Expanded and Revised from World's Fair magazine, Volume VIII, Number 3, 1988

by

Arthur Chandler

POST-WAR PARIS

For many historians who look back more than half a century after the fact, the Roaring Twenties in Paris glow with a special magic. The war to end all wars had been fought and won. After almost fifty years of German occupation, the Alsace was once again a part of France. American soldiers lingered in Paris before returning home, and wrote to their friends that Paris was the place to be. Artists and intellectuals migrated to the "City of Light," finding there a freedom of existence and an exhilaration of thought unlike anywhere else in the world. "It's not so much what France gives you," said expatriate Gertrude Stein from her flat on the Rue de Fleurus, "It's what it doesn't take away." Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Aaron Copeland, Josephine Baker – the list of Americans in Paris in the 1920s and 30s is almost the history of American art and letters for those years.

For thoughtful Parisians, the presence of American writers and artists constituted further proof of what they felt to be the destiny of their city: to resume the mission civilisatrice, the cultural leadership of the entire world, as proclaimed by Victor Hugo half a century earlier. With the return of peace and prosperity, France could once again turn her thoughts to hosting an international exposition in order to reassert her position as the ruler of taste and style. But there was no groundswell of enthusiasm for launching an enterprise on the scale of the 1900 world's fair. Now, two decades later, France decided that it would be unwise and unnecessary to host another universal exposition. The 1900 fair, perhaps the most ambitious in all history, had properly inaugurated Paris as the city which set the themes for the coming century. What profit would there be in hosting a reprise? As Frederic Le Play had foretold in his report on the 1867 exposition, there was an irresistible pressure to make each fair more lavish than the previous one. The 1900 fair was certainly the most ambitious in the history of Paris; but it had lost money, and fell far short of the attendance figure that the commissioners had confidently predicted would eventuate.

Was Paris, then, to hold no more universal expositions? Would the leadership go to England, or Italy, or the United States? America seemed a likely candidate, having hosted major expositions in 1893, 1904, and 1915. Following the exhaustion of the First World War, it seemed likely that the leadership role would pass to the United States, which was undamaged physically and in form economically.

But the French were not ready to pass the flame to America. France would – France must – retain her leadership in this vital area. But future expositions in the capital city must have specific agendas. To hold another world’s fair, which exhibited everything from everywhere, was simply too vast an enterprise. The next French exposition should be organized around a particular theme – an idea proposed by Le Play in 1867 – and they should manifestly advance the interests of French business and government.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, France had a very definite idea as to what such a "theme exposition" should do. Looking back on the situation in France just before the war, Minister of Commerce Lucien Dior accurately saw his country's predicament:

French taste was law, and the effects of this were felt in both the public coffers and the private accounts of manufacturers, sellers, and artists. All this did not endure. Why? Because all around us, the English, Germans, Belgians, Italians, Scandinavians, and even the Americans themselves reacted, and sought to create for themselves – for better or worse – an original art, a novel style corresponding to the changing needs manifested by an international clientele. During this time, what did we do, apart from a few valiant efforts by an isolated few? Nothing, except to copy our own old-fashioned styles. The result? In 1912, people were talking of a "Commercial Sedan." [1]

So the agenda for the Exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels modernes was set: to show the world that French taste would once again lead the way in evolving a new international style. Just as French artists and craftsmen had set the standards for taste in the fine and decorative arts since the time of Louis XIV, so postwar Paris would show the world that France was willing and able to define the elements of the emerging style that would be known as Art Deco.

Edgar Brandt, Iron and Copper Screen called Oasis, exhibited at the 1925 Exposition in Paris

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

It is worth noting the change in nomenclature from "universal" to "international" in the official title of the exposition. The change itself bespeaks a pulling back from the larger aspirations of the earlier expositions. "Universal" meant both "all-inclusive" in the audience to which the exposition was directed, and "ranging over all forms of thought" in its exhibition of industrial and artistic products. The word "international" reveals a new perspective on the exposition. While national interests had always been present, overtly or covertly, at every exposition in Paris since 1798, nationalism now assumes the front rank, and replaces the urge for universality. And France, of course, saw herself as the orchestrator of international styles.

