The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1878

by

Arthur Chandler

Expanded from World's Fair magazine, Volume VI, Number 4, 1986

Watercolor sketch, by H. Clerget, of the opening day of the exposition, May 1, 1878

(Click here for more images of the main exposition buildings)

PRELUDE

It was a gloomy beginning for the new French Republic's first universal exposition. On opening day, May 1, 1878, dark clouds gathered over Paris. As President Marshall Macmahon's cortège assembled for their festive march to the exposition grounds, thunder rumbled and the rains rushed down. As the procession approached the fairgrounds, the downpour stopped and the sky lightened — but only for a few minutes. The rains began again, and thousands of umbrellas sprouted along the Champs Elysées.

But the ceremony maintained its dignity. The crowd cheered wildly to see the leaders of the Republic marching as regally as any Bourbon or Bonaparte. While the president and his party strode forward majestically, workers unrolled a rich red carpet all the way to the exposition grounds. The sight of the triumphal march of the president's delegation was so impressive that only a few observers noticed, a hundred yards or so in advance of the party, another crew of workers frantically dumping barrels of gravel into the muddy roadway, so that the carpet and Monsieur le President would not sink into the mire on the way to the great ritual of Technological Progress.

In the broad esplanade of the Trocadero park, the orchestra played Charles Gounoud's Vive la France, composed especially for the occasion. President Macmahon made a stirring speech; and just as he declared France's third exposition universelle officially open, the rain ceased. As the heavens lightened over Paris, throngs of people cheered the president, the exposition commissioners, France, and themselves. Multicolored banners streamed from the windows all over the city. Traffic was jammed, unable to move; but nobody seemed to mind. "There was a block of carriages in all the principal thoroughfares," wrote a British correspondent to the fair, "but the greatest content and hilarity prevailed. The weather had cleared, and the gay city of Paris once more justified its name."1

Seven years after "the terrible year"of 1870-71, France was ready to transcend the Franco-Prussian war and the Commune Revolt. To forget those tragic years would be impossible. But, to the leaders of the Third Republic, it was equally impossible for France to remain an object of pity and scorn, a has-been power with no sense of national purpose. The 1878 exposition universelle was a proclamation, to the nation and the world, that France was ready once again to assume her traditional role as a great civilizing force in human culture. "The time had come," wrote Alfred Picard, "for France to lift the veil of sorrow and mourning, and to invite the world to a public festival."2

BETTER THAN THE EMPIRE

"The advocates of monarchy have always been boasting of the fetes of the Royalty and the Empire," wrote the staunch republican Francisque Sarrey. "Well, here are the fetes of the Republic. Are they less worthy than the others?"3 Throughout the journals and official reports of 1878, there runs a common theme: whatever the Empire did, the Republic can do better.

Had the 1867 Exposition covered the Champ de Mars (setting the precedent for holding every subsequent French exposition universelle in that location)? Very well, then the 1878 Exposition would not only dominate the Champ de Mars: it would make over the Trocadero Hill (which had been a refuse dump for the 1867 exposition) into a glorious festival palace, thereby including the River Seine into the exposition grounds. For the designers and commissioners of the event, the very scale of the 1878 exposition called attention to the greater aspirations of the Third Republic.

Did the 1867 exposition invent a novel twofold classification system for all exhibits, dividing them by the nature of the products and the nation that made them? Very well, then the 1878 exposition would improve on that scheme, and give it a more efficient spatial arrangement by laying out the exhibits in a rectangular plan. The commissioners were willing to appreciate and adopt good ideas from the Second Empire. But even a good idea can be improved upon; and the rectangular organization of exhibit space proved to be much more realistic than the elliptical arrangements of the 1867 building.

Overview of the plan for the 1878 exposition (click the image for a larger view)

Detail of the main exposition plan (click the image for a larger view)

Did the Empire's exposition feature a working model of the renowned (and French) Suez Canal? The Republic's exposition would put the hydraulic principles of the canal to work in the very grounds and exhibits of the fair itself. The world would see that France knew how to adapt the principles of engineering to a wide variety of uses and locales.

Did the 1867 exposition commissioners offer space for international cuisine and an outside park for housing the large exhibits that could not be included in the main building? Then the 1878 exposition would offer the same allurements, but with a "Street of Nations" that would give an ordered grandeur to the exhibits of the participating countries. Internationalism would be given a better and more ordered showing than it had received in 1867.

The exposition commissioners were more than willing to learn from the successes of the 1867 exposition. Jean-Baptiste-Sebastien Kranz had designed the oval Palace of Industry in 1867. Splendid achievement — but not without its flaws. The Republican Government called upon Monsieur Kranz to direct the entire 1878 exposition. Let him outdo himself in the service of the Republic!

Senator Krantz, Commissiiner General of the 1878 Exposition

Comparisons with the 1867 exposition were everywhere. Newspapers reported with pride that, in the first nine days of the 1867 exposition, there were 38,363 paid visitors. But after nine days of the 1878 exposition, 258,342 had paid to see the wonderworks of the Third Republic's fair. Even when, at the close of the exposition, it became apparent that the event would lose money, most people and government officials agreed that the price paid for the confirmation of confidence in the new Republic was not excessive.

There were dissenting voices, however. Some critics cried out that the exposition was a monstrous extravagance that France could ill-afford at the time. The country had paid off its five-billion franc indemnity to Germany only a few years previously. The money, they argued, should not be gouged out of the French people just to prove that the Republic could outdo Napoleon III as an international host. France had lost money on the 1855 exposition, as had Austria in 1873 and Philadelphia in 1876. A substantial loss in 1878 could force the French government to cut essential services in order to pay off the debt of the exposition.

Members of the clergy also objected strongly to the exclusion of religious ceremonies from the exposition. The Empire expositions had always been opened with a religious ceremony. The Republic, taking its first steps to separate affairs of government from the power of the Church, pointedly refused to include any religious statement, implicit or explicit, in the opening ceremonies. Adrien de Valette, an able writer and defender of the prerogatives of the Church, excoriated the 1878 fair as "The Exposition without God." In a widely-read pamphlet, Valette thundered against the Exposition Committee in tones worthy of Jeremiah:

When the hand of God is withdrawn from a nation, the decline of its power and prosperity naturally follows. The edifice of its past glory, constructed with many pains, crumbles away before the attacks of iconoclastic demagogues, before the efforts of the black band of materialists.4

Many parish priests told their congregation to stay away from this "atheist exposition" — a prohibition which perhaps contributed to the lower-than-expected final attendance figures and the financial loss suffered by the 1878 fair. The Church detected — rightly — that the removal of religious ceremonies from the functions of the exposition signified one more step in the assumption of religious status for industrial Progress. The interior spaces of the exposition buildings were called the "nave," "transept," "narthex" — terms exclusively associated with religious structures. The tone of the opening and closing ceremonies, and of the introductions to the official exposition catalogues, often appropriated religious terminology in the praise and blessing of the events. Now religion itself was banished — banished, at least, as an institution whose official blessings and sanction were an important part of the ideology of the expositions themselves. As we shall see, proponents of the Eiffel Tower were even more aggressive in banishing the voice of religion from the realm of Progress.

