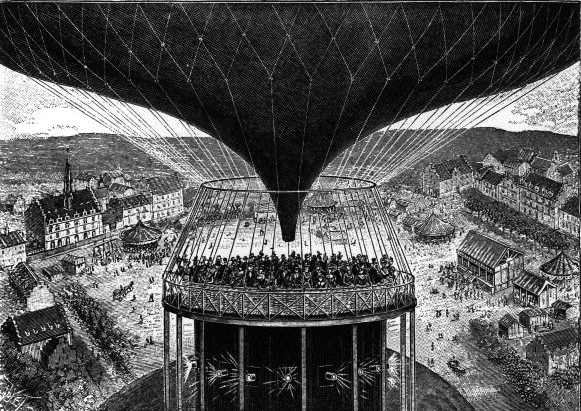

THE FAIRY ELECTRICITY

Electricity, which was already transforming society and clearly heralded even greater changes in the years to come, was treated at the 1900 exposition as a kind of Alladin's lamp, a fairy force whose chief attribute was its ability to charm the eye. A large number of exhibits harnessed electricity for the purposes of fostering illusion. The most important one was the cinéorama, which demonstrated the first attempts to synchronize phonograph recordings with the newly-developed moving pictures. But fear of fire — there had been a tragic calamity in a movie house only several months before — caused this most innovative exhibit to be closed after only a few days.

“10 synchronized 70mm movie projectors projecting on a full circle screen while we stand in a large hot air balloon basket and feel that we are floating above France. Some drawings indicate there might have been movement to simulate the balloon riding the winds, but few people actually experienced it, as the projectors created so much heat that the fire department shut the show down immediately.” — Gary Meyer, eatdrinkfilms.com

The major pavilion to symbolize the new era was the Palace of Electricity and the Water Chateau — two buildings in one. Here is the breathless description in the Hachette Guide of the fairy palace as the guiding force behind the exposition exhibits:

The Palace of Electricity's imposing facade joins the two avenues of pavilions on the Champ de Mars. The facade is composed of nine bays covered with stained glass and delicate translucent ceramic decorations. At the center is a scroll stamped with the unforgettable date: 1900. At night the entire facade is illuminated by 5,000 multicolored incandescent light bulbs, eight monumental lamps of colored glass, and lanterns sparkling on the pinnacles and along the upper ramps. In the evening this openwork frieze a a veritable luminous embroidery of light and shifting colors. Crowning the Palace is a chariot drawn by hippogryphs, The Spirit of Electricity, which projects showers of multicolored flames. 17

So far, the Hachette Guide might be describing any of the several pavilions of illusion that were common stock at exhibitions for the past decade. But no: this facade of hippogryphs and kaleidoscopic embroidery housed the power of the exposition:

This enchanted palace contains the living, active soul of the Exposition, providing it with movement and light. If, for any reason, the Palace of Electricity comes to a halt, the entire exposition comes to a standstill.18

The Palace of Electricity and Water Chateau (Click the image for a lightbox view)

Night Illuminations (Click the image for a lightbox view)

The Water Chateau fully symbolized the contradiction at the heart of the 1900 exposition. As a force, electricity deserved a statement every bit as direct and powerful as Rodin's treatment of the power of thought. But instead, the power of electricity was given a cabaret setting — made to sparkle and shimmer, arrayed like La Parisienne in jewel-encrusted robes. For observers like Paul Morand, it might seem that electricity is "the religion of 1900." But in fact, he continues, with its "orchestrations of liquid fire and debauches of volts and amperes," the nearer comparison is with drugs: "Just like morphine in the boudoirs of 1900, electricity triumphs at the exposition."19 Electricity is an aesthete’s religious experience. It proceeds by an overwhelming of the senses, and not by inducing transcendence in the viewer.

There was one visitor, though, for whom electricity provided something closer to a religious experience more traditionally defined.

THE DYNAMO AND THE VIRGIN

In his unending quest for understanding, the American humanist Henry Adams visited the Exposition of 1900. His puzzlement over the meaning of the whole experience he set forth in a classic chapter of his autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams. What bothered him about the controlled forces locked in the huge, silently-humming dynamo was their apparent affinity with the power of the Virgin Mary during the Middle Ages — a power that inspired centuries of active belief engendered in the great Gothic cathedrals. Speaking of himself in the detached third person, Adams felt:

To Adams the dynamo became a symbol of infinity. As he grew accustomed to the great gallery of machines, he began to feel the forty-foot dynamos as a moral force, much as early Christians felt the Cross. The planet itself seemed less impressive, in its old-fashioned, deliberate, annual or daily revolution, than this huge wheel, revolving within arm's-length at some vertiginous speed, and barely murmuring -- scarcely humming an audible warning to stand a hair's-breath further for respect of power -- while it would not wake the baby lying close against its frame. Before the end, one began to pray to it; inherited instinct taught the natural expression of man before silent and infinite force. Among the thousand symbols of ultimate energy, the dynamo was not so human as some, but it was the most expressive.20