In many respects, Paris had never relinquished her role as leader. In painting, literature, and music, Paris had been the home of the avant-garde – the very term betrays its French origin – for decades. In women's fashion, it was still the Parisian hat, glove, and gown that set the standard for novel elegance in high society everywhere. Only in the decorative arts and architecture had the French resolutely clung to the past. The innovative art nouveau buildings and furniture of 1900 were forgotten. Old money and new alike preferred the tried and true styles – from the stately elegance of the ancien régime to the florid eclecticism of the Second Empire – for their own living spaces.

To some extent, though, Art Deco was a movement very much in the spirit of art nouveau. Both forms rejected the decorative vocabularies of the past, with their inevitable longings for classical motifs, themes, and proportions. Both were essentially surface arts, reflecting John Ruskin's earlier pronouncement that ornamentation is the principal part of architecture. But since the dawn of the twentieth century, there were three new influences that exerted themselves on the imagination of artists and craftsmen alike: Cubism in painting, colonial art from the French colonies, and the Bauhaus movement in architecture. Each of these influences could be seen clearly in the architecture and exhibits of the 1925 exposition.

Art nouveau had favored a kind of sinuous grace in its lines – the grace of draped vines, or of the languid movements of exotic dancers. The Cubism of Braque, Gris, and Picasso, though, heralded a new taste for abrupt angularity. Translated in to the decorative arts of furniture, clothing, and architecture, this abruptness was smoothed into a sleekness of line that we now call streamlined. "All that clearly distinguished the older ways of life was rigorously excluded from the exposition of 1925,"[2] wrote Waldemar George. The new style would be aggressively modern, taking its lead from the avant-garde in the other arts in expressing a new spirit of the age.

The art and artifacts of black Africa, collected by connoisseurs since the opening years of the century, were also seen as sources of a kind of primitive, muscular vitality that was unavailable either to the traditional decorative modes or to the languid lines of art nouveau. Many of the highly stylized and brilliantly colored fabric designs of Art Deco owe their existence to French designers' admiration for, and translation of, African fabrics and masks. The 1925 exposition marks a real turning point with regard to the French feeling towards the colonial peoples. African fabrics, once seen as quaint productions of a retarded people, were now energetically incorporated into the Art Deco style, which seemed to fit well with the angular energy of "primitive" art. Paralleling the fascination with African crafts and art was the mania for Josephine Baker and her Revue Nègre, which took Paris by storm in the 1920s. The enthusiasm with which the French embraced these two manifestations of black culture is, in one respect, a carryover of the thirst for the exotic that has marked French society for centuries. But, on higher level, the French acceptance of black culture marks a turning point in the acceptance of the society and mores of a people whom she once felt were backward and benighted. Art Deco is the clearest sign of a measure, not just of tolerance, but acceptance of the value of other cultures.

Poster for the Revue Nègre, Paris, 1925, by Paul Colin

The case of Art Deco in architecture is more complicated. The Bauhaus had been in business since 1919; but it was a German enterprise, and German aesthetics had little attraction for the French in the years following the Great War. Germany was not invited to participate in the 1925 exposition; and, as a consequence, Bauhaus ideas were present only as they appeared in other foreign pavilions – notably Melnikov's Russian pavilion and Le Corbusier's Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau. Though, as we shall see, there were some stunning attempts at the 1925 exposition to bring Art Deco to architecture, the results were, in the long run inconsequential – or, at least, not as far-reaching as its proponents hoped or believed. Art Deco in architecture was destined to become little more than a temporary fashion in interior decorating, or the addition of decorative flourishes to the facade. The International Style in architecture, which was to dominate the modern skyline for the rest of the century, grew out of Bauhaus principles, and rejected Art Deco as a superficial program out of keeping with "form follows function" and "less is more."