THE IRON HORSE AND THE GOLDEN CALF

If the 1878 Exposition Universelle was to be a success, then it would have to achieve its goals in spite of the sneers of royalists and the curses of priests. The exposition committee, though, had full confidence that the combined talents of French industrialists and artists, financiers and workmen, could make the event a triumph in spite of opposition. France had, after all, participated honorably in the Vienna Exhibition in 1873, and in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. Here, on home ground and in the service of the new republic, the talent of French art and science would once again dazzle the world.

In the 1878 fair, more than any previous exposition, engineering was married to art. Visitors who toured the exposition grounds before opening day were surprised to see a miniature railroad built underneath the Palace of Industry and the Trocadero Palace. These trains greatly accelerated both the building process and the removal of debris after the exhibition closed. Before the fair opened, the tracks and cars were covered over with planking. Visitors were amazed to learn that, wherever they went in the Palace of Industry, they were walking ten feet over a hidden railway.

But the greatest feat of engineering at the 1878 exposition universelle was the virtuoso control of water. Four gigantic hydraulic pumps fed the waters of the Seine through 23 miles of cast iron and lead pipe to all corners of the exposition. First the water surged up to the summit of Trocadero Hill and into the Palace towers, where it powered elevators so swift that speedometers were mounted on the walls to show astonished passengers the velocity of their ascent and descent. Some of the waters then flowed over the top of a pond that was elevated and supported by three arches in front of the Trocadero Palace, plunged down 29 feet into a fountain, then glided over terraced steps into a large basin. Another pipe carried water more swiftly beneath the earth, then launched towering, 62-foot high jets that flanked the central fountain like liquid pillars. Still another pipe carried water in a quiet, constant pulse to the aquarium in the Trocadero Park.

From the basin, the water flowed down again through the iron and lead pipes, surged beneath the Seine, then emerged quietly in peaceful ponds in the Champs de Mars. Other pipes carried water silently beneath the floorboards of the Palace of Industry, and kept the building several degrees cooler than the outside air, even on the warmest days. The harnessing of the Seine to elevators and fountains, aquarium and air conditioning, the orchestration of the force of water to unite the river with the Palace of Industry on the left bank and the Trocadero Palace on the right — this was the triumph of French engineering at the 1878 exposition universelle. Hydraulic engineering could be applied to the extension of the colonial empire (as with the Suez Canal), or to the refreshment of decorative ponds. The best technological innovations were those which had both heroic and domestic applications — the greatest good for the greatest number once again.

Water pipes for the fountains, elevators, and air conditioners at the 1878 Exposition

Some visitors, though, saw another, more frightening apparition by the waters of the Trocadero Fountain. Word had gotten back to the provinces that people were coming from all over the world to worship a golden calf in Paris! Parish priests all over the country took these rumors as signs that God had indeed forsaken the capital city, and the judgment day was surely at hand. When journalists got wind of the story, they searched for many a day to discover the source of the tale. They found it by the Trocadero fountain. There, at one of the four corners of the basin, was an immense gilded iron sculpture of a bull, cast by the sculptor Auguste Cain. French peasants, seeing the crowds gathered around this plated beast, had assumed that it had been set up for worship by the godless exposition authorities.5

Auguste Cain's "Golden Calf" (1937 photograph)