Dynamos in the Gallery of Machines

For Adams the humanist, there was an analogy in the history of Western Civilization: "the nearest approach to the revolution of 1900 was that of 310, when Constantine set up the Cross." In the eyes of the planners, the 1900 exposition summed up a great century of the achievements of Progress and renewed hopes for Peace. The decorative style of every pavilion of art or industry, French or foreign, celebrated the culmination of past traditions. But Adams was looking for omens, not proclamations. The crowds could gape at the dazzling displays of orchestrated light at the Water Chateau, the Trocadero fountain, and the Eiffel Tower. Adams felt the power of the motive force that gave energy and life to the exposition. He had searched for the meaning behind the exhibits devoted to automation, sound-synchronized film, x-rays and wireless telegraphy. What he found was more than education and entertainment: it was a statement of "moral force." The silent song of the dynamo was the cantata, the logic of circuits the potential transubstantiating power, of the coming era.

The god Progress must have been pleased that at least one of the 51 million worshipers at his first exposition universelle of the twentieth century had recognized his potential.

AMUSEMENTS AND ILLUSIONS

But Adams’s response is the exception. He was determined to draw out the lesson of electricity — draw it out from the overwhelming size and number of exposition exhibits. For most, the exposition was a grand amusement park. Colonial exhibits were staged, not so much to show the usefulness of the colonies to France — this was taken for granted — but to give "civilized" visitors a chance to wander through a Dahomean hut or an Egyptian street in safety. All the colonial buildings — from Senegalese dwellings to Indochinese temples — were designed by French architects, who could allow their talents to play with "native" forms in an attempt to recreate the ambience of the colonial peoples for Westerners.

Some of the most popular exhibits at the exposition were those which gave visitors an illusory trip to remote lands. The Transsiberien was a large building in which spectators at in simultade railway cars while a long, painted canvas depicting the sights from Peking to Moscow rolled by. The Maréorama gave visitors such a convincing simulation of a seavoyage from Villefranche to Constantinople that many visitors got seasick from the rocking of the boat.

1900 Scientific American illustration of the Marjoram (Click here for a larger image)

For a steadier experience, visitors could enter the "Tour of the World," located at the base of the Eiffel Tower. The painter Louis Dumoulin created a vast living performance of the sights of nature and indigenous cultures throughout the world:

Huge public ceremonies took place throughout the exposition. The urge to reconcile Paris with the provinces gave rise to one of the most talked-about extravaganzas of the entire exposition: the Banquet of Mayors. On September 22, 606 tables were set up in tents all along the Tuileries Gardens. 20,777 mayors, from virtually every village, town, or city in France, sat down together to feast and toast the exposition. Service was provided by waiters in automobiles that rattled up and down the aisles bearing choice wines and deftly-prepared dishes.

The Banquet of Mayors was only the most spectacular instance of what had become a national institution. In Paris of la belle époque, wrote the American historian Roger Shattuck, "the banquet had become the supreme rite. The cultural capital of the world, which set fashions in dress, the arts, and the pleasures of life, celebrated its vitality over a long table laden with food and wine."[8] In some respects, the entire exposition could be seen as a mammoth multi-sensual banquet, spread out for all the world to admire and enjoy. In spite of all the differences among the provinces of France, in spite of all differences among the nations of the world, everyone could gather together peaceably at the exposition universelle celebrating the new millennium. The public spectacle, descended from the court spectacles of the 17th and 18th centuries, were now democratized and monumentalized for political purposes.

THE BALANCE SHEET

By the end of the exposition, France could congratulate herself on having hosted the most successful exposition ever staged. Though the attendance figures fell short of the expectations — 60 million visitors was the figure the commissioners expected — the results (51 million) made it easily largest attendance of any exposition. There were more than 83,000 exhibitors, and over 42,790 prizes of various degrees awarded. The 127 congresses had attracted over 80,000 participants, and renewed the reputation of Paris as the meeting place of the world. Paris herself had shown the world that the city was in the forefront of technological innovation. The Métro, the Gare d’Orsay, and the Pont d’Alexandre opened with the exposition, and the city was richer by two major exhibit halls — the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais — as a direct gift from the exposition itself.

Yet, in spite of all the statistical triumphs, the exposition of 1900 marks the end of an era. The industrial exhibits, the architecture and the art of 1900 symbolized more of a summary of the nineteenth century than an augury of the twentieth, except insofar as technology promised to be a major force in the entertainment industry. The exposition of 1900 was much more a world’s fair than an exposition. The social and technological idealism were there in 1900; but the fervor, the intensity of conviction, were nowhere near the level they were during the first four universal expositions.

The exposition universelle of 1900 proved to be the last of its kind held in France. Of the three world’s fairs to be held in Paris later, two were theme expositions — decorative arts and colonial possessions — and the third, significantly, was called an "international" exposition. The mood and the context for such events had changed, and France could never again capture the spirit that had led her to proclaim her first three expositions "universal."