PLANS FOR THE EXPOSITION

The decorative arts exhibition, the government decided, would take place in 1914. But as discussions progressed, the date for the opening of the fair was pushed back to 1916, then 1917. The exigencies of the World War pushed the date back even farther, and it was not until 1921 that the funds were actually voted for the exposition. In addition, supporters of the Art Deco fair had to persuade the supporters of the colonial exposition to delay their opening, which was originally planned for 1924.

After much negotiation, Commissioner Dior persuaded the city of Paris to donate three million francs and seventy-two acres of land for the exposition. But best of all was the location of these acres. The Art Deco exposition would spread throughout the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais, Cours la Reine, the entire Pont Alexandre, and the Esplanade des Invalides. For the first time since 1855, the exhibition would hold forth in the very heart of the City of Light.

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

For the Art Deco fair, France erected nothing on the scale of the Eiffel Tower, and created no permanent legacy like the Grand Palais and Petit Palais from the 1900 exposition. Charles Plumet, chief architect for the exposition, was charged with conjuring up a splendid but temporary fairyland that would last for six months. Given the location of the fairgrounds, it was inconceivable that any imposing permanent structure could have been erected that would not have defaced the site. But knowing that their creations would vanish after the fair, architects could give free rein to their fancy.

In an exposition whose stated theme is the decorative arts, first impressions are supremely important. The imposing entranceway at the Porte d'Honneur, designed by the firm of Favier and Ventre provided visitors with a stunningly framed view of the Grand Palais. Simulated stone combined with bronze and wrought iron, illuminated by indirect neon light, to give the entranceway a sense of majesty by day, mystery by night. Cast-iron reliefs over the gateways celebrated the dignity of labor. American visitors passing through the Porte d'Honneur would be pleased to note La France, a monumental statue by Antoine Bourdelle, celebrating the arrival of American fighting forces in France in 1917.

"La France" by Antoine Bourdelle (original currently in the city of Briançon)

The Porte d'Honneur was only one of twelve monumental entraceways to the exposition. For some visitors, the most striking was the Porte d'Orsay, designed by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau. [3] The Art Deco steel structure served as a monumental frame for a semi-abstract mural. Figures and structures labeled Sculpture, Ceramics, The Book, Architecture, Wrought Iron, Furniture, and, highest-placed of all, Fashion. The ensemble clearly articulated the unity of the fine arts with the applied arts at the 1925 exposition.

Two views of the Porte d'Orsay, 1925

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

It is highly significant that the representation of the Eiffel Tower on the panel of the Porte d'Orsay is not placed with Architecture, but between Sculpture and Fashion. This explicitly symbolic placement gives us a hint as to the aesthetic sensibility of the Art Deco exposition. At the time when the Eiffel Tower was actually constructed, both advocates and opponents of the structure saw it as the bold (or brazen) representative of the aesthetics of engineering. The graceful sweep of the girders gave voice to the proud sense that engineers, too, had their own ideas of beauty. Thirty-six years later, though, Parisians saw the Tower as a venerable symbol of its age, a time when their parents and grandparents celebrated the centennial of the Revolution with a grandiloquent gesture in iron – a material long since replaced by steel as the technological building material of choice for all architects. Now, in 1925, the Eiffel Tower stood as a monument, like the Arc de Triomphe, whose form and function symbolized the fashions of a bygone age. By 1925, the Eiffel Tower had become a statement of fashion, a precursor of Art Deco.

THE ARTS OF LIVING

Once inside the gates, the visitor could sample the delights of Art Deco. Unlike the previous universal expositions, the 1925 exposition made no heavy intellectual or moral demands on the visitor. Peace and Progress, the twin themes of all the Parisian expositions universelles, might have been implicit in some of the individual works of art; but the fair itself was staged with the frank motive of re-establishing France as the arbiter of taste and fashion in the post-war world. In the past, said Lucien Dior, "French taste was law."[4] The goal of this exposition was not to promote the well-being of the human race, but to bring the aesthetic values of human race back under the hegemony of Paris.