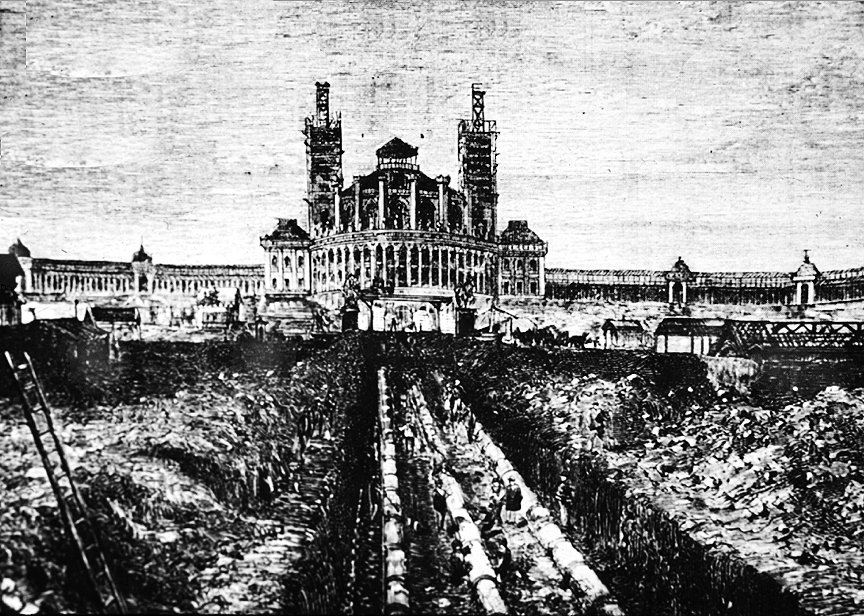

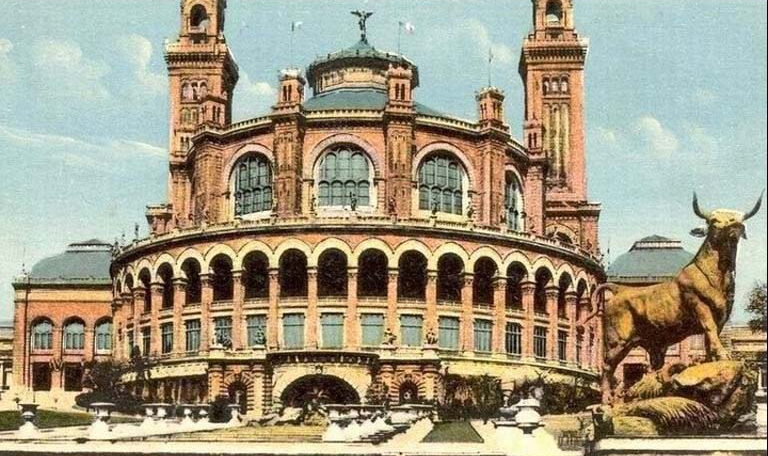

THE PALACE ON THE HILL

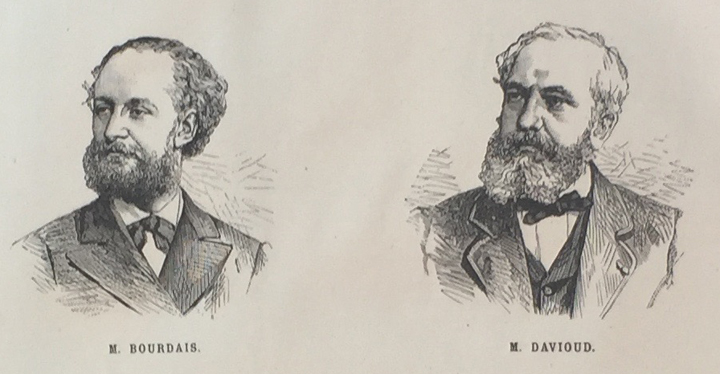

Not all the hydraulic virtuosity of France could redeem the Trocadero Palace, designed by Gabriel Davioud and Jules Bourdais. Davioud, the chief architect of the Trocadero building and fountains, had worked with Baron Haussmann during the glory years of the Second Empire and was serving, at the time of the exposition, as the inspector general of architecture for the city of Paris. He helped create the landscaping of the Bois de Boulogne and the Parc Monceaux. Several squares, gardens, and fountains in Paris were Davioud's handiwork. His touch with plants and water was deft and sure. But his talent did not redeem the Trocadero Palace. Even to contemporary observers sympathetic to eclecticism in architecture, Davioud's pastiche of Romanesque columns, Spanish-Moorish arches, the Giralda Tower and polychrome decor was an unqualified failure. The wide sweep of the two flanking colonnades was impressive enough; but the Trocadero palace itself looked squat and proportionless. Parisians put up with the building for 56 years before demolishing it to make way for the Chaillot Palace at the 1937 exposition.6

Architects of the Trocadero Palace

The dimensions of the Trocadero were conceived in such a way as to make it evident that modern technology could surpass the venerable monuments of traditional architecture, and that French builders could once again outdo the English. The size of the main auditorium surpassed those of its English competitor, the Albert Hall. The dome of the Trocadero was some twenty-three feet higher than the dome of St. Peters, and the flanking towers overtopped the height of Notre Dame’s tower by forty-five feet. This the beginning of the audacious humbling of great religious monuments — a movement that would culminate eleven years later in the Eiffel Tower.

In spite of its pretensions to grandeur, the building seemed cursed even before its completion. It was unfinished on the opening day of the exposition, even though over 800 workers labored diligently for a year on the building and its site. Even when the exterior was finished and the internal exhibits mounted, the opening day of the music festival had to be delayed because the grande salle des fêtes was still not finished in June. Then, less than a month after the concert hall was finished, a careless workman left a water tap running all night on one of the top floors of the building. The ceiling of the hall was damaged; and once again, the music festival had to be delayed.

When the difficulties were cleared up, however, the Trocadero quickly became a major center of cultural activity at the Exposition. The concert hall itself was glorious, even if the vast space became a sea of echoes during the performances. This was an epoch that loved the grand gesture in art and life; and the Trocadero auditorium was a fitting realization of the era's delight in colossal effects. Concerts were held almost every night; and the main hall, which held 4,500 people, was usually filled to capacity. On the walls, 4,500 gaslights made every musical performance a visual spectacle as well. The sights and sounds of the International Choral Competition, in which thousands of singers at a time performed before thousands of spectators, were among the most overwhelming events of the entire exposition.

Trocadero Concert Hall (click the image for a larger view)

Taking up several other large rooms in the Trocadero was the retrospective exhibit. Here visitors could see choice works of decorative art culled from government and private collections all over France. Arms and armor, crowns, fans, metal and woodwork, Sèvres porcelain — over a thousand years of French craftsmanship was gathered into a single show, which continued for several months after the exposition itself was officially closed in November.

In other halls of the Trocadero Palace, members of the international conferences discussed a wide range of topics. The International Congress on the Rights of Women featured discussions and debates on the place and rights of women in all phases of society. There were technical conferences for engineers and psychologists; gatherings of Alpine climbers, meetings for "discharged prisoners' friends," sessions on gas-tar, a convocation of the International Peace Congress. One congress even had to take up a problem created by the world's fairs themselves: how to deal with dishonest manufacturers who falsely advertised medals claimed to have been won at international exhibitions.

Some of the meetings had immediate and far-reaching results. Victor Hugo led the Congress for the Protection of Literary Property, which led to the eventual formulation of international copyright laws. Similar congresses dealt with the problems of protecting industrial property, and of governing the rights to reproductions of works of fine art. An international postal union was established, at a conference held in Paris while the exposition was taking place, to facilitate communication by letters among the nations of the world. The International Congress for the Amelioration of the Condition of Blind People led to the world-wide adoption of the Braille System of touch-reading. By incorporating these meetings into the official agenda of the exposition itself, the Commissioners were consciously attempting to offset the charges of frivolousness that had been leveled at the 1867 Exposition. In 1878, not only objects, but ideas themselves were on display. "There is a clear analogy," said the official report of the congresses, "between the work of the congresses and that of international expositions themselves: in the latter, people exchange products; in the former, people exchange ideas."7 The congresses of the 1878 exposition continue and expand the work of its predecessors by giving international issues a focal place for people to meet and recognize the universal nature of their concerns. As long as, for example, women from France and women from America worked in isolation for the extension of the vote, there could be little or no sense of solidarity. Brought face to face with people from many nations, all of whom shared their concerns and their determination, women could return home with a renewed sense of the global (or, at least, Western cultural) scope of their beliefs.