NOTES

1 Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900 à Paris: Actes organiques (Paris, June, 1896, page 1)

2 Quoted in Philippe Jullian, The Triumph of Art Nouveau, page 23-24

3 Many, many books have been written about the Dreyfus affair, so quickly summed up here. For a somewhat fuller sketch of this infamous incident, placed in the context of the Parisian world's fairs, see Marshall Dill's Paris in Time (New York, 1975), "Crises and World's Fairs," pages 277-279.

4 Jullian, The Triumph of Art Nouveau, page 66

5 Frederic Mayer, The Parisian Dream City (St. Louis, 1900), n.p.

6 Ibid.

7 "L'Exposition de 1900," in L'Eclair, June 18, 1895

8 Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I (New York, 1955), page 3. It should be added that Shattuck was no admirer of the great exposition, which he dismisses as an extravaganza when "Paris looked and acted like an overblown Venice" (page 17).

9 Revue des deux Mondes, November 15, 1900.

10 A term either coined or popularized by André Hallys in his "En flanant à travers l'Exposition de 1900, in Recueil d'articles publiés (Paris, 1901), n.p.

11 José de Olivares, in The Parisian Dream City (Saint Louis, Mo., 1900), n.p.

12 Quoted in Jullian, op. cit., page 43

13 ibid., p. 43

14 "Ne vous arretez pas, Monsieur le Président. C'est ici le déshonneur de l'art français." Many authorities quote this remark, but no one seems able to locate its source. Gerald Ackermann cites it in his excellent monograph Jean-Léon Gérôme, and it is used as the lead quotation in Le Livre des Expositions Universelles, 1851-1989 (Paris, 1983), page 117.

15 Letter written to Robert Ross, July 7, 1900

16 Cléo de Mérode, Le ballet de ma vie (Paris, 1955), page 88

17 Hachette Guide (Paris, 1900), n.p.

18 ibid.

19 Paul Morand, 1900 (Paris, 1900), pp. 68 and 69

20 The Education of Henry Adams, Chapter 25

An interesting contrast between Henry Adams's reaction and the attitude toward technology today (2015):

"Henry Adams’s dynamo has been replaced by Everyman’s iPod, and awe has given way to complacence and dependence. Your computer’s e-mail program doesn’t inspire awe; it is more like a dishwasher than a dynamo. Nineteenth-century rhapsodies to the machines that tamed nature, such as the steam engine, have given way to impatience with the machines that don’t immediately indulge our whims." -- Christine Rosen, http://incharacter.org/features/awe-and-the-machine/

Statistical Appendix

Opening Date: April 15, 1900

Closing Date: October 15, 1900

Size of site: 543 acres

Official Attendance: 50,860,801

Exhibitors: 47 nations

Expenses: 116,000,000 francs

Receipts: 74,000,000 francs

Loss to Government: 42,000,000 francs

Top Officials: Alfred Picard, Commissioner General

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Henry. The Education of Henry Adams

Barin, Gustave. Après faillite: Souvenirs de l'Exposition de 1900 (Paris, 1902).

Bergeret, Gaston. Journal d'un nègre à l'Exposition de 1900 (Paris, 1900).

Champier, Victor (editior). Les industries d'art à l'Exposition universelle de 1900 (Paris: 1902).

L'Exposition de Paris (1900) publiée avec la collaboration d'écrivans spéciaux et des meilleurs artistes, 3 volumes (Paris, 1900).

Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900 à Paris: Actes organiques (Paris, June, 1896).

Figaro Illustré, L'Exposition de 1900, numbers 110-128 (Paris, 1900).

— Les Sections Etrangères à l'Exposition de 1900 (Paris, 1900).

Geddes, Patrick. "The Closing Exhibition — Paris 1900," in The Contemporary Review, November, 1900, pages 653-668.

Hallays, André. "En flanant à travers l'Exposition de 1900," in Recueil d'articles publiés (Paris, 1901).

Jullian, Philippe. The Triumph of Art Nouveau: Paris Exhibition 1900 (London, 1974).

La Sizeranne, Robert de. "l'Art à l'Exposition de 1900," in Revue des deux Mondes, several essays, May-October, 1900.

Lockroy, Edouard. "L'Exposition de 1900," in l'Eclair, June 18, 1895.

Mandell, Richard. Paris 1900: The Great World's Fair (Toronto, 1967).

Mayer, Frederic. The Parisian Dream City (St. Louis, 1900).

Morand, Paul. 1900 A.D.,translated by Romilly Fedden (New York, 1931).

Peck, Ferdinand. Report of the Commissioner-General for the United States to the International Universal Exposition, Paris, 1900, 6 volumes (Washington, D.C., 1901).

Picard, Alfred. Rapport général administratif et technique, 8 volumes (Paris, 1902).

— Le bilan d'un siècle (1801-1900), 6 volumes (Paris, 1906).

Shattuck, Roger. The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I (New York, 1955).

Vogüé, Eugène-Melchior de. "La défunte Exposition," in Revue des Deux Mondes,November 15, 1900, pages 380-399.

Here is my account of the historical background for the Paris expositions