It was the hope of the exposition organizers that the fair would bring about a truly new "modern" style. Paul Géraldy, writing for L'Illustration, noted that the term "modern" had been so widely and variously misappropriated by any and every group of artists that the word was falling out of favor. Part of the blame he placed on the small expositions that had taken place during the first decades of the twentieth century. There had been a Franco-Belgian exposition of fashion in 1922, a Spanish exposition of furniture and interior Decoration in 1923, an ambitious French show of high fashion and luxury products in New York in 1924 – plus a host of even smaller events which Géraldy felt were only confusing the attempt to define a truly modern style:

Poster for the Franco-Belgian Exposition, Brussels, 1922

The effect of these little expositions, for about the last twenty years, has been to present us with a confused picture: so many bizarre attempts, so many extravagant ensembles, so much absurd furniture, so much outrageous Decor, that the public could make but little sense out of the disorder. [5]

The Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes was supposed to bring together the nations of the world and to show, if not quite a unified front, at least some sense of a developing common aesthetic among the practitioners of decorative art and architecture. However, many nations chose not to participate. The United States, Canada, Mexico, all of Central and South America, were absent.[6] Germany, of course, was not invited. For many nations, the prospect of devoting so much effort and expense in the wake of a world war must have seemed frivolous. But for those nations that did choose to participate, the exposition could be viewed as an attempt to find some common ground of unity after the tragic and divisive war.

THE LEFT BANK

It was on the left bank – the student quarter, the Bohemian section, the old military school and the Eiffel Tower – that France elected to raise her exhibits for the world to behold. At the Place des Invalides, the Ambassade de France exhibited in a single structure the kinds of unification of art and decoration that set the theme for the entire fair. Some twenty-five rooms flanked a three-sided courtyard. Each of the rooms had its proper theme, and was designed, furnished, and decorated by the leading artists and artisans of France. There was a room for "Monsieur," a room for "Madame," a working office-library, and a special chamber for music. Each space was crowded with works of art and craft to delight the eye. All the decor was in the modern mode, with little or no reference to past styles. In the Ambassade, the French government gave its official version of the domestic future: spacious, functional, and adorned with the very latest fashion.

Office in the Ambassade (gouache and pencil by Pierre Chareau, 1925)

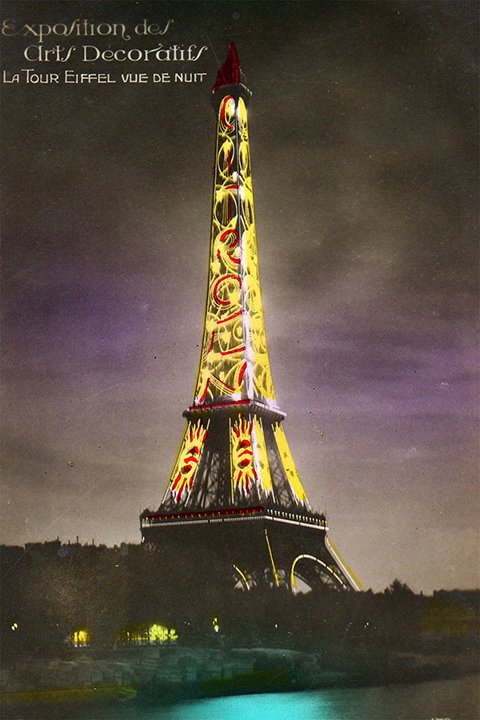

Looking north-westward, the visitor could see the Eiffel Tower, bedecked with lighting provided by Citroen, whose name was emblazoned in lights on the iron beams of the tower for the duration of the exposition:.

Gazing across the courtyard toward the Seine, the visitor could admire the much smaller glass fountain tower designed by Lalique. In two glances, the visitor could encompass the different spirits of 1889 and 1925. The one tower, rising three hundred meters over the Champ de Mars, represented the triumph of modern engineering over the traditional architecture of decoration. Over 140 figures encrusted Lalique's 14 meter tower of crystal that shimmered as the light struck the waters cascading over its sides. In 1889, the power of unadorned iron; in 1925, the poetry of decorated crystal.