THE TROCADERO PARK

Sloping down from the Trocadero Palace to the Seine was the Parc. Here visitors could find restaurants, an aquarium, and some of the foreign pavilions too large to fit into the Street of Nations inside the Palace of Industry. The Parc on Trocadero Hill was the 1878 exposition's answer to the 1867 exposition's open-air amusements and outdoor exhibits. At the 1878 exposition, any nation that felt it had been given too little space in their main exhibit off the Rue des Nations could construct a secondary structure here in the Trocadero Park. There were fewer such outlying buildings at the 1878 fair than in the 1867, since this time most nations were given space for their architectural statements on the Rue des Nations inside the Palace of Industry. But there was still the same arbitrary, scattered quality about the placement of structures on the grounds: a Japanese farm wedged incongruously between an Egyptian temple and a Spanish restaurant; a Norwegian clock tower striking the hour over potters in an Algerian village where women made pots using ancient Etruscan techniques. Here China and Sweden shared a common terrain, but little else.

The Park structures did have their pleasures and uses, however. The Japanese delegation, for example, used its "model farm" in the Park to host a dinner for the European commissioners. One British commentator treated the whole affair with the condescension befitting a man of empire. He scoffed at the "toy farm" with its "Lilliputian plates and saucers" and tea "drunk out of thimbles." He concluded his review with the observation that "the Japanese seem to live upon about enough rice for a bird."8 But the Japanese went out of their way to be polite to foreigners. Chairs and forks were brought for the comfort of their European guests. One writer at the Exposition recalled a similar circumstance when a group of French officers had been feasted by the Chinese:

"I can't tell what I'm eating, with all the bones taken out," remarked a French officer at the table.

"Yes," replied his host,"we do our butchering in the back room."

A little later the same officer asked why the Chinese did not use knives and forks like all other people.

"We did," replied the host," before we were civilized." 9

Chinese pavilion at the 1878 exposition

After the exposition closed, some of the Asian and North African restaurateurs decided to stay on in their host city. Soon the exotic allure of foreign cuisine attracted Parisians from all walks of life, and became a permanent fixture of the city's growing constellation of gourmet and specialized restaurants. Just as Parisian aesthetic taste was willing to admire a certain "barbaric splendor" in non-European forms of architecture, so they expanded this same burgeoning internationalism to include the pleasure of the palette.

Bars and Buffets at the Exposition(Click the image for a lightbox view)

THE PALACE OF INDUSTRY

Facade of the main exposition building

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

Crossing the Pont d'Iena from the Trocadero Park, the fairgoer confronted Léopold-Amédé Hardy's impressive facade (constructed by Gustave Eiffel) of the main exposition building. The stark iron beams of the Palace of Industry were painted blue, and decorated with red and yellow lines. Ranged along the lower story of the entranceway and facing the Seine were twenty-two "Statues of the Powers" — allegorical sculptures that represented the twenty-two other nations that the French officially recognized as the significant forces in world affairs:

The Netherlands, Hungary, Portugal, Austria, Egypt, Spain, Persia, China, South America, Japan, Denmark, Italy, Greece, Sweden, Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, The United States, Russia, Australia, England, British India

These statues signified more than complimentary bows towards sister nations: they were explicit statements of esteem by the French government. Several important features of French foreign policy can be detected at once: South America is treated as a single nation — presumably including Mexico and Central America; Canada does not appear, nor do many African and Asian nations; India is represented as "British India" — an avowal that, even for republican France, India was reckoned important only by virtue of its status as a British colony. Most significant of all is the absence of a statue representing Germany. France was not yet willing to forgive or forget the Franco-Prussian War. It would have been too painful for the French government to erect a statue to the nation's bitterest enemy.

Europe (by Alexandre Schoenewerk) America (by Ernest-Eugène Hiolle) Africa (by Eugène Delaplanche)

The statues can be seen today on the parvis of the Orsay Museum in Paris

(Click the image for a LIGHBOX view)

Once inside the Palace of Industry, the fairgoer would see a range of displays that had by now become familiar types in international exhibitions: huge machines, elaborately decorated furniture, works of fine art — everything from cut glass to corset stays. The exhibits were organized on a modified version of the 1867 system of classification: perpendicular to the Seine, products were ordered by their nature; parallel to the Seine, products were identified by their country of manufacture.

The exhibits and their arrangement at the 1878 exposition universelle were not just modifications of the earlier fair, however. Perhaps the most innovative and most widely admired feature of the fair was the Street of Nations. In the central courtyard of the Palace of Industry, each participating nation was invited to build an entranceway to its exhibits. The result was a splendid row of facades that announced, in architectural terms, the character and aesthetic values of every nation. The Street of Nations not only gave the visitors a prelude to the exhibits within the Palace. The whole ensemble taken together allowed fairgoers to see, at one glance, the eclectic nature of the world in 1878. What a lesson, to see the Slavic sumptuousness of the Russian facade — a model of the house where Peter the Great was born — close by the quiet geometry of the Japanese entranceway! Georges Berger, Director of the Foreign Sections, was universally applauded for the planning and execution of this "international boulevard."

Japanese and Russian pavilions

Impressive as it was, the Rue des Nations would have been even more striking had the exposition commissioners been able to carry out their original plans to build a Street of France across the courtyard from the Street of Nations. Facing the foreign pavilions would have been facades from different periods of French architecture: Charlemagne, Henry II, Henry IV, Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI. The project would have involved an enormous expense, and would have involved delaying the opening of the Exposition by at least several weeks, so the idea was reluctantly abandoned.10

In spite of their constant looks backwards top the expositions of the second Empire, the commissioners of the 1878 exposition did not include one element that was such a strong moral point of the previous two fairs. In 1878, there was no special category for inexpensive goods. In this respect, the exposition of the Third Republic lacks something of the social idealism of its predecessors. The official reports make it clear that the goal of the exposition is more to advance technology than to propose social theories under the guise of Utilitarianism.

THE TRIUMPH OF AMERICA

An astute observer who had attended the 1867 exposition universelle might have detected some subtle but decisive changes in the nature of the exhibits. The steam engines and the decorative arts still dominated the 1878 exposition, as they had in all previous world's fairs. But now there were a number of smaller machines whose ingenuity and potential for universal usefulness captured the imagination of the public even more than the metallic monsters that hummed and banged in the heavy machinery section. One booth featured the first personal printing machine: the typewriter. Another display featured a novelty that promised to make carriage rides more endurable: rubber tires. And in the American section, visitors could marvel at a staggering array of personal appliances.

In the arena where entrepreneurs sought to make small machines available to the widest possible audience, the Americans were clearly emerging as the leaders. Typical was the American dominance in the sewing machine business. The Wheeler and Wilson Sewing Machine Company repeated its performance at the 1867 exposition by winning the grand prize in its class, amidst universal praise of the fine workmanship and versatility of their products. The Singer Company was demonstrating its sewing machines for home use, and announcing its multinational distribution networks (over 280,000 machines had been sold in 1877). An American watchmaking assembly line demonstrated the virtues of standardized parts in mass production. Still another booth featured a semiautomatic bootmaking machine.

Some Europeans looked with condescension on American enterprise. All this scurrying about to produce heaps of articles — what was the point?11 One English critic openly mocked "those bright devices our cousins across the Atlantic are throwing off one after another to save time, if it is only a second."12 Such writers could not foresee the tremendous impact that standardized parts and assembly line production would have on national and international economics. But they might have paused to reflect on the appropriateness of such a technology coming from a democracy that had pledged to give everyone a fair chance to acquire such products as would ease their labors.

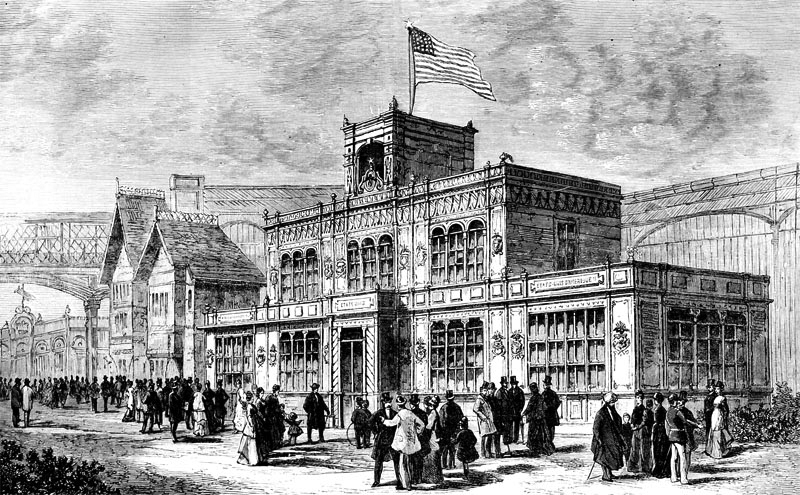

The French leveled the same kind of complaint at the American pavilion on the Rue des nations. Here, remarked Paul Sedille after praising the British pavilion:

What a contrast with the pavilion of the United States! A railway station, a bathhouse, a police precinct? It is difficult to say just what it is. In any event this construction, fabricated out of wood, has no pretensions of solidity or monumental durability. It seems to offer merely a specimen of wooden skeletons quickly transported and put up like an instantaneous creation of some new villa by some unknown lakeshore. It is not even a scaffolding. It's more like something a carpenter slapped up with the sole object of doing the job quickly and cheaply." 13

The American Fine Arts Commissioner, William W. Storey, sadly concurred. "We did save money; we did save time; but we lost credit. We went to a great international reception in our shirt-sleeves." 14

American pavilion, 1878 exposition

But the hosts of this great reception found the American barbarity of taste redeemed by vigor of invention. The most dramatic embodiment -- for Europeans, and especially for the French -- of this quality of technological enterprise was Thomas Alva Edison. Edison was hailed as a universal talent who had grown up with no formal education, no advantages of aristocratic privilege or patronage. For the French people, who were still working through the first, tentative stages of their Third Republic, Edison symbolized the potential of human genius unhampered by artificial social constraints. Historian Raymond Isay has accurately assessed what Edison meant to the world in 1878:

Self-taught engineer, savant who remained a worker, the train-boy become a millionaire, Thomas Alva Edison . . . with him, a new ideal of civilization comes to the people; an ideal on which the three most powerful myths -- mystiques! —of the modern age are based: the American myth, the myth of democracy, and the myth of science.15

For the hard-of-hearing, Edison had invented the megaphone. Fairgoers were astonished to hear how sound could be amplified with Edison's device. "This instrument," he told them, "can be placed on the knees of a deaf person in a theater, and the sounds can be intensified in the proportion of one to fifty, in the same manner as an opera glass intensifies the view."16

Even more acclaimed was the phonograph. The recording machine on display at the 1878 exposition was a simple mechanical device that used a mouthpiece for activating a notched disk which in turn made indentations for playback on tinfoil wrapped around a brass cylinder. First shown at the Philadelphia Exposition two years before, this device sent European journalists into ecstasies. In 1877, Edison showed his machine to British audiences, where they heard "God Save the Queen" sing forth from the strange device. One Parisian gazette even predicted — perhaps with malice ? — that the phonograph would render useless the tenors of the opera. A. Bitard wrote that some people in the audience at the phonograph booth suspected a trick — ventriloquism. But when the skeptics were finally satisfied that the device was authentic, people enthusiastically predicted marvelous uses for the phonograph. It could be used to teach foreign languages, said Bitard, by having speakers record equivalent French and English phrases for learners to hear and master. Edison himself had wide ambitions for his brainchild:

Here, you see, is a book for the ignorant, who have never learned to read. It will be used to make toys talk. . . It will be used by actors to learn the right reading of passages. In fact,its utility will be endless.17

One writer for L'Exposition Universelle de 1878 summed up the potential impact of this machine by comparing it to the two other great advances in communication of his century:

If space has been conquered by the telephone — as it has already been conquered, in a different fashion, by the telegraph — it is time that is conquered by the phonograph.18

The Edison Phonograph listening room, here at the 1889 exposition

Also on display was a telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell and improved by Edison. Though he was not the principal inventor of the telephone, Edison's improvements so dramatically enhanced the performance of this revolutionary new communications device that one commentator termed the display "a glorious triumph for Edison." It is a fair indicator of Edison’s prestige that, in spite of the fact that the telephone was not his invention, he shared almost equally in the glory of its presence at the exposition.

Speaking and listening at the telephone pavilion -- stereophonic listening on the telephone would return with cel phones earbuds a century later

But for all Parisians and visitors to the fair, the most dazzling display of Edison's genius came in June of 1878. Electric lighting had been installed all along the Avenue de l'Opera and the Place de l'Opera. And when the switch was thrown, flooding these famous places with a brilliance that no gaslight could achieve, Edison's triumph was complete. The Wizard of Menlo Park had changed forever the very complexion of the night!