The Lalique Fountain at Night

At the opposite end of the right bank quadrangle the visitor encountered a series of exhibits by the four major Parisian department stores. Such stores had been in existence for nearly three-quarters of a century; and, indeed, their existence owed something to the official encouragement of such enterprises by the first exposition universelle of 1855. The original department stores, however, stressed that their mission was to provide good quality goods at a price affordable to the masses. The department store exhibits at the Art Deco fair paid little attention to the bon marché ideals of the earlier expositions.

The shape of each of the four buildings was highly original, and designed to attract maximum attention while still staying within the bounds of good taste. But with the abandonment of the traditional architectural vocabulary, such bounds were difficult to distinguish. The Studium Louvre by Laprade seemed like an updated and octagonal version of Bramante's Tempietto in Rome. On the lower floor, mannequins in the bay windows gave the visitor a preview of the high fashion displays within. The second story featured a setback porch with lush greenery flowing around a series of monumental vases that overflowed with ceramic flowers.

Laprade's Studium Louvre

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

The Louvre store chose the elegance of octagonal form. Henri Sauvage, the architect of the Primavera pavilion, designed a building that drew its inspiration from African thatched huts:

The Primavera Pavilion (Click the image for a lightbox view)

The Bon Marché structure, designed by Louis-Hyppolite Boileau, was purest Art Deco, with rectangular and curved geometric forms blending in a graceful ensemble.

The most daring of the four stores, however, was the Galleries Lafayette (Hiriart, Tribout, and Beau, architects). The Art Deco facade and interior were faced in a richly textured marble. A bold, flaring sunburst design greeted visitors as they passed into the interior. Inside, the theme of the major exhibit was "la vie en rose": a display of the boudoir of the tasteful and wealthy woman of fashion in the 1920s who knew how to coordinate the angular lines of Art Deco with a sense of stylish grace. The furnishings were in rose hues, offset with silver and black marble. In every respect, the furnishings reflected the ideas of Maurice Dufrene, director of the Lafayette studios:

Hiriart, Tribout, and Beau: Galeries Lafayette

A cabinet maker is an architect. . . In designing a piece of furniture, it is essential to study conscientiously the balance of volume, the silhouette and the proportion in accordance with the chosen material and the technique imposed by this material. [7]

Dufrene is expressing the same ideals that had been enunciated by avant-garde artists and architects for over a decade: the ideas and style of the past are outmoded. Let the nature of the material and the sensitivity of the artist dictate form. In addition, the supposedly inferior works of craftsmanship – products of the artisan as well as those of the artiste – are of equal stature to the "high art" of architecture. Craftspeople, too, have their high aesthetic standards, which are every bit as rigorous and important, in the overall scheme of things, as the work of the architect.

It is the Marseillaise of modern art.

THE RIGHT BANK: FOREIGN NATIONS

To the visitor entering the fairgrounds through the Porte d'Honneur, it must have been immediately apparent that national differences and political agendas had triumphed over any international spirit of solidarity among decorative artists. The British pavilion, designed by Easton and Robertson, was indeed a tasteful and forceful example of the Art Deco style. But inside the building, when visitors came to inspect the display of photographs showing current architecture in Great Britain, they found that the English were erecting buildings in quite traditional styles.

Close by the British pavilion, in a place of honor among the nations on the Right Bank, was the Italian pavilion. Mussolini, whose gigantic features in bronze dominated the interior of the pavilion, had decreed that Italian fascism was the reborn descendant of the Roman Empire. The Italian building, accordingly, should announce that resurrection. As seen by two English visitors, the Italian structure was "a monumental horror of illiterate classicism with marble columns and gilded brickwork that would have disgraced Caligula." [8]

The Italian Pavilion; Armando Brasini, architect

Italy, however, was only attempting what almost all the other pavilions, save one, tried to accomplish: the making of a national pavilion that was explicitly symbolic of the nation that it housed. In the Netherlands building, the effect of this kind of confident nationalism was almost comic. The Dutch had used good honest traditional brick to erect what looked like an inverted tulip athwart interlocking planes in the Mondrian style. At the base of this tulip were stylized waves, and a little brick schooner plows the waves over the word "Hollande," which stands out from the planes in sharp relief. Inside, de stijl furniture, in the manner of Rietveldt and Wouda, pointed towards the kind of abstract furniture design favored by the Bauhaus school and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Holland Pavilion; Jan Frederik Staal, architect