The three inventions associated with Edison — the phonograph, the electric light and, to a lesser extent, the telephone, all fulfilled what most fairgoers wanted from technology: sweeping, dramatic, and immediately useful improvements to their daily life. Hydraulic engineering for fountains or a canal was all very fine; but an invention that allowed them to capture and play back sound, to illuminate the streets and interiors of their houses, to speak with others across town or across the world — these made immediate sense to the millions who lined up to see and admire the work of the Wizard of Menlo Park.

VICTORY IN DEFEAT

Though the Trocadero Palace was the fine arts building of the fair, contemporary painting and sculpture were housed across the Seine in the Palace of Industry. In fact, the 1878 exposition universelle hosted two artistic competitions: the annual salon, where French artists competed for prizes; and the exposition salon, where international artists vied with each other for medals.

For most art historians today, the 1870s are known as the Impressionist Years, when the practitioners of the new style exhibited their works in defiance of reactionary academic tradition. But even "official art" at the Exposition showed a remarkable variety. Pierre Bonnat and Ernest Meissonier were the grand old men of the show, as Ingres and Delacroix had been in 1855. Each artist had a room in the fine arts section entirely devoted to his works. Meissonier in particular was at the height of his fame; and his clever genre scenes brought enormous prices. Adolphe Bouguereau's exquisitely rendered religious and mythological scenes and Alexandre Cabanel's "Death of Francesco da Rimini" were the rage of the day. Who would have predicted, in 1878, that after a hundred years, the names of these four most prominent French artists of the day would sink into obscurity?

But the greatest public outcry of the day was not created by the Impressionists or the accepted salon entries: it was the refusal by the Exposition Committee to allow any battle scenes that referred to the Franco-Prussian War. France, at that time, was the home of a number of talented painters of battle scenes. "The organizers of the 1878 Exposition," wrote Edward Strahan,"seemed to these ambitious young painters to be pushing French politeness to the limits of the incredible when they invited the military artists to withdraw from the competition to which the rest of Europe was bidden."19

Though the German government was not invited to participate in the 1878 Exposition, German artists were allowed exhibition space. Exposition commissioners were understandably anxious to avoid an embarrassing incident that might arise from showing pictures in which French and German soldiers were shooting each other. Scenes from other French military engagements — even Waterloo — were allowed. But none of the spirited and patriotic canvasses of Alphonse de Neuville, Edouard Detaille, or several other young painters, was admitted to the Exposition salon.

Edouard Detaille, "Sale of the Hostages " -- French officials bargaining with Prussian officers for the return of wounded soldiers, 1878

The Goupil Gallery in the Rue Chaptal offered the young artists exhibition space. And what foreigners most often visited the gallery? The Germans, of course. One German artist commented that he saw nothing as good in the Champ de Mars as what he had encountered at Goupil's Gallery. Strahan aptly sums up the symbolism of the entire episode:

It was not to be wondered at that the interdiction which came to upset the young French school of military art at the moment when it was putting on its armor for the tournament of the Champ de Mars, should have aroused lively revolts. A prompt feeling of resentment sprang up in the world of the studios, and the ardent hearts of the painters boiled over with what they considered patriotic ardor. Was it not a painful insult to exclude that graphic and youthful school, so popular and so French, which had found a way to extract a kind of victory out of defeat?20

The "Goupil Incident" shows in high relief the traditional attitude of the exposition commissioners. Art must be beautiful, not painful. Art must be moral; but it should take its lessons from classical sources, not from the oppressive reality of contemporary life. Artists can depict a sumptuous Venus or a Mary Magdalene, but not a Parisian prostitute or a mind-wrecked absinthe drinker. A canvas showing Alexander the Great defeating Darius of Persia could be noble and uplifting; but a canvas showing a handful of French troops barricaded in a village church and fighting the Prussians to the bitter end — this is bad taste.

At the 1878 exposition, though, it was not painting, but sculpture that most forcibly captured the public's attention. Even some of the established graphic artists had turned to this medium. Jean-Leon Gérôme, one of the grand prize winners in 1867, exhibited some of his new mixed media sculptures at the exposition. Gustave Doré, well-known for his illustrations of Dante, Milton, and the Bible, exhibited several works, including the plaster cast of his eleven-foot high vase, "Poem of the Vine."21

Since the deaths of Carpeaux and Barye in 1875, the "throne of sculpture" had been vacant. The man who seemed destined to replace them was Marius Jean Antonin Mercié, the grand prize winner at the Exposition. His statue of Fame surmounted the Trocadero during the months of the Exposition. His Genie des Arts had already been picked to replace the statue of Napoleon III in the Louvre. But it was Mercié's Gloria Victis (first exhibited in 1874) that emerged as the one of the most popular works at the fair, and one of the most revered sculptures of the whole decade.

Gloria Victis ("Glory to the Vanquished") might serve as the theme sculpture of the entire exposition. It shows a strong yet graceful woman bearing the broken body of a fallen warrior. His sword is shattered, but his soul still raises his left arm in a final heroic gesture. The winged woman — the spirit of France — moves forward with a flying stride. Her whole countenance is firm with resignation. There is no melodramatic suffering, no whimpering at defeat. She bears her burden as she must, as France must. She is strong, and her spirit will endure.22

Gloria Victis by Antonin Mercié at the 1878 exposition

This is the kind of statement about the Franco-Prussian War that the exposition commissioners were willing to honor: idealized, classical in its narrative references and modeling technique, designed to arouse a sentiment rather than to express an emotion.22A Gloria Victis announces, in suitably symbolic terms, that France had accepted the burden of defeat, and was on the way to complete recovery.23

THE COLOSSUS OF LIBERTY

The Exposition grounds abounded with works that were emblematic of a place, a mood, or a spirit. The upper level of the Trocadero fountain was adorned with statues representing the continents; the lower level, with gilded iron statues of a horse, a bull, an elephant and a rhinoceros.24 In front of the Palace of Industry, the twenty two "Powers" stood sentinel. But in the garden of the Champ de Mars, visitors were astonished to find, not merely an oversize sculpture, but the head of a colossus that would rank as one of the wonders of the world: Auguste Bartholdi's Liberty Enlightening the World.