Most of the national pavilions denied, in their regional shapes and themes, the very internationalism that the exposition was trying to promote. The results were sometime sober (England) pugnacious (Italy), or ever rollicking (the Netherlands). But the overall effect was the same: a proliferation of regional styles, but nothing that suggested the emergence of a style for all humanity. The great classical traditions that had held together public architecture since the Renaissance were gone. "Away with the architraves, pillars, and antiquated temples of the aristocratic past," these national pavilions seem to say. "The universal human community will produce its own style, appropriate for its own age, here in the twentieth century!"

It was the Russian building, however, that most accurately forecast the future. The Revolution of 1917 and the announced mission to lead the world into the classless society of the future gave the Russian architect Konstantin Melnikov a moral reason to reject both the classical and regional architectural traditions. The resulting building forecast the international style that would not emerge fully for two decades: regular glass rectangles set into unadorned horizontal and vertical supports. Inside, the sparse decor emphasized worker solidarity. Peasant art was on display as a sign of eternal rural vigor in the Russian landscape. But it was Rodtchenko's workers' club that showed the vision of the urban future for Russia: hard, geometric chairs without cushions facing a common table designed to hold magazines and pamphlets. On the walls are posters proclaiming the good of the Soviet Republic, and racks of periodicals for workers to read. The Soviet pavilion announced clearly that the Russian view of corporate life in the twentieth century that would eventually, inevitably, capture the higher echelons of political and economic power in the world.

Konstatin Melnikov, Soviet Pavilion, 1925

Workers' Club, Soviet Pavilion

THE RIGHT BANK: FRANCE

The visitor might make the transition between the foreign pavilions and the French exhibits on the right bank by stopping in at the Pavilion of Tourism. Here the tourist to the exposition could go to change currency or make boat and train reservations for travel away from Paris. This pavilion, which would be repeated and expanded in the 1937 exposition, was the first explicit acknowledgement by the French government that tourism was a proper concern of the nation. After all, was not an international exposition a kind of condensed tourism, an opportunity for the visitor to Paris to see the highlights of world culture?

Interior of the Tourism Pavilion; Robert Mallet-Stevens, architect

The city of Paris herself chose to present two sides of her many-faced nature: education and taste. All the major exhibits in the Pavilion de la Ville de Paris were mounted by students from the schools of Paris. Boys and girls, from ages four through nineteen, made furniture, bound books, wove tapestries, and placed all their handiwork around an elaborate scale model of a city. The exhibit was universally praised as a splendid fulfillment of the long-stated ideals of French trade education: to provide all young people with both the skills to make useful objects and the aesthetic sense to make those objects pleasing to look upon.

Stretching westward along the Right bank of the Seine were the exhibits devoted to French colonies – including the special prize and pride of France: Alsace. Of all the regions of France which exhibited it was the Alsace section that captured the special joy of the French. This half-French, half-German region had been appropriated by Germany as one of the most coveted spoils of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. France had bitterly resented the loss; and it was common knowledge that she would have traded all her African and Asian colonies for the return of the Alsace. After the defeat of the Germans in 1918, France received her beloved Alsace back into the fold – and acquired some new colonies abroad as well. Northern Africa, Western Africa, Indochina, Morocco, Tunisia – all received a pavilion, and all were given a chance to display their contributions to the decorative arts theme of the exposition. But Alsace was granted three buildings, each one showing a different aspect of life in the regained French province.

Bedchamber in La Maison d'Alsace

THE NEW SPIRIT

There can be no international exposition in Paris, it seems, without at least one dissident artist exhibiting in defiance of the authorities and official sanction. In 1855, it was Gustave Courbet who defied the juries by setting up his own gallery in plain view of the official exhibition of art. In 1867, it was Manet; in 1878, de Neuville and the military school of painting; in 1889, Gauguin; in 1900 (but with partial blessings of the city of Paris), Rodin. In 1925, it was Le Corbusier whose pavilion outraged the sensibilities of the authorities, and set in motion a debate about modern architecture that has continued in Paris to this day.