Bartholdi's "Liberty" symbolizes the triumph of the colossal in French art. Prince Napoleon had warned, in his final report on the 1855 exposition universelle, that future expositions should beware of attempting to outshine their predecessors. But the urge to shine more brilliantly could not be denied to any artist or nation, especially in the peaceful arena of international expositions, and most especially to a reborn French nation. After all, the designer of the 1855 Exposition Palace of Industry made it a point of honor to build a taller and more spacious building than the Crystal Palace; and the 1878 Exposition had on virtually every score compared itself — favorably, in most cases — to the Empire exposition of 1867. This urge to go one up on one's predecessors would climax in 1889 with the construction of the Eiffel Tower. And it was Gustave Eiffel himself who designed the internal metal supports for Bartholdi's Liberty. The "bigger is better" — or, more accurately, "bigger is more magnificent" — philosophy permeates all phases of the exhibits and the exposition itself.

The head of Liberty at the 1878 exposition

Every day, visitors by the hundreds lined up to travel into the head of the Statue of Liberty. There were many ways to admire the work as it loomed over the gardens of the Champ de Mars: for the splendid view it afforded of the exposition grounds; for Eiffel's ingenuity in accommodating the rigors of structural mechanics to the demands of art; for Bartholdi's skill in modeling correct and noble proportions on a scale never before attempted in art (it is still the largest sculpture in the world). But in 1878, the deepest point to ponder was what the statue symbolized about the relation between the new republic of the old country of France and the century-old republic in the youthful country of America.

France had for some time felt affectionately towards the United States. French soldiers had aided the cause of American independence; and the Founding Fathers openly modeled much of their constitutional thinking on the works of the great French thinkers of the Enlightenment. When the Second Empire was overthrown, America was the first to grant official recognition to the new republic. And even in the darkest days of the siege and civil war of 1870-71, the American diplomat Elihu Benjamin Washburne was the only ambassador of a major power who stayed in Paris throughout the turmoil.

Bartholdi's "Liberty," though, is more than a monument to the maturing friendship between the nations of France and America. It was and remains a votive statue to democracy. It is an announcement that a republic can survive and thrive — heroically, on a superlative level — in a world encrusted with despotism. Here, "Liberty" merges with the more intensely national message of the 1878 Exposition. Just as America had shown in 1876 that it was once again a nation healed and whole, a country that had overcome the tragedy of civil war and emerged stronger than ever, so France proclaimed her recovery from the twofold disaster of military defeat and civil dissension. When the Exposition lights were extinguished on November 10, 1878, the streets of Paris blazed forth with fireworks, candles, gaslights and Edison's electric bulbs. France was well.

1878 Exposition Medal by Eugène André Oudiné (click the image for a larger view)

NOTES

1 The Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, May 7, 1878, page 3

2 A. Picard, L'Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1889 (Paris, 1891), Vol. I, page 235

3 The Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, May 21, 1878, page 26

4 quoted in The Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, June 29th, 1878, page 87

5 For a full account of this misadventure, see The Chefs-d'Oeuvre d'Art of the International Exposition, 1878, edited by Edward Strahan (Philadelphia: George Barrie, n.d.). The sculptor himself, far from being offended by the incident, referred to the scandal as "the highest compliment ever paid to my work."

6 Strahan, writing in The Chefs-d'Oeuvre d'Art, simply said of the Trocadero: "It is not happy." The passage of time did not improve public opinion of this unhappy edifice. For a vicious description of the old Trocadero in 1937, see Louis Gillet's epithets in La Revue Musicale, June-July, 1937, page 99: "a fat, misshapen potbelly. . . a monstrous snail. . . a godawful amalgamation of crab, antelope, and turtle. . . a vacuous idiot with a pair of asses ears. . ."

7 Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1878, Paris. Rapports de Jury Internationale; Jules Simon, general editor; (Paris, 1880), page 134. For a complete listing of all the congresses and their topics of discussion, see the United States Commissioners' Report, Volume I, pages 455 ff.

8 The Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, November 30, 1878, page 351

9 ibid., page 351

10 This idea was brought to life in part at the 1900 exposition universelle, in the Vieux Paris section designed by the fantasy artist and writer Robida.

11 Reading through the various European descriptions of American culture present at the exposition, the reader begins to get a sensed of the emerging view of the United States as a country of great promise and barbaric excess. The bar, for example, with its profusion of exotic drinks — the "Brandy Smash" and "Mint Julip" — and raucous "superabundance of diabolic music — was the typical fairgoer's encounter with popular American culture at the 1878 exposition. See the "Impressions d'un Flaneur," published in L'Exposition Universelle de 1878, Journal Hebdomadaire, number 37, page 295.

12 The Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, August 24, pages 185-186

13 Report of the United States Commisssioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, 1878 (Washington, D.C., 1880), Vol. II, page 156

14 ibid.

15 Raymond Isay, Panorama des Expositions Universelles; Paris: Gallimard; pages 150-151

16 Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, Sept. 14, 1878, page 218

17 L'Exposition Universelle de Paris, Journal Hebdomadaire, Number 3, pages 23-24

18 Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition, October 5, page 263

In addition, as Daniel Boorstin writes in his The Americans: The Democratic Experience: "The general counsel to Western Union was so impressed by the brilliant electric arc lighting at the Paris Exposition of 1878 that when he returned to the United States, he persuaded Edison to explore its commercial possibilities."

19 The Chefs-d'Oeuvre d'Art, page 85

20 The Chefs-dOeuvre d'Art, page 86

21 For a full treatment of the story of this remarkable work and its passage from the 1878 exposition to the San Francisco Midwinter International exposition, and finally to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, see my essay, "The Doré Vase," in World's Fair, Volume III, Number 2, 1983; also L'Exposition Universelle de 1878, Journal Hebdomadaire, number 40, page 314-315.

22 Today, this magnificent work graces the central foyer of the Petit Palais in Paris.

22A For a comparison with a very similar work, executed at the same time but in a very different spirit, see Rodin's A Call to Arms

23 It should be noted that not all art critics were swept away by Mercié's paean. William Storey, the U.S. Fine Arts Commissioner, found the work "full of flutter, display, and excess of action, and is deficient in sobriety, simplicity, and that self-restraint essential to a great work in sculpture." (Report, II, p. 121)

24 The elephant, horse, and rhinoceros can be seen today outside the main entrance to the Orsay Museum. Across the terrace from these works are six statues from the 1878 exposition representing Europe, Asia, Africa, the Orient, North America and South America.

Statistical Appendix

Opening Date: May 1, 1878

Closing Date: October 31, 1878

Size of Site: 185 acres

Official Attendance: 16,032,000

Exhibitors: 52,835

Expenses: 55,775,000

Receipts: 24,250,000

Loss to Government: 31,000,000 francs (exact estimate vary)

Top Officials:

Jean Baptiste Krantz, Commissaire général

Charles Dietz-Monnin, Directeur de la Section française

George Berger, Directeur des Sections étrangères

M. le marquis de Chennevières, Directeur des Beaux-Arts

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Bergerat, É. Les Chefs-oeuvre d'art à l'Exposition Universelle, 1878 (Paris, 1878).