Le Corbusier had troubles with the exposition authorities from the start. After strenuous petitioning for exhibit space, he was finally granted one of the worst sites of the fair. Here Le Corbusier and his associates erected the Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau, and announced that this spirit's program was "to deny decorative art, and to affirm that architecture extends to even the most humble piece of furniture, to the streets, to the city, and to all." [9] The house of the future, he continues, must be a machine à habiter, a "machine for living," and not a three-dimensional backdrop for interior decorators.

As exposition authorities laid eyes on Le Corbusier's cellule, they were horrified. The uncompromising geometry of the exterior was carried out mercilessly through the interior. A slab of stone cantilevered out over the living room, forming a kind of interior balcony. Boxlike furniture faced Juan Gris paintings on the wall, and stark Jacques Lipchitz sculptures adorned the otherwise Spartan Decor. Art Deco was nowhere to be seen. In its place was Le Corbusier’s uncompromising vision of modernism: less playful, more severe, more demanding in its adherence to the dominating presence of pure Form.

Interior of Le Corbusier's Pavilion de l'Esprit Nouveau

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

But the crowning audacity lay beneath the glass of the exhibit tables that Le Corbusier had placed strategically in the other part of his exhibit. Here, in his Plan Voisin de Paris, the upstart architect proposed the demolition of vast sections of Paris – especially the second, third, ninth and tenth arrondissements – and replaced these historic sections with Le Corbusier high-rise complexes on a grand scale. Each of the projected facilities would hold three thousand people, and free them spatially from the dead hand of the past.

Mark Tuttle, Animation (2009) of Le Corbusier's Plan Voisin

Most of French architectural authorities were incensed at this brazen attempt to destroy the history and character of Paris. To begin with, they ordered a 20-foot high fence to be erected around the entire Esprit Nouveau pavilion, in hopes of hiding the shameful spectacle from curious visitors. The French Minister of Fine Arts, however, had the fence removed. The international jury was astonished, but proposed to award the audacity with a first prize. The French Academy, annoyed that the fence had been removed, had its revenge by vetoing the international jury's vote. The end result was for Le Corbusier what every avant-garde French artist most desires: a succès de scandale. From that time forward, his reputation as a leading architect was confirmed, and Le Corbusier never wanted for commissions.

AFTERMATH

Was the Art Deco exposition a success? If the main point was to show that a new decorative style could be formed without reliance on tradition, the exposition achieved its goal. Countless talents from many countries showed what could be done without turning to the Greco-Roman tradition in art and craft. The Art Deco style was born; and, though America did not participate directly in the fair, the influence of this style would be strongly felt across the country for the next 20 years. The Treasure Island Fair, held in San Francisco in 1939-40, embodied America's own version of the 1925 Paris Exposition. In an important sense, the battle begun with Eiffel concluded: modern themes and modern methods and materials could and should generate their own style, symbolizing a twentieth-century world view.

But there was a contradiction inherent in the Art Deco style, a kind of duality that in no sense owed its lineage to Eiffel: the opposition of structure and surface. The Art Deco style of 1925 concentrated on the surface of things. As Marie Dormoy pointed out:

"In 1900, we saw the triumph of noodling ornamentation. Today we have the pretense of doing away with such ornament – but it is only a pretense. We no longer speak of ‘the right line, or ‘the essential thing’ or of construction. Instead, to take the matter as it really is, today the ornament has become the essential thing, with the result that we have more useless ornament than ever before.”[10]

The same motifs appear again and again in contemporary commentaries: art deco is superficial, and merely replaces one decorative vocabulary with another. "The faith in decorative art gives the lie to the spirit of the entire exposition,"[11] wrote Waldemar George. August Perret remarked, "I would like to know who first stuck together the two words ‘art’ and ‘decorative.’ It is a monstrosity. Where there is true art, there is no need for decoration." [12] Only in Le Corbusier's Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau and Melnikov Soviet pavilion were the tendencies toward an international style in architecture brought out to the fullest. In these two pavilions, decoration was rigorously subdued or eliminated.