Bitard, A., editor. L'Exposition de Paris (1878), 40 issues in one volume (Paris, 1878).

Bouin, Philippe and Christian Chanut. Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositons Universelles (Paris, 1980)

Congress of Architects, Second International. Congrès internationale des architects, tenu à Paris, du 29 juillet au 3 aout 1878 (Paris 1881).

Glucq. L'album de l'Exposition: Vues intérieures et extérieures de Palais de l'Exposition (Paris, 1878).

Gonse, L. L'art ancien à l"Exposition de 1878 (Paris, 1879).

Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris Universal Exposition (London: 1878).

Illustrated Paris Universal Exposition (London, 1878); English version of L'Exposition Universelle de 1878, illustrée, May 7, 1878 through Novermber 30, 1878.

Isay, Raymond. Panorama des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1937).

Jouin, M.H. Notice Historique et analytique des peintures, sculptures, tapisseries, dessins, etc. exposés dans les galeries des portraits nationaux au Palais du Trocadero (Paris, 1879).

Krantz, Jean-Baptiste. Rapport administratif sur l'Exposition Universelle de 1878 (Paris, 1881)

Lamarre, C., and A. Frout de Fontpertius. Le Chine et le Japon à l'Exposition de 1878 (Paris, 1878).

Ministère de l'agriculture et du commerce. Monographie des palais et constructions diverses de l'Exposition universelle de 1878 exécutées par l'Administration,two volumes (Paris, 1882).

Norton, F.H. Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876, and of the Exposition universelle, Paris, 1878 (New York, 1879).

Ory, Pascal. Les Expositions Universelles de Paris (Paris, 1982).

Simon, Jules, general editor. Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1878, Paris. Rapports du Jury Internationale (Paris, 1880).

Society of Arts. Artisan Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1878 (London, 1879).

Strahan, Edward, editor. The Chefs-d'Oeuvre d'Art of the International Exhibition (Philadelphia, n.d.).

United States Commission. Report of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, 1878 (Washington, D.C., 1880).

ARTICLES

"Buildings and Arrangement of the Paris Exposition," Cassell's Magazine of the Arts, I, pp. 5, 29.

"Buildings of the Paris Exposition of 1878," American Architect, I, p. 357.

Chandler, Arthur. "The Poem of the Vine," World's Fair, Volume III, Number 2, p. 12.

— "Heroism in Defeat: The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1878," ibid., Volume VI, Number 4, p. 9.

Edwards, M.B. "Social Aspects of the Paris Exposition," Fraser's Magazine, XCVIII, p. 208.

"Exposition universelle de Paris en 1878; concours ouvert pour l'édification des batiments destinés à l'Exposition. Résultat du concours," Encyclopédie d'architecture, ser. 2, V (1876), p. 65.

Falke, H.J. von. "Art Industry in the Paris Exposition of 1878," Penn Monthly, X, p. 50.

"Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition of 1878," Cassell's Magazine of Art, II, p. 15.

Gindriez, C. "The Paris Exposition of 1878," International Review, V, p. 470.

"A Glance at the Paris Exposition of 1878," Victoria Magazine, XXXI, p. 139.

Godkin, E.L. "Politics of the Paris Exposition," Nation, XXVI, p. 337.

Hamerton, P.G. "American and English Painting at the Paris Exposition of 1878," International Review, VI, pp. 113, 547.

"Industrial Art at the Paris Exposition," Cassell's Magazine of Art, I, p. 66.

Knight, E.H. "Machinery at the Paris Exposition of 1878," Lippincott's Magazine, XXII, p. 755.

— "The Paris Exposition of 1878," ibid., p. 155.

Laugel, A. "The Paris Exposition," Nation, XXVII, p. 39.

Lejeune, L. "Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition, 1878," Lippincott's Magazine, XXII, p. 602.

McCormick, R.C. "American Success at the Paris Exposition," North American Review, CXXIX, p. 1.

Matthews, J.B. "The Paris Exposition of 1878," Nation, XXVII, p. 143.

Morison, G.S. "Machinery at the Paris Exposition of 1878," ibid., p. 237.

"The Paris Exposition of 1878" — anonymous articles published in:

— Appleton's Journal, XX, p. 66.

— Atlantic Monthly, XLII, p. 585, and XLIII, p. 41.

— Dublin Review, LXXXIV, p. 113.

"Pictures at the Paris Exposition of 1878," Atlantic Monthly, XLII, p. 707.

Royle, J.B. "The Paris Universal Exposition," British Almanac Companion 1876, p. 66.

Rudler and delmas. "Exposition universelle de 1878, étude sur les constructions du Palais du Champ de Mars," Encyclopédie d'architecture, ser. 2, VII, pp. 32, 62, 73, 93.

"Sculpture at the Paris Exposition," Cassell's Magazine of Art, III, p. 256.

Stillman, W.J. "Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition of 1878: American Painting," Nation, XXVII, p. 210.

Sturgis, R. "Ceramic Ware at the Paris Exposition," ibid., p. 269.

— "Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition," Scribner's Monthly, XVIII, p. 161.

— "Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition: American Painting," Nation, XXVII, p. 331.

— "Fine Arts at the Paris Exposition: French Painting," ibid., pp. 174, 222.

— "Floral Displays at the Paris Exposition," ibid., p. 191.

— "French and English House Furniture at the Paris Exposition," ibid., XXVIII, p. 46.

— "The Paris Exposition of 1878," ibid., XXVII, pp. 94, 112, 129.

— "Special Exhibition of the City of Paris," ibid., p. 253.

Thompson, S.P. "Artisan reports on the Paris Exposition," Nature, XXI, p. 397.

"The Universal Exhibition, 1878," Leisure Hour, XXVII, pp. 327, 335, 416.

Verney, Lady. "Paris During the Exposition of 1878," Contemporary Review, XXXII, p. 728.

Zola, Émile. "Lettres de Paris: l'Ecole française de peinture à l'Exposition de 1878," Le Messager de l'Europe, July, 1878.

Postscript

Rhino from the 1878 Exposition, now in front of the Orsay Museum

The author and the Rhino, some time in the 1980s