Then there was the whole question of Art Deco as an international style. The French had hoped that, in drawing the world to Paris for the exposition, France would emerge from her "commercial Sedan" as the leader in the new style of architecture, interior design, and fashion. But all the buildings (except for those of Le Corbusier and Melnikov) and their contents were intensely regional or national in their approach to decorative art. It was clear that no matter how clever or tasteful the work of French artists, each country would go its own way with the Art Deco style. France would be a participant, but not a leader.

It remained for the Russians to give the world the final, defiant gesture of internationalism in the face of Art Deco. At the closing ceremonies of the exhibition in October, 1925, Russia's flag stood with all the rest atop the poles surrounding the speaker's platform. Slowly, solemnly, the flags were lowered together, signifying the official end of the exposition. But as the banners were lowered, one remained, triumphantly waving above the rest. The Russians had refused to lower their flag. "We alone carry on the revolutionary spirit," asserts this gesture. The audience and officials were outraged. But what could they do? The hammer and sickle remained aloft as the crowds drifted away back into the summer streets of Paris. Only much later, after the exposition officially closed its doors, did the Russians lower their flag in triumph.

NOTES

1 Quoted in Bouin and Chanut, Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1980), page 170. The Battle of Sedan, in 1870, was the decisive defeat of the French Army by General von Moltke – the defeat that led to the downfall of the Second Empire and the occupation of Paris by German Troops.

2 L’Amour de l’Art, " "L’Exposition des Arts décoratifs et Industriels de 1925, les tendences générales," p. 286

3 Later, Boileau was chosen to be one of the architects of the Chaillot Palace for the 1937 exposition.

4 Bouin and Chanut, page 170

5 Paul Géraldy, "L'Architecture Vivante," in L'Illustration, June, 1925, n.p.

6 It is interesting to note that the space originally reserved for the United States was subsequently given to Japan

7 Quoted in Frank Scarlett and Marjorie Townley, Arts Décoratifs: A Personal Recollection of the Paris Exhibition (London, 1975) page 78

8 Quoted in Scarlett and Townley, page 46

9 Le Corbusier, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret: oeuvre complète, 1910-1929 (Zurich, 1960)

10 Marie Dormoy, "Interview d’August Perret sur l’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs," in L’Amour de l’Art, May, 1925, page 174

11 George, Waldemar. "L'Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et industriels de 1925 – les tendences Générales," in L'Amour de l'Art (Paris, 1925), page 283

12 Marie Dormoy, op. cit., page 174

STATISTICS

Opening Date: April 25, 1925

Closing Date: October 25, 1925

Size of Site: 72 acres

Official Paid Attendance: 15,019,000

Exhibitors: 15,000+

Expenses (estimated): 80,480,000 francs

Receipts (estimated): 95,180,000 francs

Profit to Government (estimated): 14,700,000 francs

Top Officials: Fernand David, Commissioner General

Paul Léon, Director of Fine Arts

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Encyclopédie des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes au XXème siècle en douze volumes (Paris, 1928, 12 volumes)

George, Waldemar. L’Amour de l’Art (Paris, 1925)

Géraldy, Paul. L’Atrchitecture Vivante," in L'Illustration, June, 1925

Paris, W. Francklyn. "The International Exposition of Modern Industrial Art in Paris," in Architectural Record, September and October, 1925

Rambosson, Yvanhoé. "L’Evolution de l’art moderne," in L'Illustration, June, 1925

Roux-Spitz, M. Exposition des arts décoratifs, Paris, 1925: Bâtiments et Jardins (Paris, 1925)

Scarlett, Frank andTownley, Marjorie. Arts Décoratifs: A Personal Recollection of the Paris Exhibition (London, 1975)

Here is my account of the historical background for the Paris expositions